Shimano has filed a patent that strongly suggests that it is finally developing a gearbox for both road and mountain bikes.

Within the patent are details of exactly how the gearbox could work alongside details of a low-friction coating for chainrings and chains that has the potential to enormously reduce the drag of a gearbox – one of the key downsides of gearboxes we've ridden so far.

If this patent becomes reality and is adopted by mainstream brands — which isn’t beyond the realms of possibility, given Shimano’s influence in the OEM market — it could represent a potentially huge change to bicycle design.

It would also make a small but vocal group of diehard gearbox fans very, very happy indeed.

Too busy and important to read this article? Have a listen to our podcast in which we explain the significance of Shimano's patent. Otherwise, keep reading...

[acast acastid="bikeshorts02-isshimanomakingagearbox" accountid="bikeradarpodcast" /]

A brief history of bicycle gearboxes

Before we take a deep dive into this patent it’s worth covering what a bicycle gearbox is, what their claimed benefits are and what might be their drawbacks.

In its most simple arrangement, a gearbox for a bicycle houses all shifting components within a fully-sealed box that is mounted to the frame.

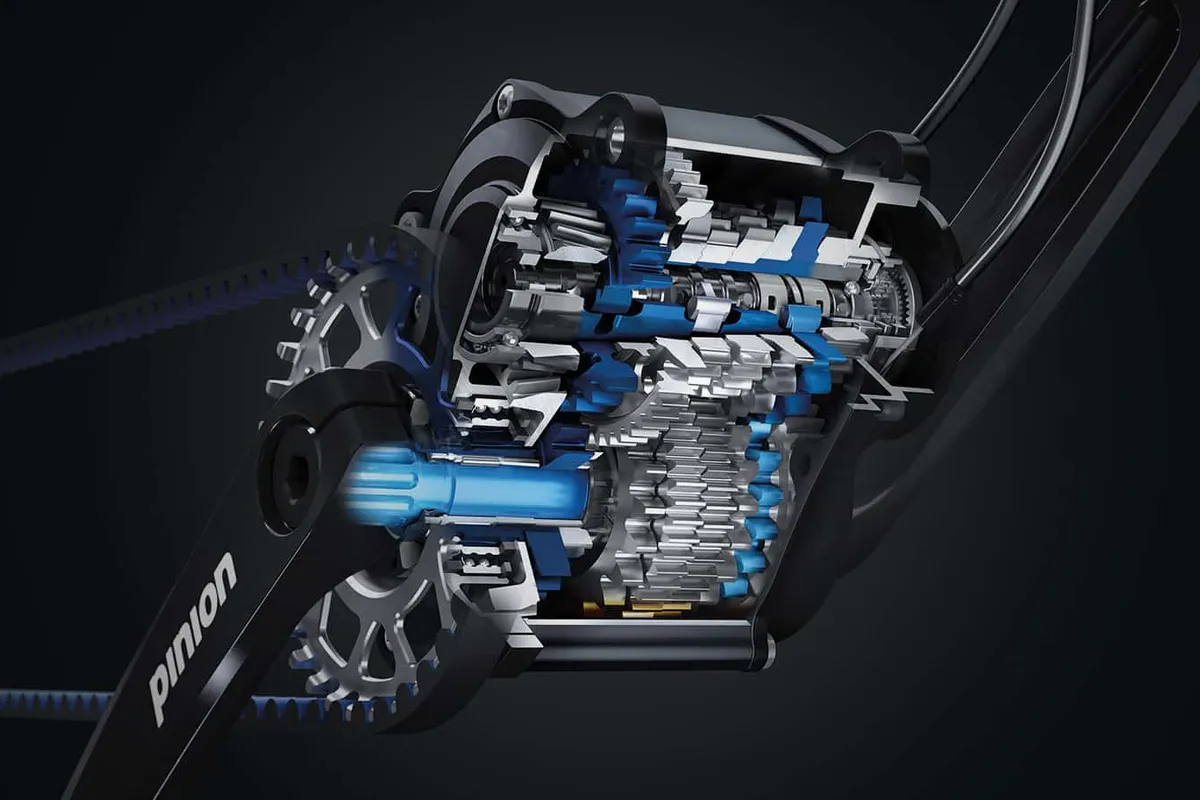

Exactly how this works varies from manufacturer-to-manufacturer, but Pinion — the undoubted leader in the bicycle gearbox market — uses a system of movable, interlocking spur gears to provide six, nine, 12 or 18 gears in a wider range than a typical derailleur drivetrain.

Effigear produces a similar system with a few subtle differences.

We’ve already covered why you may (or may not) want to invest in a gearbox in a previous article but, as a quick refresher, the key advantage of a gearbox is improved reliability and reduced wear.

As a typical gearbox is fully sealed, it is impervious to the elements, hugely extending the time between services. As there are no delicate components dangling from a bike frame, they are also potentially less damage-prone than a typical derailleur drivetrain.

Most gearboxes also allow you to shift without pedalling, which can be useful in certain circumstances.

On mountain bikes, moving unsprung weight onto the frame can also significantly improve suspension performance.

The big drawback of a gearbox is increased drag and weight.

A system of meshing gears typically carries the penalty of increased drag compared to a chain and derailleur drivetrain.

Most systems also come with a considerable weight penalty (usually in the range of 100 to 700g compared to a comparable derailleur drivetrain).

Why is it significant that Shimano is getting involved with gearbox technology ?

Regardless of the potential disadvantages of a gearbox, there is a small but incredibly vocal minority of riders calling out for more investment in the technology.

Pinion and others have worked hard to meet that demand but, as a relatively small brand, it will never have the R&D budget or OEM clout of larger manufacturers.

This is why the potential of Shimano developing a gearbox could be such enormous news. Shimano is by far the biggest bicycle drivetrain manufacturer out there and it has huge development resources at its disposal.

Shimano would also never bother investing in developing such a system if it didn’t believe it could have significant advantages over a derailleur drivetrain.

Shimano has definitely developed some weird stuff, seemingly just because it could in the past (see Airlines), but I also doubt it would bother developing a gearbox if brands weren’t calling for one.

With this in mind, as you will soon see, I think it’s safe to assume Shimano is pretty far down the line with developing its gearbox concept, which, as far as I am aware, is the first of its kind from the brand.

(Before anyone bothers commenting, the pseudo-gearbox based on an Alfine hub that was used on the Zerode G1 doesn’t count).

A foreword

Before we dig our way through this typically opaque patent, I should point out that a huge portion of it is dedicated to describing the lubricant and coating used on the moving components of the proposed gearbox.

