VO2 max is one of the key performance metrics in cycling, and we’ve found a full-time solicitor (the reigning men's British Hill Climb Champion, no less) with an aerobic engine large enough to compete at the Tour de France.

BikeRadar’s Jack Luke and Joe Norledge have been collaborating with Andrew Feather as part of our Hill Climb Diaries series. Last week, in a bid to find out exactly how good Andrew is, we took him to the University of Bath’s Human Performance Laboratory to get tested.

What makes a National Hill Climb champion?

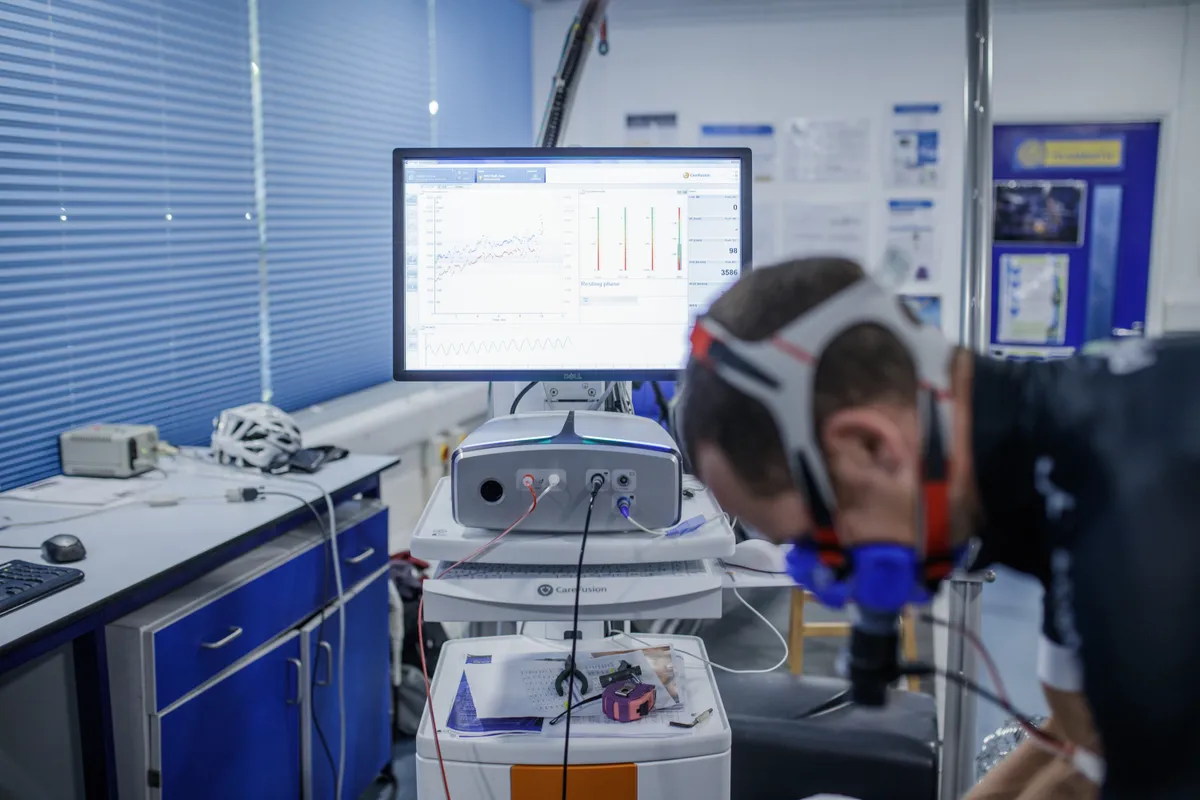

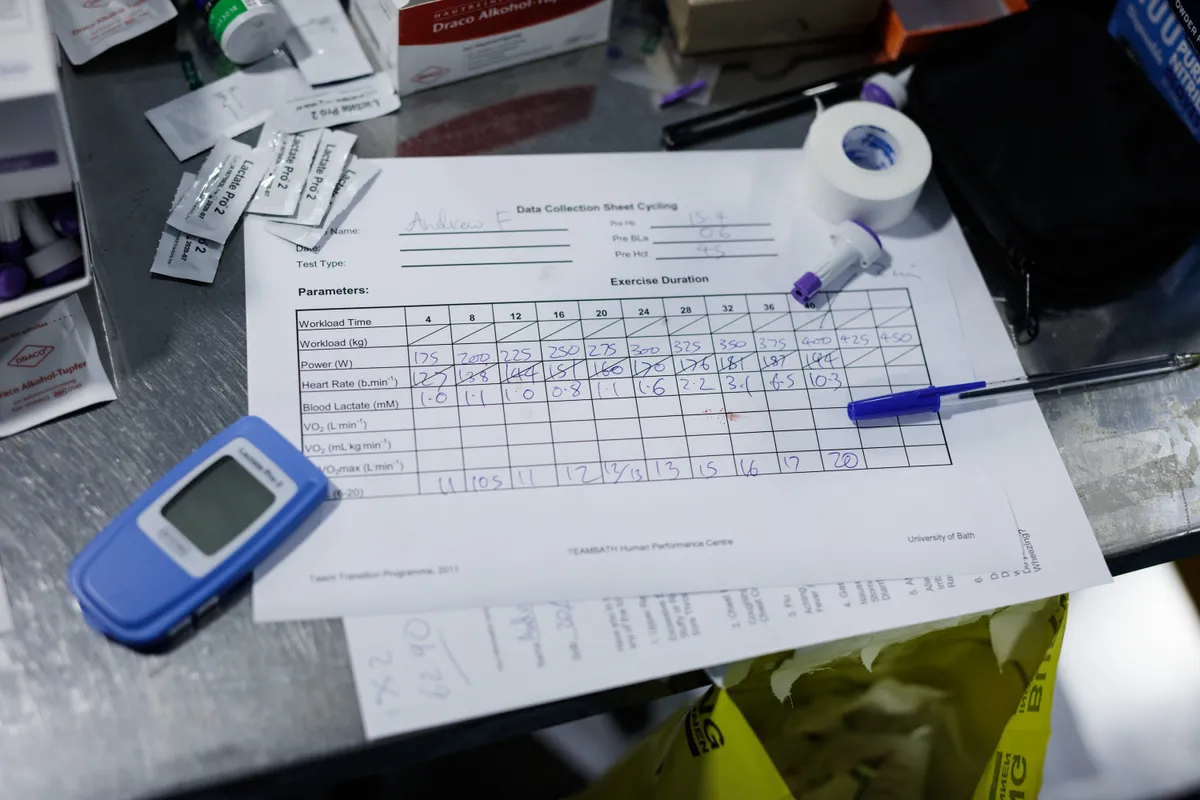

Jonathan Robinson, the university’s Lead Applied Exercise Physiologist, explained the procedure to us: Andrew, a former elite-level road racer turned hill climb specialist, would ride an SRM Ergometer stationary bike with the resistance ramping up by 25 watts every three minutes, until exhaustion.

He would wear a mask that measures — via an innocuous-looking machine attached to a computer — the oxygen and carbon dioxide levels in each breath. The largest number achieved during the test for millilitres of oxygen consumed per minute would be his VO2 max.

VO2 max is the maximum volume of oxygen your body can use in a minute, usually expressed relative to body weight. In more general terms, it describes the size of your aerobic engine.

Every three minutes, Jonathan would also prick one of Andrew’s fingers with a needle, take a blood sample to measure his lactate levels, and make a note of his heart rate.

This information would be useful for setting Andrew’s training zones accurately and tracking changes in fitness if he were to perform the test again.

Before all that fun began though, Jonathan measured Andrew’s height, weight and body fat percentage.

- Height: 175cm

- Weight: 62.9kg

- Body fat: 5.8%

That last figure might seem minuscule, but bear in mind that it’s currently hill climb season, so Andrew is at his optimum race weight.

The test started at 175 watts. That’s easy for Andrew, but it’s higher than normal. If the test had started from zero it would have taken an eternity.

Increasing the starting resistance simply shortens the time to exhaustion, so it’s set according to an easy pace for the individual athlete.

But after almost half an hour of pressing progressively harder on the pedals, Andrew hit his ceiling at a brutal 425 watts.

For comparison, Jack and Joe topped out at 325 and 375 watts respectively when they performed this test a few months ago.

