Take a look at the vast majority of high-end road bikes and one trait unites them all. There isn’t a cable, hose or electrical wire in sight.

The trend for integrated routing sees any gear cables and hydraulic hoses concealed at the front end. The result? A clean aesthetic and purported aerodynamic benefits.

Although there’s a vast array of designs on the market, the majority of integrated systems see the cables and hoses routed into the head tube and through the headset bearings before heading to their respective locations.

They are often, but not always, routed through the handlebar and stem, and it’s also quite common to see brands opt for a one-piece bar-stem, again in the name of a sleek, aero-enhancing design.

The trend for integration was largely kick-started in the summer of 2015 with the release of two aero road bikes – the Trek Madone 9 and Specialized Venge ViAS.

Integrated routing is now near-ubiquitous on the best road bikes, while integration is also becoming more popular on gravel bikes and mountain bikes. It’s even starting to appear on commuter bikes, such as the Trek Dual Sport 2.

In fact, it’s now rare to see a mid-to-high-end bike with more ‘traditional’ internal cable routing, where the cables sprout out from the handlebar and enter the frame via a down-tube port.

That said, two exceptions here include the recently released Lauf Úthald and the new Specialized Roubaix, though the latter’s potential for front-end integration is limited by Specialized’s use of the bump-taming FutureShock system.

While integration may look clean, routine maintenance tasks such as servicing or replacing a headset, or simply changing a gear cable, have become significantly more involved.

Quite simply, are the aesthetic and claimed aerodynamic benefits of fully integrated cable routing worth it?

We spoke to five mechanics from a range of different backgrounds to get their opinions on the topic, including the most annoying aspects from a maintenance perspective, what the typical labour costs are and how they would improve integrated designs.

What's most annoying about integration for bike mechanics?

All of the mechanics we spoke to agreed the most annoying aspect of integration is headset replacement.

Rohan Dubash has more than 40 years of cycling industry experience and co-authored Bike Mechanic: Tales from the Road and the Workshop with ex-Rouleur editor Guy Andrews. He now works as a private mechanic, referred to as Doctor D. His Facebook page, where he details each element of the bikes he has in for service, is a treasure trove of insightful tips and tricks.

“Relatively simple jobs that used to take say 30 minutes can now take several hours,” Dubash told BikeRadar, “and the sad truth is that for the majority of cyclists, all this fancy, streamlined aero kit has few genuine benefits.”

Hydraulic hose woes

In order to replace a headset, any gear cables or hydraulic hoses that run through it need to be disconnected.

With the exception of SRAM’s Stealthamajig, the hydraulic hose needs to be cut when removed because the olives and barbs – the parts installed onto each end of the hose – aren’t reusable. When it then comes to refitting, unless the previous mechanic that worked on the bike left a little extra length (or you’ve gone through that length), the hose is often too short and therefore requires complete replacement.

The brake then needs to be bled and handlebar tape rewrapped on a drop-bar bike. And that’s after the headache of having to manipulate cables and hoses through tight handlebar or stem routing.

Luke Wallis has extensive workshop experience, wrenching at Pearson Cycles, Sigma Sports, Canyon’s UK warranty department and Carbon Bike Repair.

In addition to the more tedious labour required, his major grievance with integrated systems is “the one-use aspect of items such as brake hoses and inserts, bearings and bar tape”. He feels it’s wasteful having to bin perfectly good items for the sake of replacing a headset bearing.

This is corroborated by Jamie Watkins, another cycling industry stalwart who has worked in a variety of roles, including previous positions at Sigma Sports, iRide and Carbon Bike Repair.

He criticises “the often inadequate space and harsh angles coupled with the need to be born an octopus holding onto five things at once”.

Small parts, complex solutions

Integrated systems typically consist of small parts, such as clips to hold any cables or hoses in place, or wedges if the steerer tube is D-shaped.

Watkins goes on to bemoan how integration can cause “wear issues for the cables strapped in place”. Cables and hoses are often subjected to tight angles as they are run through these intricate systems. This can make brake bleeding more difficult, because the hose isn’t run in a straight line and air pockets can get trapped in the tight corners.

It’s more of an issue for mechanical gear cables though, with the tight angles they are subjected to introducing unnecessary friction. Gear cables perform best when they are run in as direct a line as possible. Poor shifting quality, therefore, is a common complaint.

