If you’ve ever thought that there’s nothing new in bikes then this 120-year-old hub design kind of proves you right.

- How this engineering student has reinvented the wheel

- Shimano electronic gears could soon charge themselves

- How road buzz could be turned into free energy

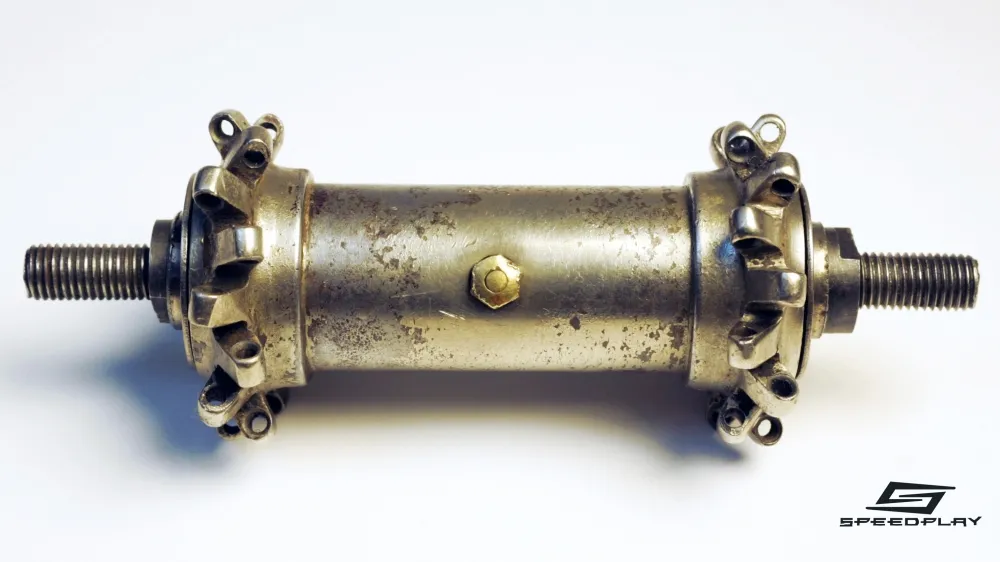

Spotted on the Speedplay Component Museum Flickr, this all-steel, solid axle front hub is in some respects very much of its time; the main body is a simple steel tube with what appears to be a grease port, and it looks like a standard cup-and-cone design with lock-nuts and cones threaded onto the axle.

