Trek recently unveiled several 2015 mountain bikes, including the redesigned Fuel EX and Lush, both available with 27.5in wheels, along with a carbon version of the Remedy 29. Mounted to these updated models is a new Fox CTD shock with internals developed by Trek and Penske Racing Shocks. Dubbed RE:aktiv, this new shock brings regressive shock technology originally developed for Formula One racing to mountain bikes.

From racetrack to singletrack

For readers not familiar with the company, Penske Racing Shocks is a high-end automotive suspension manufacturer that was spun off from the Penske’s racing programs. Since 1987 it has supplied suspension products to Formula One, Indy Car and Moto GP teams.

Trek feels Penske's regressive valving has a place in the mountain bike world

Penske initially developed its regressive damping in response to a ban on computer-controlled suspension by Formula One’s governing body in the mid 1990s. Drivers wanted very firm suspension feel for improved feedback. While firm suspension provides the driver with improved tactile feel, it also tended to decrease traction. Penske’s solution was to develop a suspension damping system that felt firm over smooth terrain but, in the words of a Penske suspension engineer, “got out of its own way” when it encountered larger, high-velocity impacts.

Trek’s partnership with Penske began five years ago as a result of a chance meeting at a NASCAR race. The two companies worked together to scale down the technology for use in mountain bike suspension, but it took the mass-production expertise of Fox Racing Shox to bring it to market.

Unlike Fox Racing Shox, Penske Racing Shock only produces dampers for the highest echelons of automotive racing. Penske currently supplies six Formula One teams with bespoke suspension products

Trek used its longstanding partnership with Fox to bring the technology it developed with Penske into a production-ready product suitable for mountain bike use.

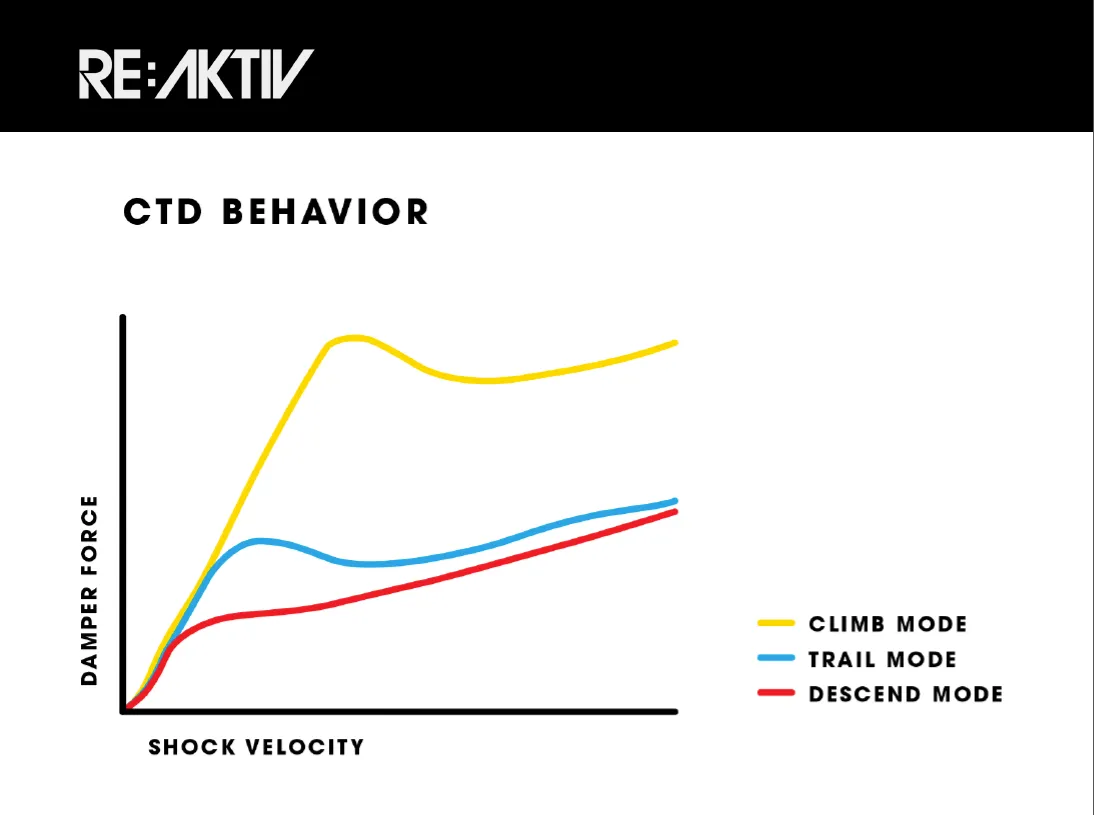

Trek retains its DRCV air spring and adds a damper that improves pedaling performance by increasing low-speed compression damping, while allowing the shock to handle larger, high-velocity impacts without feeling harsh.

