Yeti has gone big on 29ers recently, with its much-lauded SB100, SB130 and SB150 covering the full gamut for those who want big wheels from cross-country to enduro. But the Colorado company has just launched its first 27.5in-wheeled bike for some time: the SB165.

According to Yeti, it sees the big-wheeled bikes as its race-focused options, whereas the SB165 is aimed more at what it calls “ripping”. Basically, this means having fun on a bike: jumping, hucking, carving berms and – dare I say it – jibbing. It’s designed to be in its element in the bike park or bombing down technical terrain, whether you have an uplift or not.

To that end, it’s got (you guessed it) 165mm of rear suspension. All models are equipped with coil shocks and a 180mm-travel fork. The frame has been tested to what Yeti calls “downhill standards” for head tube strength, and the head angle is Yeti’s slackest at 63.5 degrees.

But when I rode the SB165 in Slovenia last month I found it to be far more versatile and pedal-friendly than the above description might lead you to believe. Read on to find out how it rides.

Yeti SB165 frame details

As you’d expect, Yeti’s Switch Infinity suspension system, which features a main pivot that moves up and then down on a pair of vertical rails as the suspension compresses, is present and correct.

Unlike Yeti’s other bikes, it’s been tuned for coil shocks, but it shares the same Switch-Infinity hardware, as well as linkage bearings and axles, with all of Yeti’s other full-suspension bikes, save for the SB100. That should help with finding spares should you need to.

The cable routing is particularly neat and completely internally guided so, according to Yeti, when you push a cable in one end it should simply slide out the other.

The frame has room for up to 2.6in tyres (as does the fork) and there’s room inside the frame for a standard 550ml water bottle.

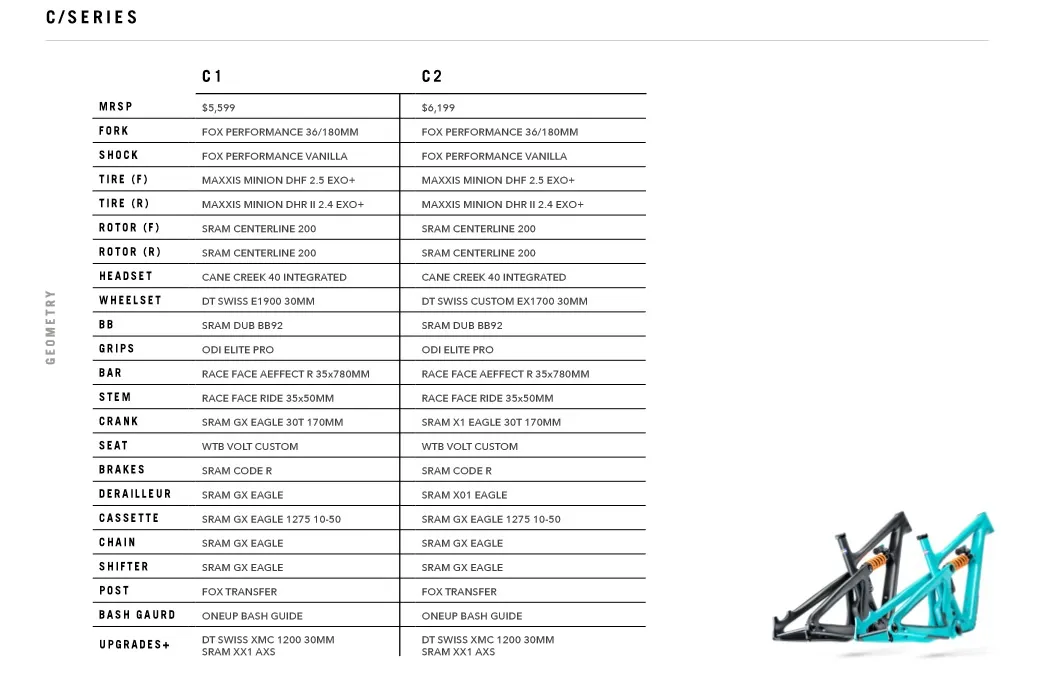

There are two frame material options: carbon or carbon. The Turq series carbon fibre is the top-end material (which we’ve ridden), while the C series is lower-grade carbon fibre which, according to Yeti, has similar stiffness properties but weighs 220–250g more.