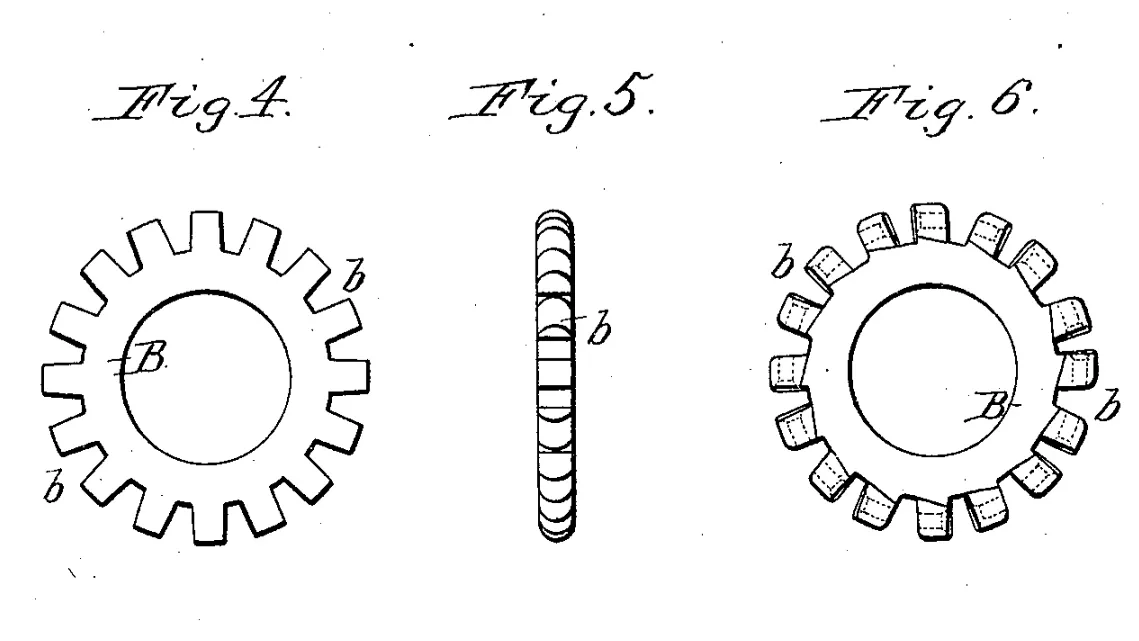

The flange design however is achingly modern — instead of the usual flat discs drilled for J-bend spokes, the Mather hub has funky offset lugs for straight-pull ones.

Photo: Speedplay Component MuseumWe can’t know for sure when the hub itself was made, but it carries a date corresponding to US patent 613701A filed in 1898, which you can download and read here on Google Patents.