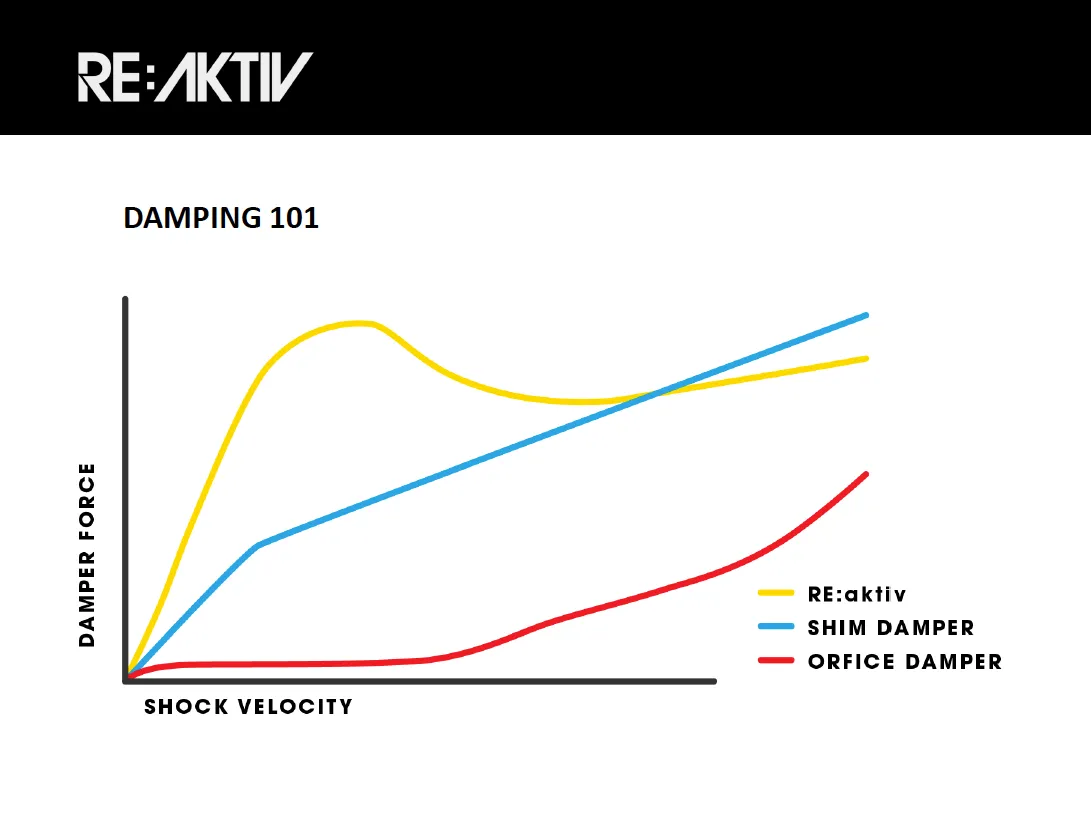

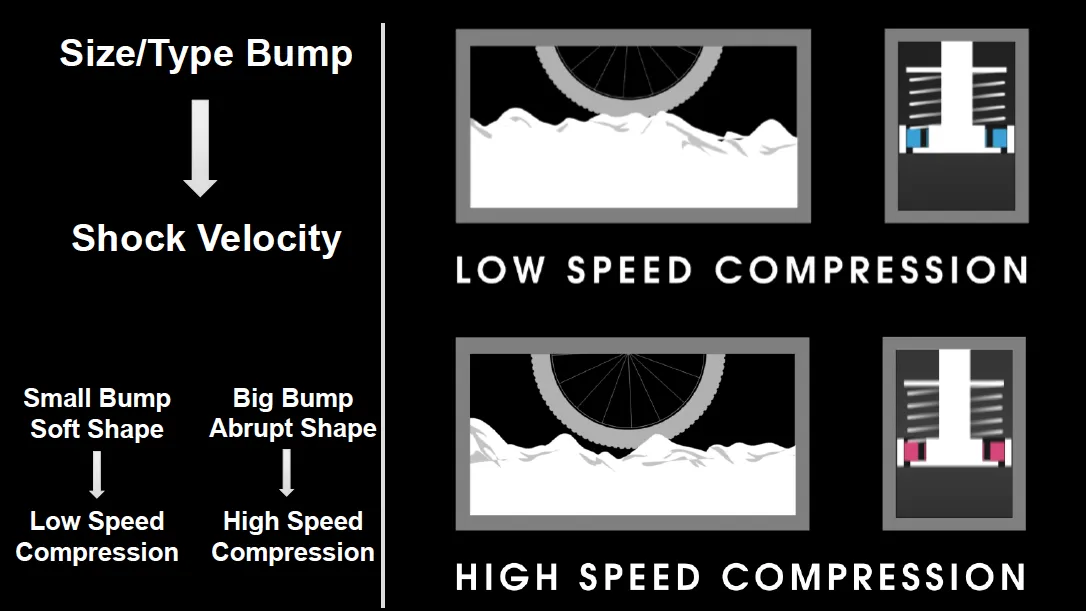

Re:aktiv creates a sharp “nose” in the damping curve that drops away as velocity increases. When suspension engineers talk of shock velocity, they are not necessarily referring to the speed the rider is traveling, but the speed with which the suspension moves in response to an impact

Example: Riding over a rounded rock gradually compresses the suspension (low-velocity impact). In contrast, riding over an obstacle such as a square-edged rock will cause the suspension to compress much more rapidly (high-velocity impact)

Trek’s suspension engineers sought to develop a shock that would open for impacts at a given velocity, while retaining a firm pedaling platform.

Former World Cup racer turned Trek mountain bike product developer Travis Brown noted that, in addition to improved pedaling performance, RE:aktiv damping technology also improves cornering performance by offering more support as the bike pushes through the apex of turns and berms, making it easier for a rider to stay on their preferred line.

How RE:aktiv works

Trek’s suspension R&D expert Jose Gonzalez walked BikeRadar through the inside of the new RE:aktiv damper.