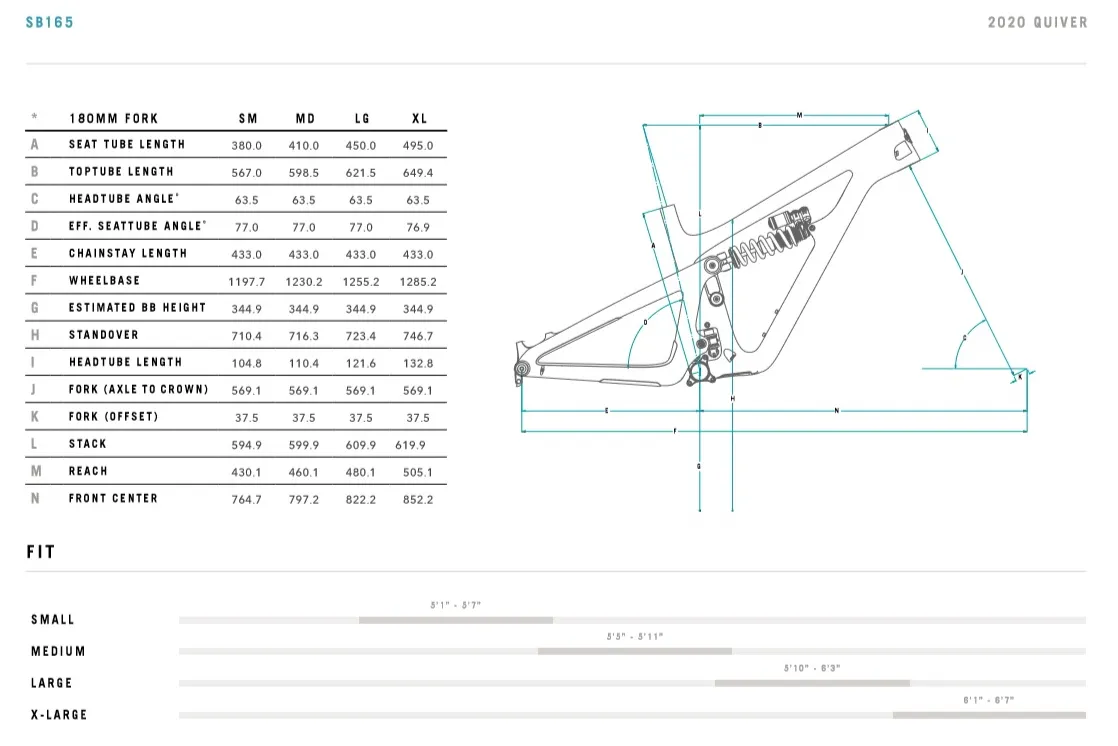

Yeti SB165 geometry

The standout figure on the SB165 is a downhill-bike worthy 63.5-degree head angle. That’s combined with a short-offset (37mm) fork which increases the trail figure, thereby making the steering feel even more settled and slow when descending than most DH bikes, which typically use longer fork offset.

Equally important is the steep, 77-degree, effective seat tube angle, which puts your hips nicely over the pedals when climbing. The reach is long too – 505ml in XL (tested) or 460ml in a Medium. Interestingly, this is combined with a 50mm stem, which is on the long side by cutting-edge geometry standards.

I measured the bottom bracket height, wheelbase and chainstay length on my XL bike. Encouragingly, my measurements agreed with those in the below table – that’s not often the case when comparing spec sheet geometry to real-world measurements.

What the spec sheet doesn’t tell you is the weight. My XL test bike, fitted with a 500lb per inch spring, weighs 14.8kg / 32.6lbs without pedals — and that's according to my own trusty scales.