While definitely interesting – and I think, reading between the lines, this funky coating and lubricant would be critical to the potential success of this system – I won’t pretend for a moment that I’m an expert on such matters.

The physical makeup of the proposed gearbox is far more interesting to the less chemical-engineering-minded among us and presents a far more compelling concept than a potentially slippery – though no doubt impressive – lubricant and coating.

As such, I will spend more time describing the gearbox here. If you want to read about lubes, fill your boots (with slippery lubricant) and get patent US 2019/0011037 A1 downloaded.

On a similar note, as with all patents, the language used to describe the gearbox is purposefully vague to the point of being obfuscatory.

Patents aim to cover all potential physical outcomes of a design. This is done to ensure another manufacturer can’t copy a concept with a slight variation on a proposed design.

On the other hand, some designers flood patent offices with vague concepts in a practice known as ‘patent trolling’, but that seems unlikely to be happening here and is a topic for another time.

Keeping the language used in mind, working out how a system could work is the real challenge with a patent.

A little bit of imagination, and heavy use of a highlighter, goes a long way when unpicking a patent and this is my interpretation of how this gearbox could work and look. I am happy to be corrected in the comments on any area I may have got things wrong.

How could Shimano’s gearbox work?

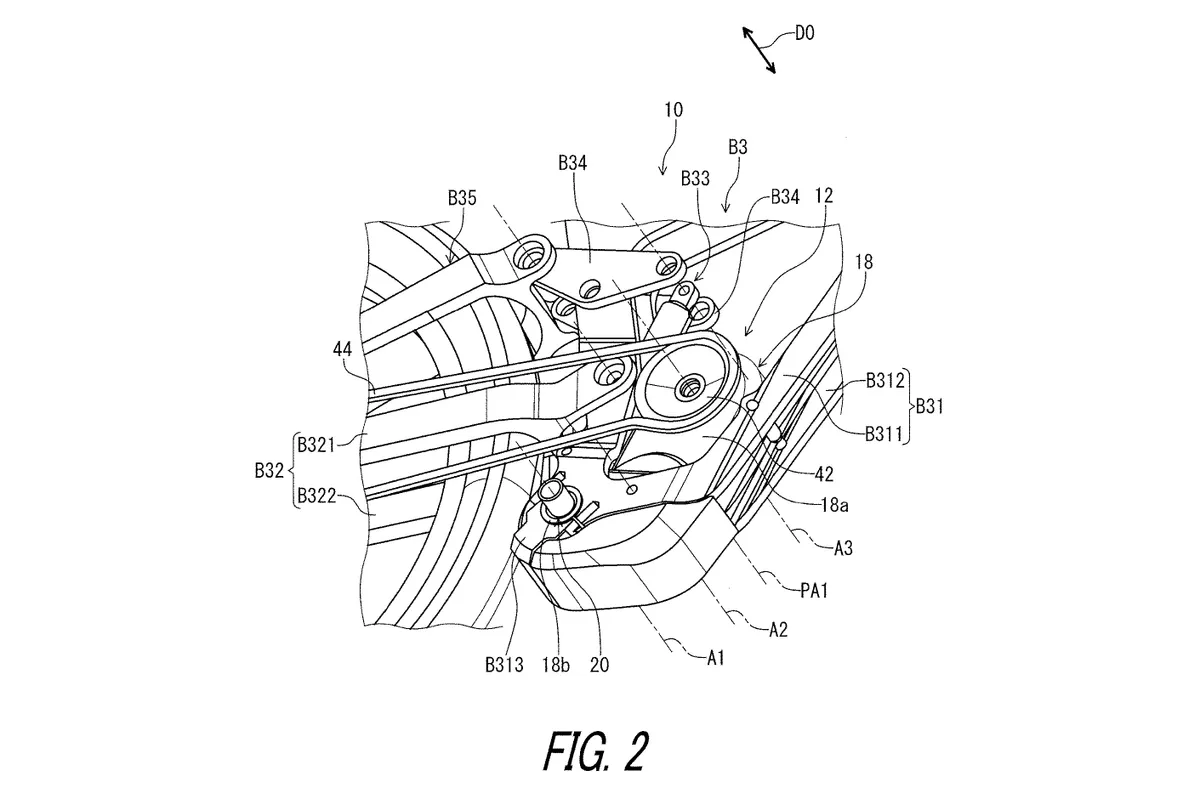

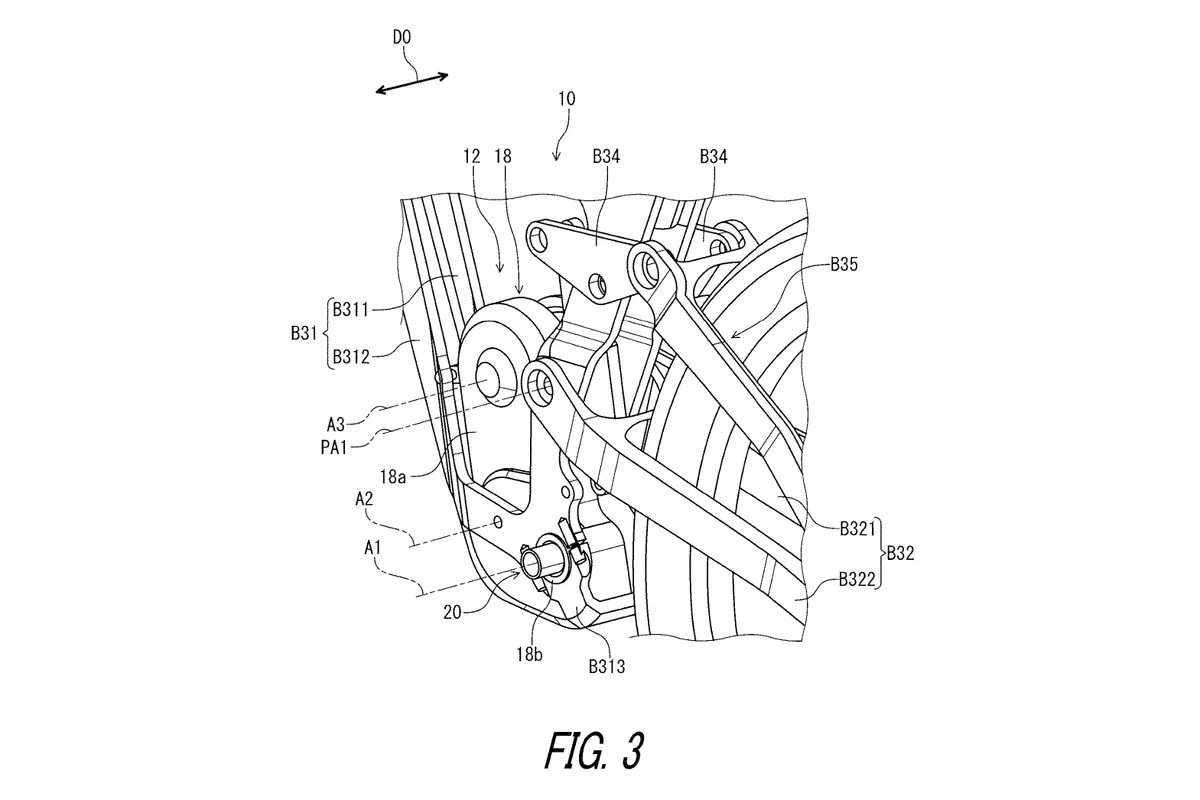

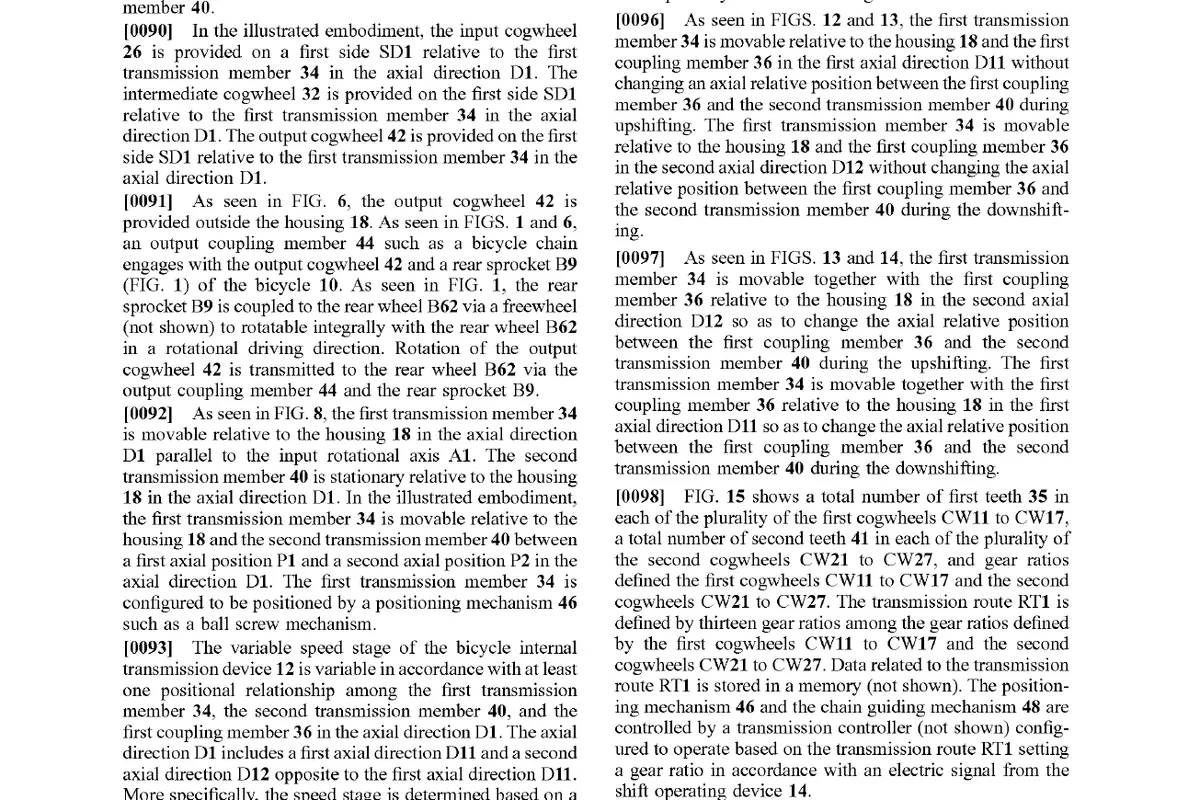

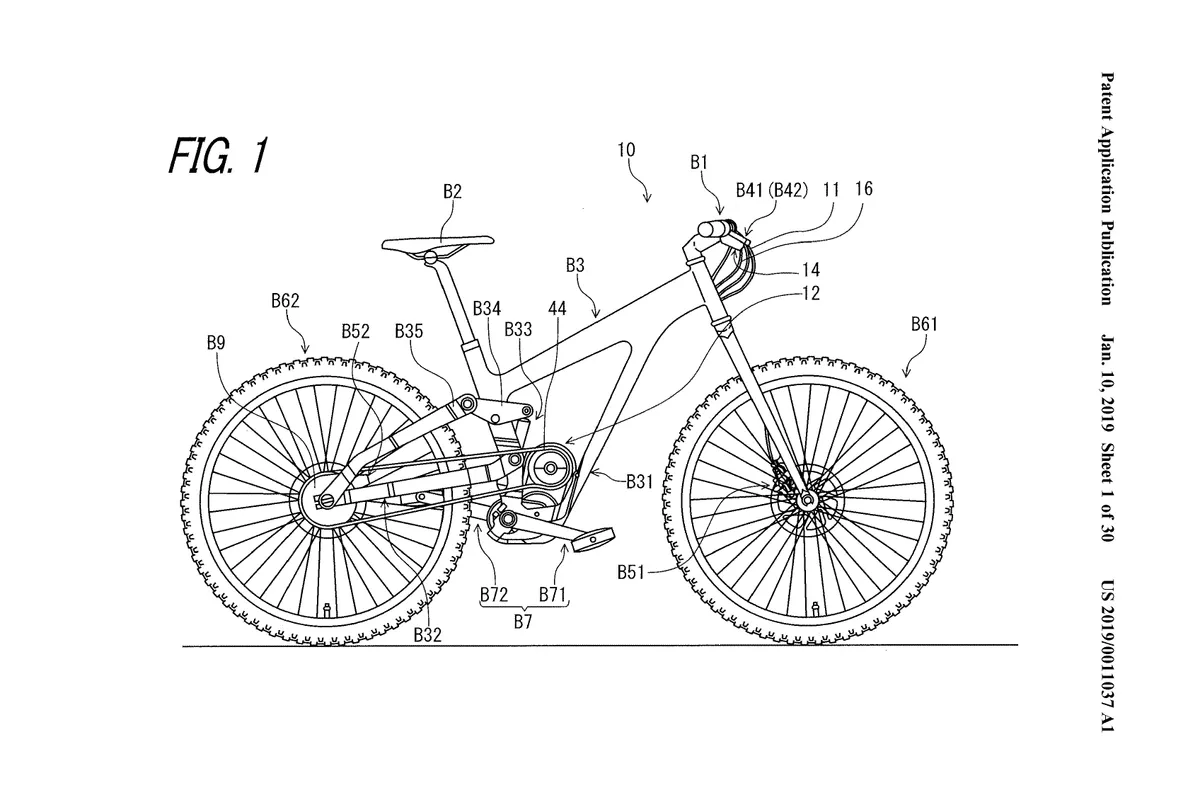

The key portion of the patent describes a gearbox that would mount to the bike around the bottom bracket area.