It’s why an increasing number of brands are designing their frames specifically around electronic groupsets, because the shifting quality doesn’t suffer if the wires take an awkward route. It isn’t an issue at all on SRAM AXS systems or Campagnolo Super Record Wireless, precisely because they are wireless.

Additional wear and tear

Watkins says hydraulic hoses suffer, too, because they are often held very tightly in place and can become pinched or subject to adverse wear. He says he has regularly seen hoses wear down to the base plastic, as a result of half-considered solutions, and pinching issues where “although the brake lever felt solid, fluid wasn’t flowing [through the hose] so the brake didn’t operate”.

Watkins says he is yet to find a brand that offers a good solution from a mechanic’s point of view, but is keen to point out “some brands are worse than others”.

A lack of standards

Tommy Barse is the owner of Cutlass Velo in Baltimore, Maryland, and specialises in servicing and custom bike builds. His Instagram account (@cutlassvelo) is well worth a follow.

Barse is annoyed by “the lack of a standardised approach to bearings, the steerer assembly, handlebar routing and process”.

For the most part, integrated systems are developed by the bike brand and can often even be model-specific. For example, Trek uses a different handlebar and stem arrangement for its Domane and Madone models

As such, brands use differing headset bearings and cable routing methods. If you’re a mechanic who works day-in, day-out on certain brands, you soon get used to those brands' philosophies, but many of the mechanics questioned for this article are required to to work on all brands and bike models.

And if the lack of standards is confusing for experienced mechanics, how can a home mechanic be expected to work confidently on proprietary designs with no standards across the industry?

An expiry date for your pride and joy?

Dubash furthers this argument, suggesting “your fancy new road bike now has a ‘best before’ or ‘use-by’ date like perishable food” and wonders if the parts required for specific integrated systems will be readily available in years to come.

Specialized, for example, has gone through four variations of integration on its road bikes (and even more when you factor in its Shiv TT / triathlon bike) – the Venge ViAS, third-generation Venge, Tarmac SL7 and now the Tarmac SL8.

That’s a lot of spare parts a brand needs to keep in the back catalogue to be readily available if and when riders require a replacement.

“If you are unfortunate and take a tumble, the parts will need to be replaced like-for-like,” Dubash adds. This wouldn’t be a problem on a conventional handlebar because you don’t need to necessarily replace exact parts like-for-like.

Proprietary parts can also come at an additional cost, compared to competitive aftermarket options. Remember, that’s before you factor in the increased labour bill for complex maintenance.

How would you improve integration as it is now?

Matt Millard is the workshop manager of Rides on Air, a bike shop in Wallingford, Oxfordshire that sells Trek and Merida bikes, among other brands. He has previously run workshops at Evans Cycles and Mountain Trax.

One way Millard suggests improving integration is by having any cables and hoses routed through a separate channel, rather than through the headset bearings. In theory, this would mean the lines could remain intact during a headset service.

The cables and hoses route through a separate channel

It’s a design some brands have already experimented with, such as the third-generation Cannondale SuperSix Evo.

The third-generation Trek Domane took a similar approach but routed the cables and hoses through a channel behind the headset bearings.