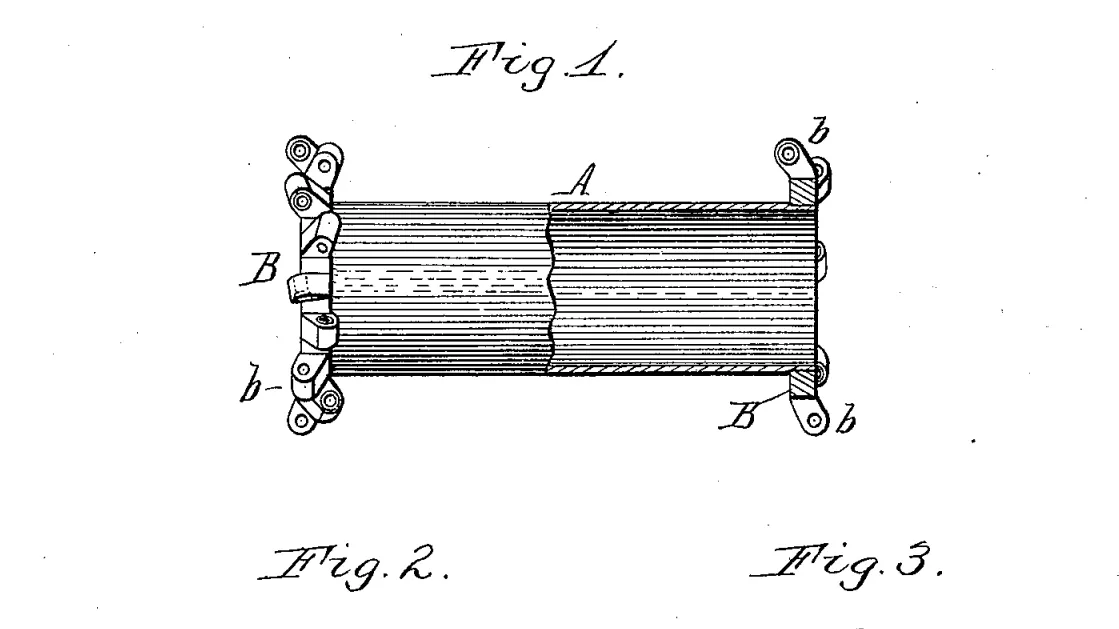

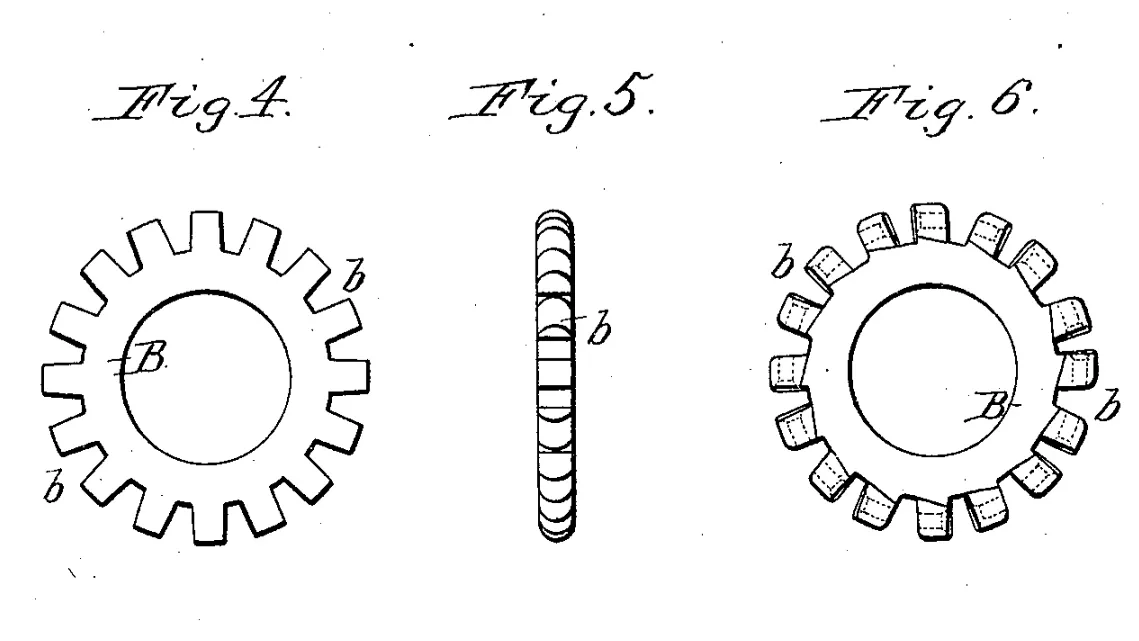

In it, William H. Mather of Cleveland, Ohio proposes an invention relating “to the hubs of wheels having wire spokes which are attached at their inner ends to projecting flanges on the ends of the hub, and more particularly to wheel-hubs having flanges provided with perforated radial lugs for receiving tangent spokes with straight ends.”

What he was describing is hardly different to the straight pull hub designs favoured by many manufacturers today, and the thinking behind it isn’t completely alien either.

Mather states that “the objection of my invention is the production of a hub... which has its lugs so arranged that the intersecting spokes clear one another for preventing wear and rattling of the same and which is light in construction, cheaply manufactured, and neat in appearance.” While spoke wear and “rattling and singing” (as he later charmingly mentions) aren’t major concerns on a properly built bicycle wheel these days, weight and aesthetics certainly are.

In addition, straight-pull designs make for very rapid lacing, which is an important consideration for mass production, so cheap manufacturing remains a valid justification for using this approach.