We are, obviously, just looking at patent drawings here, but the proposed design is similar in form factor to a Shimano Steps e-bike motor. Indeed, looking closely, it seems possible that the lower half of the gearbox could fit into the same mounting pattern as a Steps motor.

The patent also suggests that the gearbox would be a “separate member”, or, in other words, a component that could be removed for servicing or replacement.

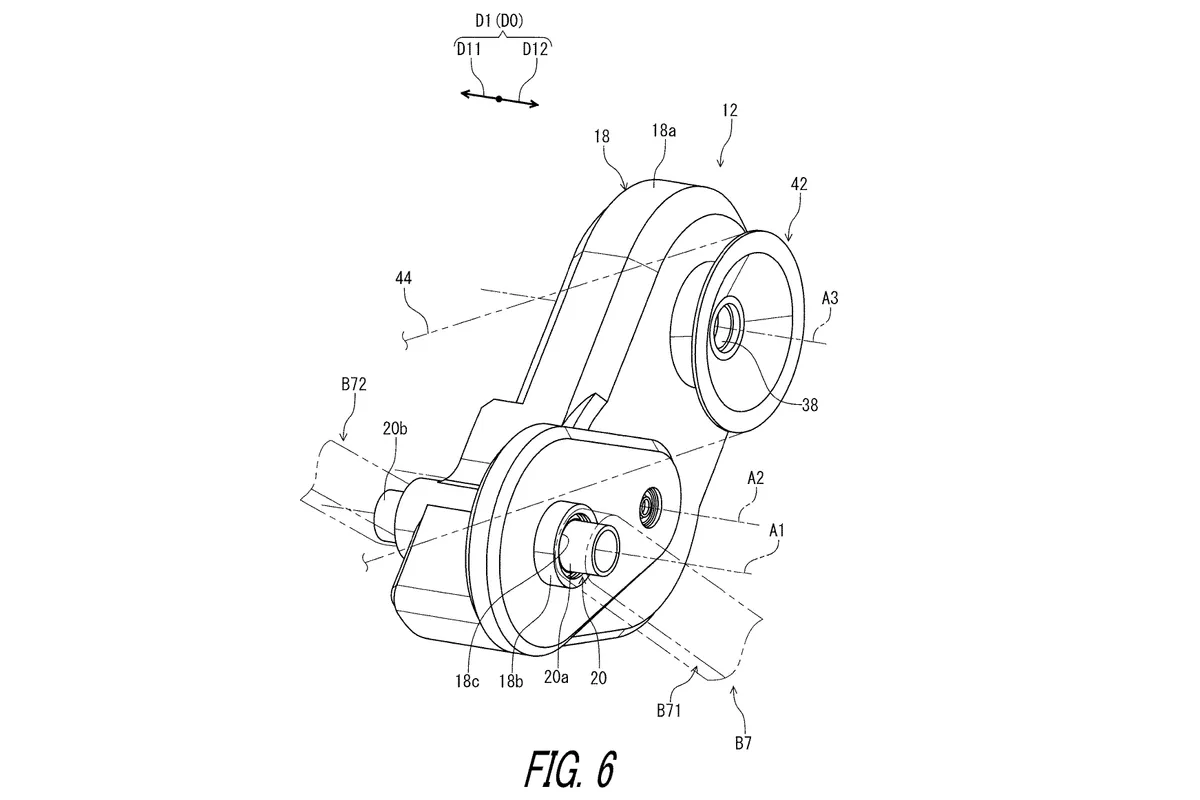

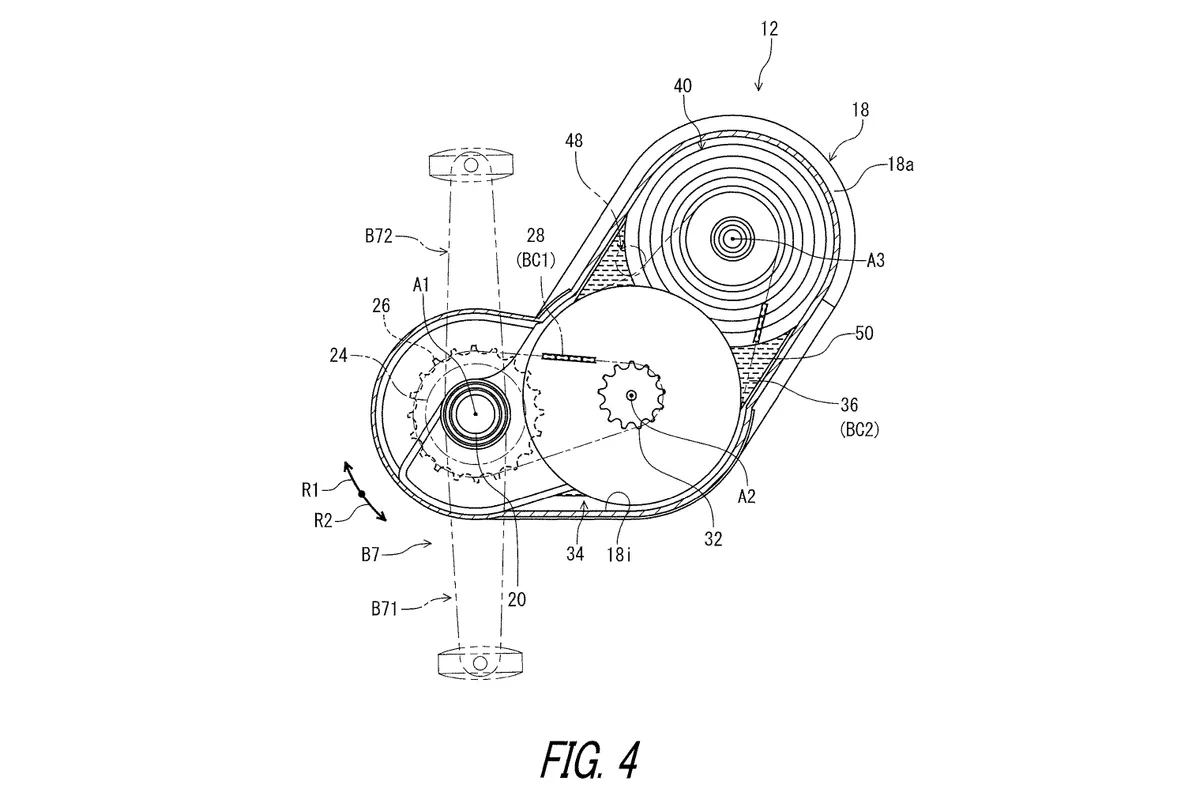

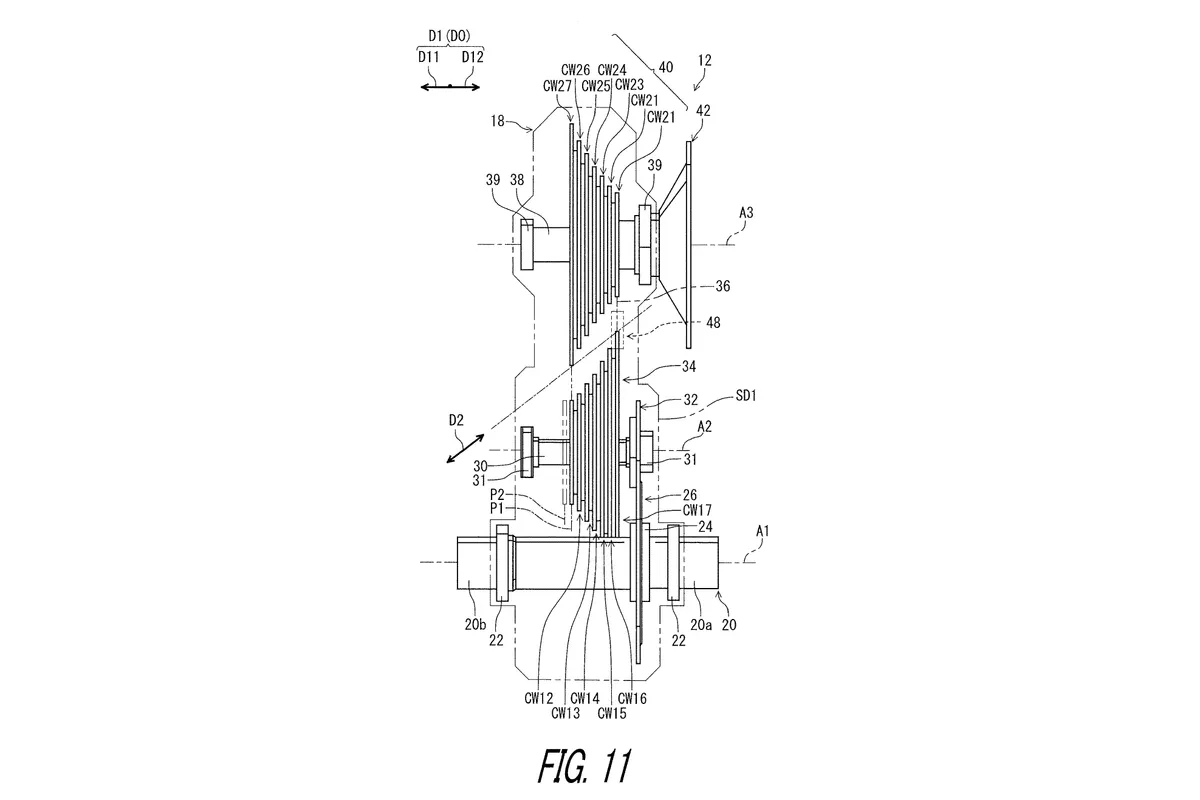