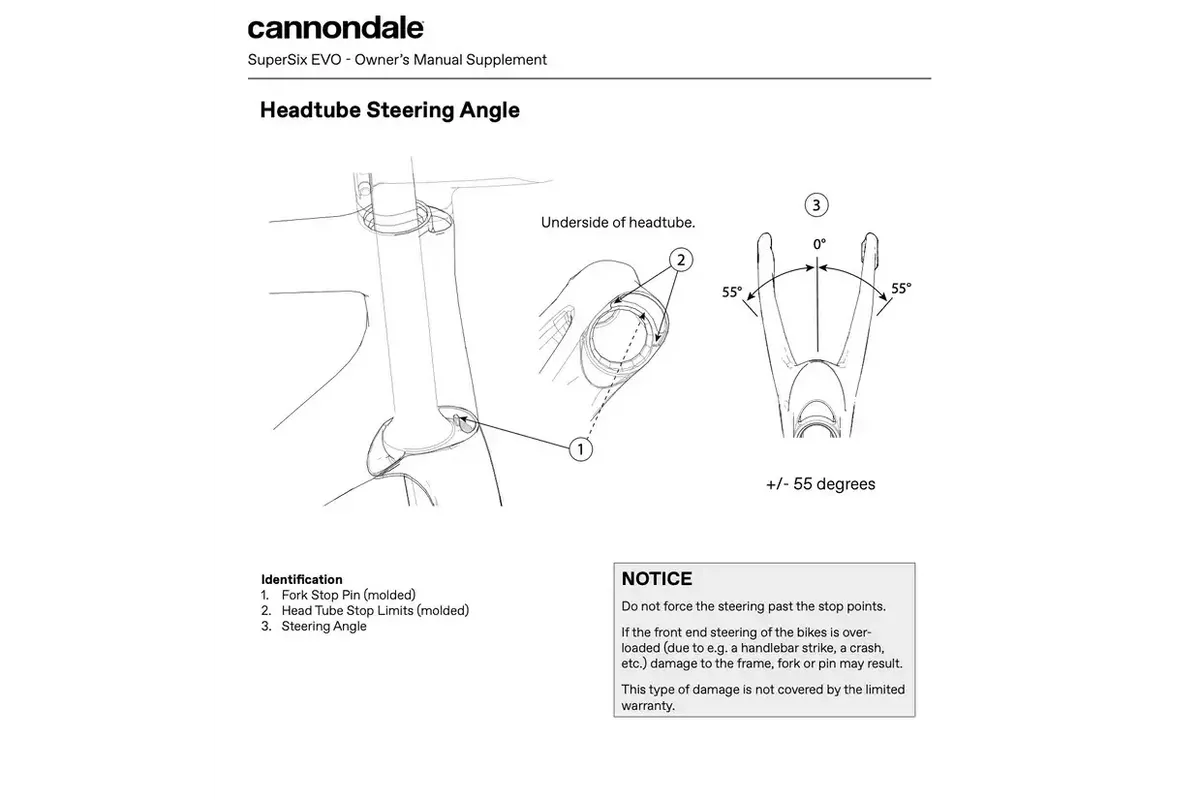

While this may seem like a logical solution, it has its drawbacks. Cannondale had to incorporate a steering stop into the front end of the bike to avoid the cables being effectively guillotined or the carbon fracturing if the handlebar was over-rotated.

Incorporating a separate channel also means the profile of the head tube needs to change, which means the top of the fork crown then needs to be sculpted to suit. This can lead to paint rubbing where the fork meets the head tube, or worse, fracturing if it is over-rotated.

Watkins suggests more space needs to be created for cables and that manufacturers need to “have a better consideration for how the bike can be disassembled and serviced throughout its life”. Having more space for the cables would result in less friction if a mechanical gear cable is used and, likely, an easier time for the mechanic.

“If nothing else, a lesser bill on the customer’s part having purchased a £10,000 machine might make them feel better about their purchase,” he says, emphasising what a wholly frustrating and miserable experience working on such bikes can be.

Hydraulic hose developments

Both Dubash and Watkins suggest improvements could be made to hydraulic hoses. Dubash advocates for a ‘plug-and-play’ option so you don’t need to cut the hose every time you undo the line.

He thinks it’s “a shame to trim back already optimally sized hoses” when they become “too short for safe operation”.

Barse thinks integrated systems would be better if brands specced “fully stainless bearings, or a bushing system, or what seems to be a hybrid like CeramicSpeed’s SLT”.

CeramicSpeed’s SLT (Solid Lubrication Technology) bearings are claimed to have very low-maintenance cycles and not wear out, and are backed by a lifetime warranty.

The system is starting to become more commonly specced on bikes from Factor, Canyon, Colnago and Pinarello – and for good reason. Given headset replacement is the chief concern of mechanics, if the bearings won’t ever theoretically need replacing, that can only be a positive.

Barse also suggests all systems should run full-length housing over the hoses, shift cables or electronic wires to eliminate any potential rattling.

Wallis would like to see more logical routing choices and better quality control. He says “most of the time lost on jobs comes from fighting with poor routing choices and messy / lazy manufacturing such as leftover bladder / epoxy inside of holes that snag a brake hose or cable”.

The holes are often only just big enough to fit the hoses and cables through and Wallis says he often has to “improvise a tool” when the ends of an internal cable routing guide are too large to fit through a hole.

He says he “wouldn’t mind a few extra grams on a frame with cleaner internal cable routing if it made maintenance easier”.

Should the bike industry adopt a single internal cable routing system?