Yeti SB165 suspension

To make the SB165 play nicely with coil shocks, the suspension linkage is considerably more progressive than previous Yetis. In other words, the leverage ratio between the rear axle and the shock decrease as it gets deeper into its travel, thereby making the suspension firmer towards the end.

This can be quantified by the percentage progressivity, which compares the leverage ratio at sag with the ratio at the bottom out.

The SB165 has 27.5 percent progressivity, so it’s 27.5 percent firmer at the end of the stroke than a linear bike with a constant leverage ratio. Compare that to the more air-shock-focussed Yeti SB150, which has around 15 percent progressivity.

The main advantage of Yeti’s Switch Infinity system is that it allows its designers to control the anti-squat (how much the chain tension is used to prevent the suspension compressing due to pedalling forces) throughout the stroke.

Yeti uses this to provide a generous amount of anti-squat (around 120 percent) near the sag point, so the suspension stays high in its travel and doesn’t bob much when pedalling. Yet, after sag, the main pivot switches from rising to falling on its rails and this helps the anti-squat to rapidly decrease after the pedalling-zone, so the associated pedal-kickback is minimised later in the travel.

This article explains the topic of suspension linkages in far more detail

The 165mm of vertical rear-wheel travel may sound imbalanced against the 180mm-travel fork, but because the fork delivers its 180mm of travel at a jaunty angle parallel to the head angle (63.5 degrees), the vertical component of its travel is similar to the rear.

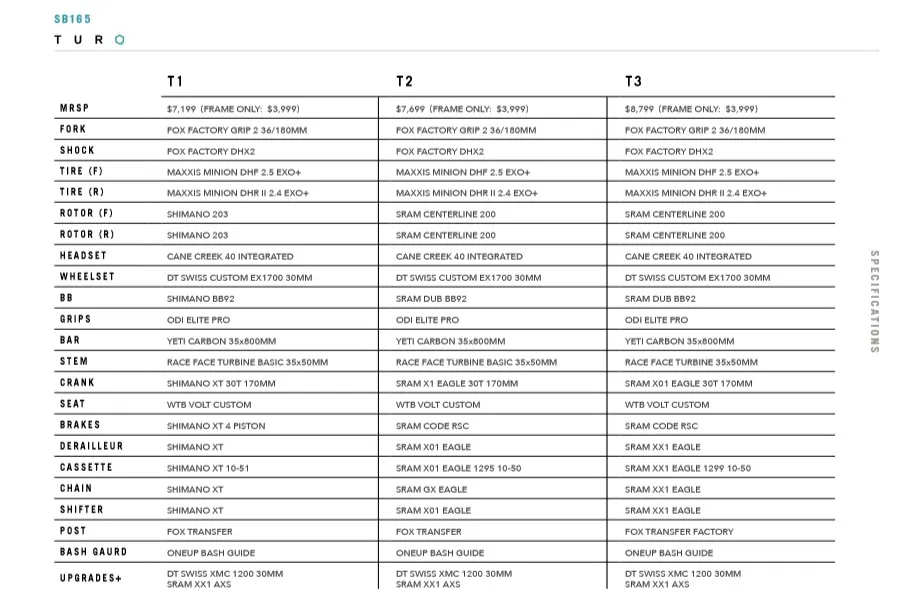

Yeti SB165 parts and prices

There will be three spec levels available on the more expensive Turq frame, the cheapest of which utilises Shimano’s new XT drivetrain and brakes, and two spec options for the more affordable C frame.

One thing you won’t find is a women’s specific version. Yeti has completely ditched its line of female-specific “Beti” bikes, apparently due to an internal call from Yeti’s female employees that they simply weren’t needed. According to Yeti’s president, Chris Conroy, the Beti range made up around 10 percent of sales, and he says they would have kept the range going if Yeti staff felt the range offered a real benefit to female riders.

It’s nice to see ONEUP’s excellent bash guides installed throughout the range. We’re also fans of the SRAM Code RSC brakes and ODI Elite Pro grips.