The gearbox is driven by a typical crankset that initially moves a chainring located within the gearbox. This, in turn, drives the first “transmission member” – a vague term used throughout the patent to describe a cassette of sorts – via a chain.

The cassettes illustrated are very typical looking 7-speed ones, with Hyperglide-like ramps and shaping.

A secondary chain then connects to the second “transmission member” located towards the top of the gearbox.

The proposed method for shifting across these two cassettes is very interesting.

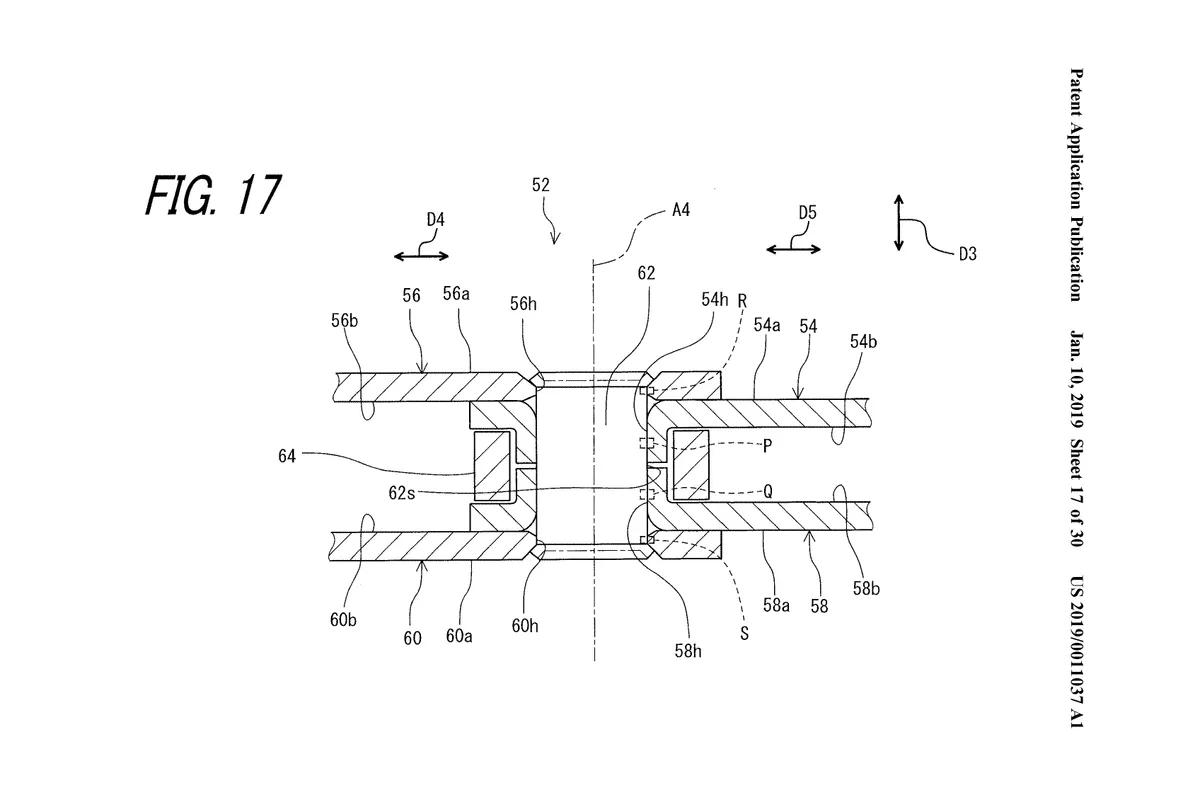

The patent suggests that the first cassette would be configured to be moved by “a positioning mechanism such as a ball screw”.