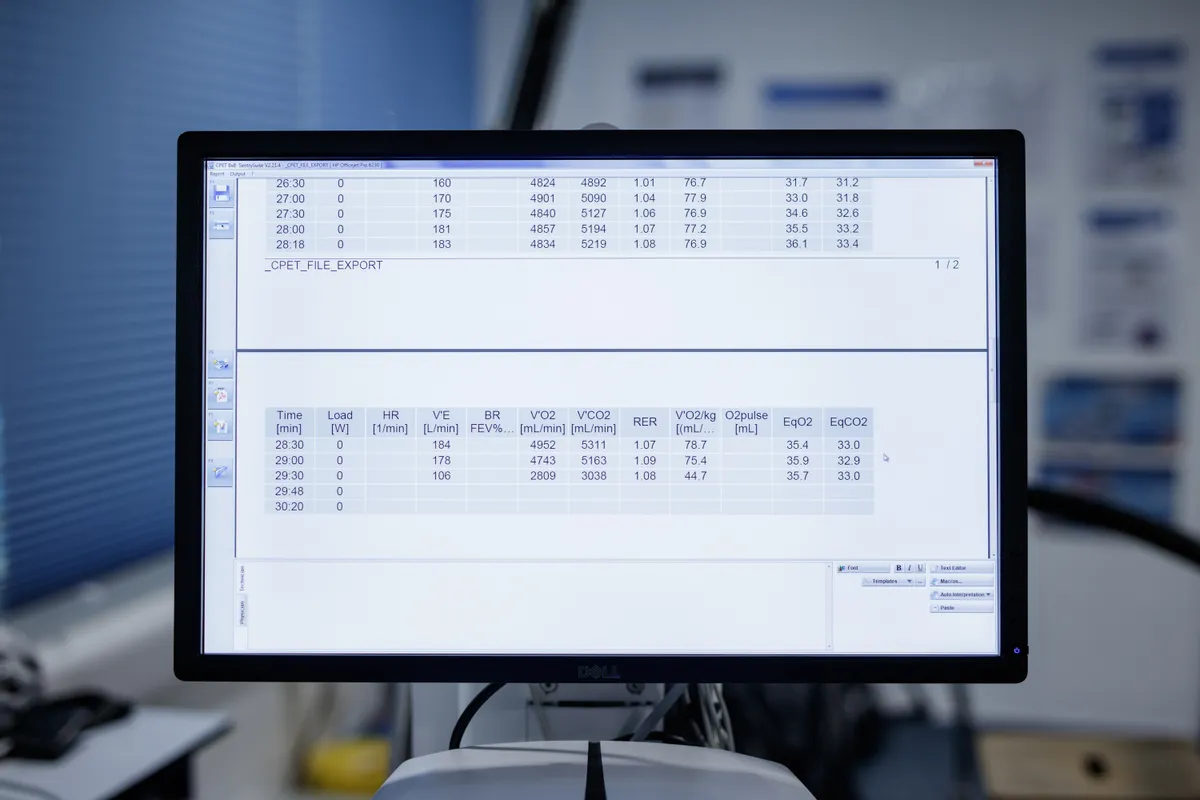

Jonathan removed the mask from Andrew’s face and gave him a moment to recover. Having reached a maximum heart rate of 194bpm, Andrew was nailed. But in the end, it had been a controlled effort.

Andrew pushed himself to exhaustion without fighting the bike or his pedalling technique falling apart.

Andrew had hit a peak oxygen consumption of 4,952ml/min. That translates to a VO2 max of 78.7ml/min/kg, which is exceptional.

When Jonathan read it out, there was an audible gasp from the small group of staff and students in the lab — it was one of the highest scores they'd ever seen on the bike in the lab.

The lactate concentration results showed that, for Andrew, his Onset Blood Lactate Accumulation (OBLA) – his one hour time-trial power or FTP – was around 350 watts (5.56w/kg). His Lactate Threshold (LT) – his all-day riding power – was a mind-boggling 300 watts (4.76w/kg).

Research by the University of Bath, published in 2012, suggests that most participants in the Tour de France have VO2 max scores ranging from 70 to 80ml/min/kg. General classification winners push in to the 80s. For the general population, 50 is considered an excellent score. On paper, Andrew is up there with the very best.

What next?

Once Andrew had digested the news that he was objectively brilliant, he had a few questions for Jonathan. Could he have tried harder? How could he beat his score and hit 80ml/min/kg? And how could he apply these results to his training and racing?

The answer to the first question is, in short, no. The test periodically ramped Andrew’s breathing and heart rate up until he surpassed the highest amount of oxygen his body could use. Your underlying physiological limit isn’t affected by effort.

The other questions are more complex and require exposing Andrew’s relative weaknesses and how he can adapt his training regime with the aim of pushing his VO2 max beyond 80.

If, for example, Andrew could lose 1kg and maintain his current aerobic ability, he should see his VO2 max score increase to 80ml/min/kg. At 5.8 per cent body fat, however, it’s difficult to see where that kilo could come from.

Then, of course, there are all the other components to going fast on a bike outside of the lab.

How efficiently can his body convert that oxygen into power? What percentage of his VO2 max is sustainable and for how long? How responsive is Andrew’s body to training? And that’s before we even get to motivation, bikes, aerodynamics, nutrition, etc. It’s a rather large can of worms.

We already knew Andrew was special — he’s a national champion after all — so these tests invariably throw up more questions than they answer. But they are also a fascinating insight into the physiological prowess of a national champion, and one who trains and races while holding down a full-time job.

What matters, of course, are results on the road, and Andrew looks on track to defend his title at the 2019 RTTC National Hill Climb Championships in Haytor later this month (27 October), where, incidentally, he took the Strava KOM this week on a recce ride.

Andrew Feather’s key stats

- Age: 33

- Height: 175cm

- Weight: 62.9kg

- Body fat %: 5.8

- Peak power output in test: 425 watts (6.75w/kg)

- VO2 max: 78.7ml/min/kg

- OBLA: 350 watts (5.56w/kg)

- LT: 300 watts (4.76w/kg)

- Max heart rate: 194 bpm

- Peak lactate: 10.3 mmol