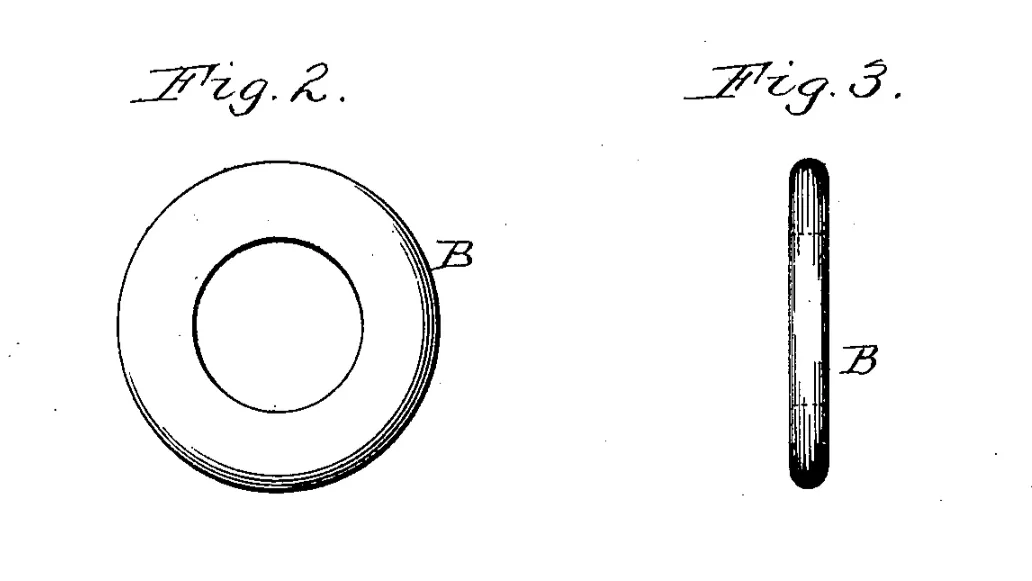

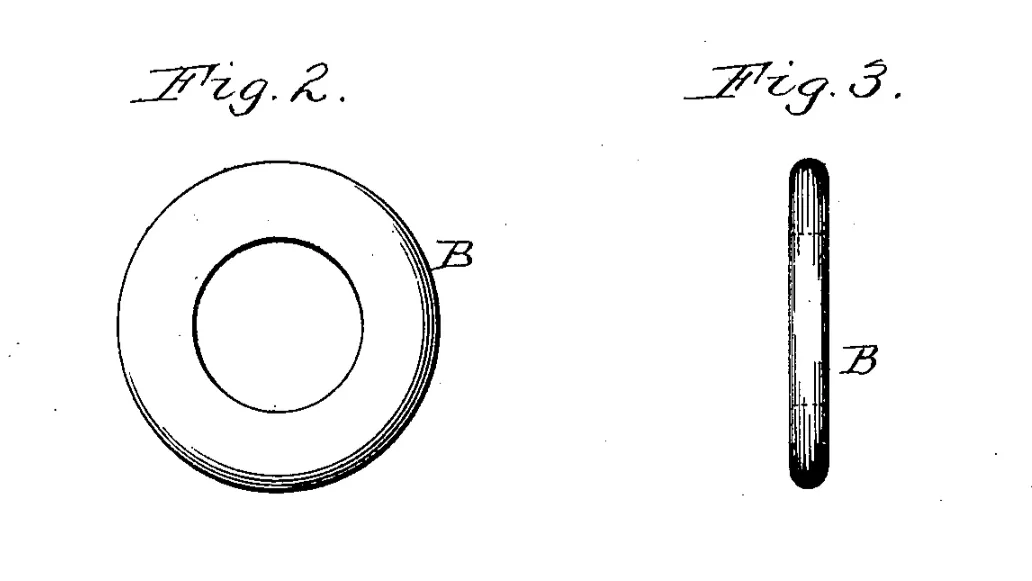

Mather’s patent even goes so far as to describe the manufacturing process, suggesting that the hub flanges could be be produced cheaply by first stamping out rings of steel, then punching recesses in those rings to form “lugs.” The lugs could then be offset alternately and drilled (or “perforated”) for spokes.

Brimming with confidence, Mather asserts that his “improved hub is not only comparatively light and inexpensive, but the peculiar arrangement of its spoke-lugs renders the same very neat and attractive in appearance.” Modern day wheel manufacturers obviously agree, because straight-pull hub designs are everywhere.

Even leaving aside lacing considerations, the appeal is obvious. They look cool and with no spoke elbow to contend with, the most common point of breakage is eliminated.

I do wonder if Mather anticipated the use of bladed spokes however, or if indeed they existed back then. The one real issue with round straight-pull spokes is that if they seize at the nipple they are very difficult to release, because there’s not much to grab onto.

In any case, it’s fascinating to come across a design as forward-thinking as this, from an age long before the invention of derailleurs, or even quick-release skewers.

Thanks to Speedplay for kindly allowing the use of images from its museum.