Some brands, such as FSA, have tried to introduce integrated systems that can be adopted by numerous frame manufacturers. While FSA’s ACR system has seen moderate uptake from a handful of brands, including Argon 18, Bianchi and Vitus, it hasn’t ignited an integration revolution.

All of the mechanics suggested a single system was wishful thinking. Barse, Dubash and Wallis likened the prospect of a single internal cable routing system to other bike components that are rife with so-called ‘standards’, such as the infamous array of bottom bracket standards.

One reason why Watkins believes this won’t happen is because “brands have a look of their own they want to achieve”.

It’s a fair point, and brands would need to compromise their creative freedom if they were tied down to a certain design at the front end. This is supported by Barse, who says “if a [bike] manufacturer designed it, competitors want nothing to do with it”.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, Barse, Millard and Wallis all say they would be in favour of a single routing system if it ever happened, though. The benefits, Barse says, include giving mechanics a better “sense of the cost and time” to complete a job.

Indeed, the costs associated with the increased labour and replacement parts needed for integrated systems can come as a shock to unsuspecting customers and it can be very difficult to price a job, given the unknown variables before a mechanic begins their investigative work.

What are the differences in service costs for replacing headset bearings?

With the significantly increased labour time required to, for example, replace a headset bearing, you can expect the workshop bill to increase in tandem.

Millard suggests routine maintenance tasks can typically cost more than triple a standard headset service.

Dubash isn’t able to suggest a typical increase in cost because he charges by the time taken to do a job, rather than trying to predict this beforehand. He admits “Profitability goes out of the window to some extent in the pursuit of an end result I’m satisfied with”.

One only needs to look at Dubash’s Facebook page to understand his attention to detail – no stone is left unturned in his quest for servicing perfection. Most of his jobs tend to be a full service or rebuild rather than specific component replacements, so he says the exact cost is absorbed in the job’s final total.

Barse, Wallis and Watkins all charge an hourly rate, with Watkins saying it can’t be done by fixed cost anymore “unless you’re willing to lose money and take the hit”.

He notes “customers are generally understanding when this information is presented clearly up-front, though not everyone understandably takes the news well”. In fact, all of the mechanics note a transparent dialogue with the customer is always of benefit.

Watkins reminds customers their “top-end bike is designed for people who race them, who have parts replaced [by professional mechanics] before every event in some cases”.

As a result, it’s worth considering whether the performance benefits of a fully integrated bike – and particularly those with notoriously complex ‘solutions’ – are worth it against the increased running costs. Watkins likens this to owning a Ferrari, where “the cost of the car simply represents the initial deposit. Running and keeping it as new is what breaks you”.

Pre-sale education is key here, too. Barse says there is “a common theme of neglect by the sales floor to educate the customer on the actual cost of integrated systems”.

This can be a thorny issue, given that bike shops need to remain profitable to survive, and many brands are consumer-direct now anyway and thus bypass a traditional shop floor. However, the message for the customer remains the same – know what you are letting yourself in for if you do opt for an integrated bike.

Barse would also like to see improvements in brand documentation to help mechanics working on specific systems, such as “a universal library for service and technical bulletins”.

This is a view shared by Dubash, who says he spends hours trawling through manufacturers' documents and occasionally phones the component distributor if he’s faced with something he doesn’t have experience with.

If you weren’t in charge of maintaining your own bike, would you opt for integration?

Despite our mechanics’ general aversion to integration, both Millard and Watkins would own an integrated bike if money were no object, due to the clean aesthetic. However, Watkins is keen to point out this would also be on the assumption he “had no mechanical knowledge” of the disadvantages.

Wallis says he would also join the club if he was still racing, but doesn’t see the need for integration for any other cycling genre.

Both Barse and Dubash were less certain, with Dubash explaining, “the only way integrated systems make sense is if electronic shifting and hydraulic disc brakes are used”. However, he questioned whether those are things any of us truly need on a bike.

Barse says he “likes and appreciates some of the details a company can create for external housing stops or the fun challenge of clean cable routing for a tidy cockpit” but thinks many integrated bikes “look so similar to one another”.

Whatever your thoughts, integration is here to stay, but one thing’s for sure – there is a long way to go in ensuring easier maintenance for riders and mechanics.

Whether that’s in the form of a standardised internal cable routing system, headset bearings that don’t require servicing, simpler designs with clear literature for mechanics to follow, or simply better quality control, remains to be seen.