Gonzales heads-up Trek's suspension R&D facility in Santa Clarita, California

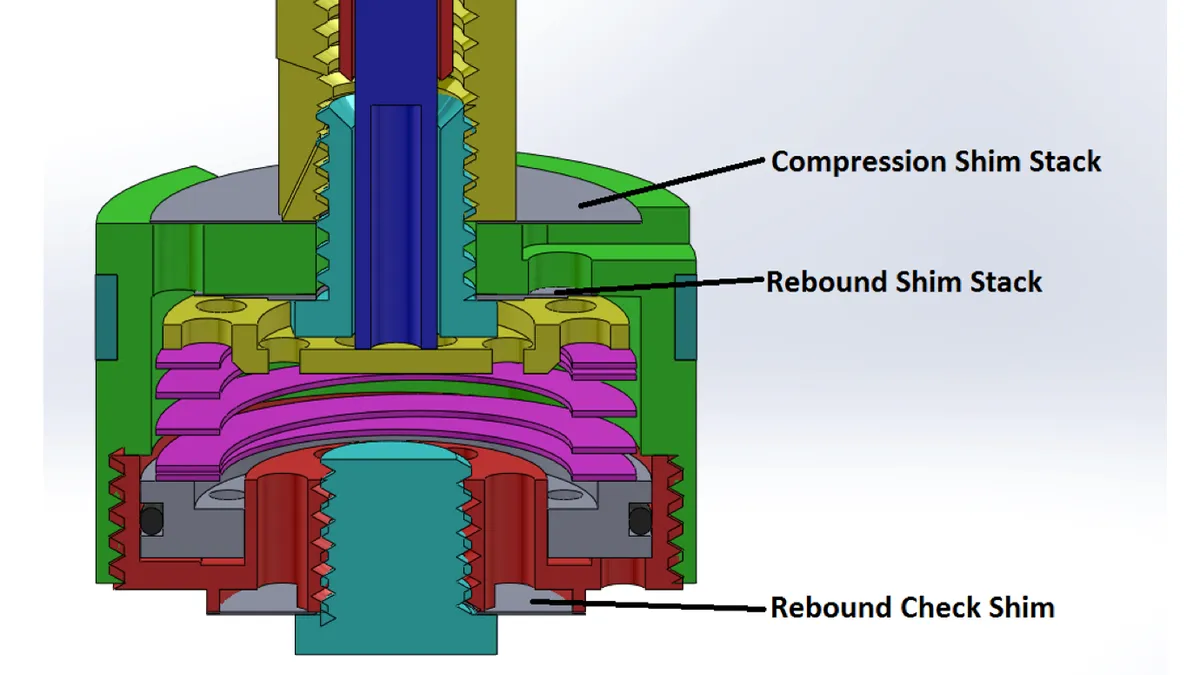

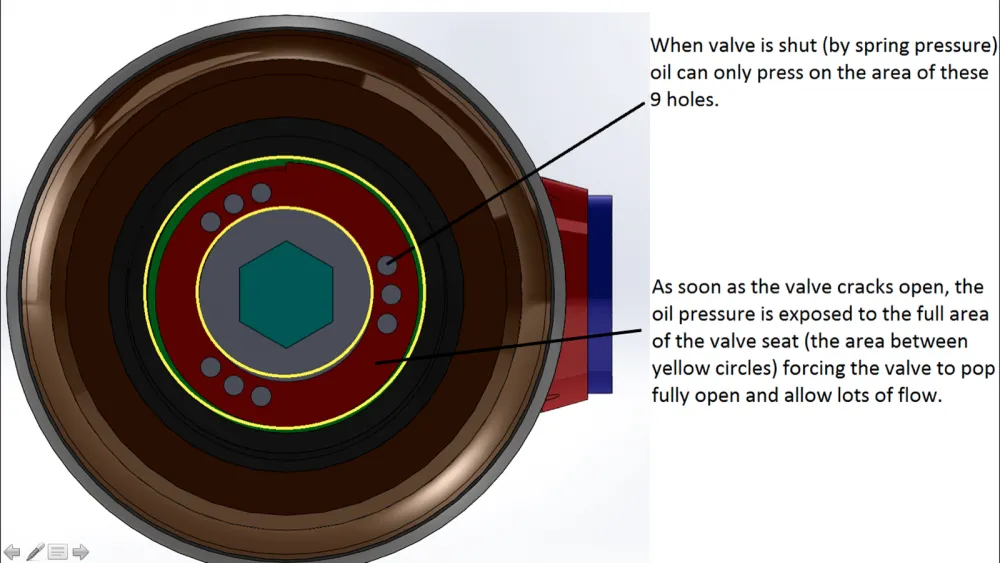

According to Gonzalez, the damper is based on a cavity piston. The piston houses the valve inside of the piston, not outside like traditional layouts. The inside of the piston is sealed off by a piston plate.

Inside this cavity are the regressive valve spring (shown in pink) and the regressive valve plate, which controls the springs characteristics and oil flow

The piston plate has ports that expose a specific amount of area, allowing some oil flow, but not enough to allow the shock to be fully active. It takes a high-velocity impact to open the plate. Once open, the platform drops away and the suspension becomes fully-active

It’s not that it requires a specific amount of force; it’s the rapid increase in force that causes it to open. When the suspension encounters a high-velocity impact, the plate opens to exposes additional area. This movement is enough to allow the valve to open further.

“The valve is dynamic, it’s not that it just pops open; it opens as needed,” Gonzales said.

Trek and Penske are not the first to employ a regressive damper, though the companies took things a step further by introducing a secondary shim valve to provide additional support.

In a typical regressive design, once oil has flowed through the ports and past the flow area controlled by the valve plate, its job is done. Trek introduced a secondary shim valve that controls the suspension over rolling terrain and in G-out situations — places where the rider encounters (and produces) really low-velocity movements.

“Regressive on its own didn’t have the level of stability control that we wanted for those specific situations,” Gonzales said.

Without this additional shim the suspension would blow through its travel, rather than take a more poised, controlled stance.

For 2015, the RE:aktiv shock technology is being incorporated into Trek’s Fuel EX, Lush and Remedy trail bikes. It’s likely that the technology will see expanded use in the coming years