In other words, the cassette would have the ability to move horizontally along the spindle it is mounted to. The second cassette would remain stationary.

A chain guide that “could take a form similar to a bicycle rear derailleur” would guide the chain between these two cassettes, while also allowing for any change in chain length when shifting between gear combinations.

The ability to move the first cassette along this horizontal axis means that the drivetrain could maintain a perfectly straight chainline at all times.

Compared to a typical derailleur drivetrain, which in most circumstances will have an imperfect chainline, this arrangement has the potential to reduce drag and wear, which would in turn increase efficiency.

For context, any fixed-gear rider will (all too gladly/smugly) delight in extolling the virtues of a perfectly straight chainline — the feeling of efficiency on such a bike is remarkable, and getting back onto a typically geared bike after riding fixed can feel like pedalling through treacle.

The legendary Honda gearbox seen on its RN01 downhill bike took a similar, though simpler, approach by essentially replicating a typical 1× drivetrain inside the gearbox.

Honda used a conventional derailleur to shift between gears on the cassette, while the single chainring was able to slide along its drive shaft to maintain a straight chainline.

In Shimano's patent, the first cassette also moves laterally to maintain the chainline, but the size of the sprocket on both the first and second cassettes changes between gears. Presumably, this allows for a broader gearing range while keeping the system compact, as well as allowing for a smaller chain-tensioner as the combined size of the two sprockets used is similar across the gearing range.

(For those that are interested, legend has it that these bikes were all melted down when the team disbanded in 2004, but the full details of the once-mysterious gearbox that defined this bike are now available via this patent.)

The use of a chain and ability of the first cassette to move along that horizontal axis is one of the key differentiators between the proposed gearbox and competitors on the market.

As mentioned, gearboxes typically rely on interlocking spur gears that, while reliable, can be both very draggy and heavy.

This proposed system has the potential to be very efficient — perhaps even more efficient than a derailleur drivetrain — and, compared to the competition, relatively light.

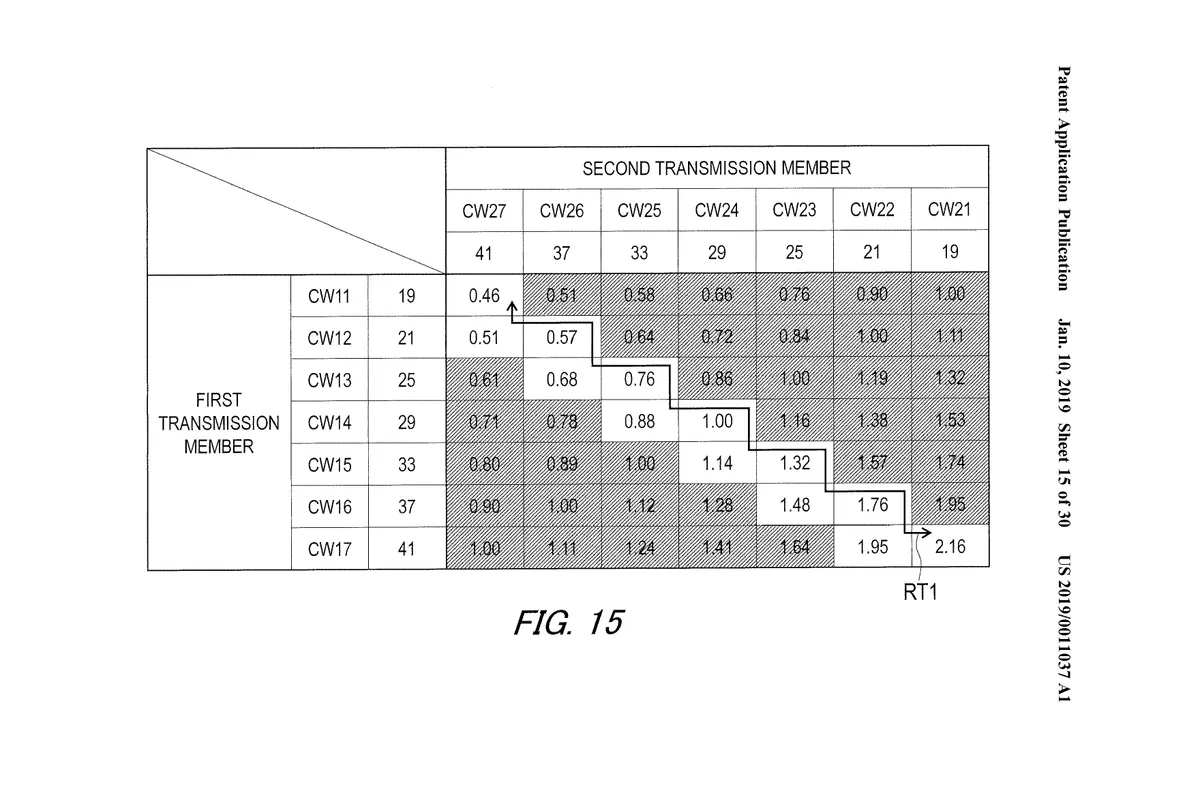

The patent goes on to suggest the gearbox would have “thirteen gear ratios”.

The above table suggests that six of the seven sprockets on the first cassette could each be used with two different sprockets on the second cassette, creating a total of 13 distinct gear ratios. The available ratios go from 0.46 to 2.16, creating a gearing range of 470 per cent. That's slightly less than the maximum range offered by Shimano's (510 per cent) and SRAM's (500 per cent) 12-speed mountain bike drivetrains.

The “transmission route” (i.e. the pattern in which the gears would shift) would be “stored in memory”. The movement of the cassette positioning system and the “guiding mechanism” would be controlled by a transmission controller.

As an aside, I think the fact that the patent explicitly states the gearbox would be 13-speed is a hint as to how seriously Shimano is taking this patent. If they’ve gone as far as working out the limits/optimum gearing of the gearbox, it could well be a near-finished design. Though, I may be completely wrong.