Maxxis EXO Plus tyres are slightly more resilient than their standard EXO casing, but this bike would be better suited to the thicker DoubleDown casing in my opinion.

The charts below provide the full parts list.

Yeti SB165 pricing

We currently have pricing information for the below models:

£7,299 / €8,190 / $7,599

Array

Yeti SB165 first ride impressions

I rode the SB165 Turq T2 (£7,699 / €8,690 / $7,999) for one day on the Slovenia/Italy boarder. The trails had a good mix of high-speed ruts, rocky chutes and sudden awkward climbs. The ride started with a long climb on rough fire road and some singletrack. These trails were unfamiliar to me though, so I’ll keep this brief.

Before I started riding I set the bar height to its maximum setting. At 190cm tall I prefer a high bar height, and the longer a bike’s reach the taller the bar needs to be.

For the Yeti’s 505mm reach and 347mm bottom bracket height, I’d typically choose a bar height of around 1,110mm from the floor to the grips. But with all the spacers under the stem, the bar height measured 1,085mm.

As such, the bar was a little too low for me, but I do use an unusually high bar height; this was apparently not a problem for the other journalists on the launch. This problem could be easily remedied by fitting a higher-rise bar, and I suggested to Yeti that it keeps the steerer longer or spec a higher-rise bar in the XL size.

Setting up the shock was more straightforward. Yeti has compiled settings from staff riders and customers to help recommend spring rates and damper settings based on your weight. At 87kg, the 500lb per inch spring was spot on for me and the damper setup on the four-way adjustable Fox X2 shock was a reasonable starting point too.

I did open the high-speed compression and low-speed rebound a few clicks because, at first, the bike was hanging up slightly when hitting repeated bumps at speed.

Due to the low bar height (for me) I was riding in a slightly squatted position rather than standing tall and leaning forward, as I prefer to do with a long bike, but the geometry is undeniably stable and confidence-inspiring nonetheless.

When bombing through rocky gullies the bike was in its element. The composed Fox 36 fork, wide bar and slack head angle makes for a really confident front end.

I was initially concerned the long stem and short offset would lead to an odd steering feel, but this didn’t seem to matter because the Yeti carves through turns as a slack bike should.

The short chainstay length (relative to the wheelbase) means you have to work a little harder to keep the front wheel weighted properly, but it was never vague. The flip side is that the Yeti is easy to manual and hop for a long bike.

Once the damping was opened up, the rear suspension handled everything well too. It’s still not the most forgiving system, but it feels settled and stable with loads of traction thanks to that soft initial stroke, where coil shocks still have an edge. Perhaps because the linkage is progressive throughout its stroke, so the resistance builds smoothly, there are no odd quirks or surprises form the suspension. It’s consistently supportive and therefore predictable.

When climbing, the SB165 has a pleasant surprise in store. The 77-degree seat angle puts you in a nice and efficient position for tackling steep pitches in relative comfort. I still pushed the saddle forwards to maximise the effect though — I find this improves climbing comfort until the effective seat angle reaches 79 degrees.

Thanks to the high levels of anti-squat near the sag point, the suspension is stable under power, with minimal pedal-bob. It stays high in its travel and responds efficiently when powering up steep ascents.

Inevitably, the suspension does firm up when pedalling, so you can’t just plough through bumps while pedalling hard (lower anti-squat designs do better here), but this can be remedied with better technique.

I’m also very used to (and spoiled by) riding 29ers, so the smaller wheels are of course partly to blame for this firm-under-power feeling.

Which brings me to my only real criticism of the SB165 – its choice of wheel size.

As a tall rider, I perceive no real disadvantage to bigger wheels, and the trend towards longer front-centres demands a more forwards riding position, where bigger wheels get in the way less.

While the Yeti SB165 is impressively stable, composed and efficient, I can't help thinking the same bike with bigger wheels would be just a little bit better. But if you want 650b wheels, and have deep pockets, the SB165 is — so far — hard to fault.