Why they wouldn’t go the whole hog and jump to 14-speed is another question.

The patent suggests the shifting mechanism itself — which, as a reminder, would involve moving that cassette across the spindle on a ball screw — would be “electrically actuated”.

In other words, a small motor would push or pull the cassette along this axis. A similar form of technology already exists in Shimano’s Alfine Di2 hubs.

Weirdly, the patent suggests this mechanism could be actuated by a mechanical gear cable, but also opens up the possibility of it being electronically or wirelessly controlled. I think either of the latter two is far more likely.

Shifting the gearbox would be done, as with a typical drivetrain, at the handlebars. This could take the form of a typical flat bar shifter or could be “integrated into the front brake operating device”, suggesting that a road-style shifter could also be developed.

It could also suggest a return of Shimano’s infamously terrible DualControl mountain bike levers, but I’m doubtful anyone would want to revive that idea.

Hidden away in a tiny little sentence is a fairly revolutionary suggestion, with Shimano hinting that as well as indexed gears it would be possible to design the gearbox to have a “continuously variable speed stage if needed/desired”.

Otherwise known as a continuously variable transmission, or CVT, this provides stepless gears that can be infinitely adjusted to suit the terrain and speed.

Nuvinci already produces a CVT hub based on a similar concept. Exactly how this kind of technology could be ported into a gearbox isn’t described in the patent.

Will this gearbox be just for mountain bikes?

No. The patent explicitly states that “while the bicycle illustrated is a mountain bike, the bicycle internal transmission device [gearbox] can be applied to road bikes or any type of bicycle”.

A full-suspension bike would presumably require a chain/belt tensioner to allow for the increase in chain length when the suspension compresses. This isn't necessary for hardtail applications.

What about weight?

As well as drag, weight is where a typical gearbox falls down for the weenies among us, and you can expect to add something in the range of 200 to 700g with a gearbox compared to an equivalent derailleur drivetrain.

Unfortunately, this patent makes no reference to the weight of the system. It also doesn’t make any reference to any potential weight savings the system could present compared to a typical gearbox.

However, making my own assumptions, as the gearbox is more like an enclosed derailleur drivetrain than a system based on interlocking spur gears, I can imagine that weight could possibly be significantly reduced — a cassette will likely be lighter than a chunky spur gear but, again, that is speculation.

What about the chain and this coating?

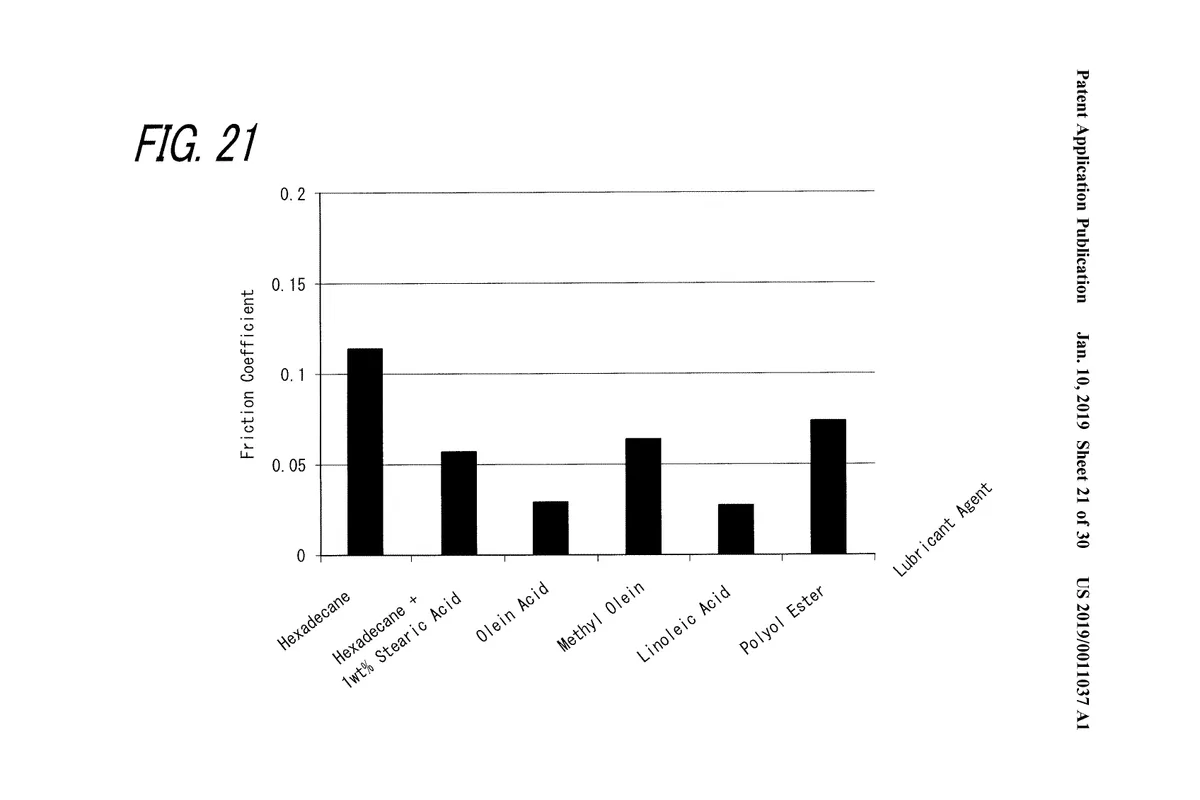

Central to the success of this concept is a special-sauce lubricant, a new-fangled coating for the moving components and a special way of making the most of that lubricant.

As I mentioned, passing judgement on what is proposed with this lubricant and, more importantly, how it compares to existing options, is beyond the scope of this article and my knowledge. If someone would like to explain how a lubricant containing a “fatty acid containing a carboxyl group” and “further preferably” a form of “linoleic acid” compares to your typical lube, be my guest.

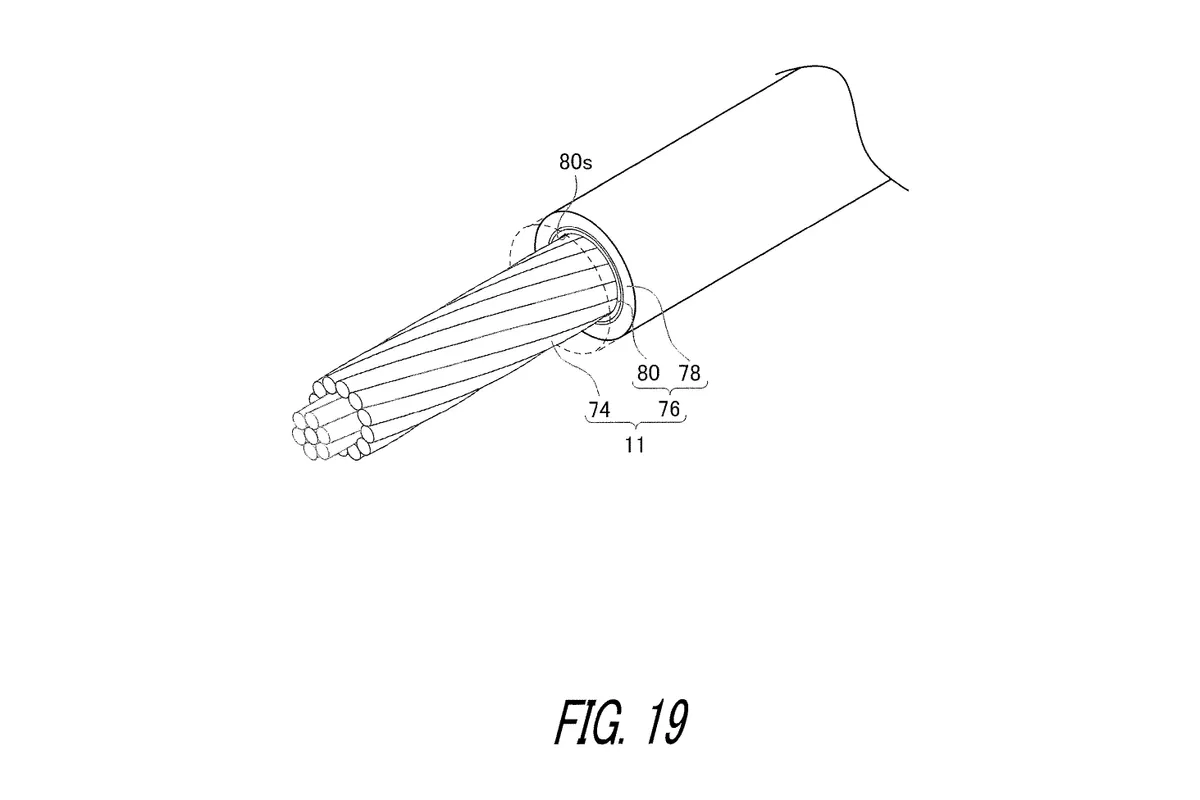

The last point on how the chain could be designed is worth dissecting though.

Sections 0100 through 0103 of the patent essentially describe a conventional bicycle chain. However, section 0104 through 0106 describes how small holes or textured surfaces formed into the pins and plates of the chain could be used to hold a small amount of lubricant.

In a typical derailleur drivetrain, where the chain would be exposed, these textured surfaces and holes would accomplish nothing but accumulating dirt. However, in a fully-enclosed gearbox, it would mean the chain could remain constantly lubed with fresh lubricant, reducing drag.

On that note, the patent suggests that the gearbox would be “configured to store lubricant in [an] internal space” that would constantly lubricate both of the chains, the first chainring and both cassettes.

The ability to keep everything lubed with this special sauce, alongside the ability to run a perfect chainline, could be key to reducing drag, which, as mentioned, is the major drawback of extant gearboxes.

The patent goes on to describe in section 0110 through 0120 how the same lubricant could also be used on a “bowden cable” (i.e. a brake or gear cable) to reduce drag, provided the cables could be sealed.

The rest of the patent goes on to describe how the same technology could be used to reduce drag in a conventional internal gear hub.

It is outside the scope of this article to go into depth here but, if such things interest you, I recommend you read through the patent for all of the juicy details.

To me, the concept of a frame-mounted gearbox developed by Shimano is also a far more compelling idea than a marginally more efficient hub gear.

What does Shimano say?

We contacted Shimano for a comment about the patent. The response? "Shimano has chosen not to comment".

Will Shimano actually ever make a gearbox?

The concept of a gearbox has captured the attention of cyclists the world over for years now.

Nearly every time we post a story about a new drivetrain there’s a small but significant number of voices calling out for a lightweight, low drag and reliable internal gearbox.

As mentioned, the potential benefits of such a gearbox are clear: reducing unsprung mass, keeping delicate components out of harm's way and sealing moving parts from the elements are all deeply appealing propositions.

However, what is necessarily good for (some) cyclists is, to a point, almost irrelevant in this case because derailleur drivetrains have been developed to the point of near-perfection for the past zillion years. For the largest drivetrain components manufacturer in the world to make a U-turn on that would be incredibly significant.

Likewise, nearly every bike out there is designed and built with a derailleur drivetrain in mind.

While Shimano obviously has enormous power to sway bicycle design, it’s hard to imagine that such a significant shift would happen, at least not quickly.

On the other hand, there’s every chance that there are heated meetings happening in the hallowed halls of The Big Bike Industry that could signal a sea change in bicycle design.

What would drive this change is worth considering.

The cynics among you could very well point to my analogy about derailleur drivetrains being near-perfect and point to gearboxes as ‘another excuse just to sell us something new’.

On the other hand, if you’re feeling generous, consider the development of a super-efficient and lightweight gearbox from a road performance point of view. If this gearbox could be shown to be more efficient than a derailleur drivetrain, the go-fast road weenies will go wild for the idea.

Let’s also not forget that with a large chainring, front and rear shifters, and a cassette out of the way, this setup also has the potential to be more aero than a derailleur drivetrain. Scoff all you want, but this stuff matters to some people!

To conclude, daft as it may sound, I also think that how I found this patent suggests Shimano is seriously considering taking this idea further.

I make a habit of periodically checking on the patents filed by a number of big brands (watch out, The Big Bike Industry, I’m your worst nightmare) and I stumbled on this one almost by accident. The title of the patent hardly suggested something thrilling and a gearbox from Shimano for goodness sakes was the last thing I expect to uncover.

If I were to put my sleuthing hat on, one could assume Shimano is being coy in not using the word gearbox anywhere (not once!) in the patent.

Is this an attempt to stop news getting out about an upcoming enormous announcement or something much more innocent? I like to pretend that I’m a real patent sleuthster and that it’s the former.

With all of that said, one assistant editor’s enthusiasm for a concept isn’t going to change the course of bicycle design — it’s you, the people, who will decide.

What do you think? Are we going to see a truly mammoth change to how bikes are built in the future? — and, to be clear, I think Shimano producing such a component would be incredibly significant. Are you crying out for gearbox development? Or are you quite happy with your derailleur drivetrain, thank you very much? As always, let us know in the comments.