Aerodynamics represents pro cycling’s latest arms race and the quest to ride faster for no more effort continues with the evolution of the latest gear and expertise.

From ribbed skinsuits to turned-in hoods, WorldTour riders are seeking ever-more innovative ways to slip through the wind and reduce their CdA – or coefficient of aerodynamic drag, which, in simple terms, combines frontal area with the drag coefficient of the shape.

Two aerodynamics experts at the leading edge of the wind-cheating conversation are Dr Jamie Pringle, applied sport scientist and part of the setup at Vorteq Sports, a world leader in cycling aerodynamics, and Dr Xavier Disley of AeroCoach, the component and aero consultancy company.

“We’ve run 389 wind-tunnel sessions over the past four-and-a-half years with just shy of 300 individuals,” said Pringle at last year’s Science & Cycling Conference in Bilbao, lifting the lid on the company’s innovative practices and going on to highlight the potential gains for riders.

“At the WorldTour level, the average improvement in CdA is 6.6 per cent, which equates to a 25-watts saving. At Continental and domestic pro level, we’re looking at 6.9 per cent and a 21-watt saving. For top amateurs, it’s 9.9 per cent and a 29-watt saving.

“It’s over 600 hours of tunnel time. It’s a lot of effort. But it’s worth it as aerodynamics make a difference.”

It’s why we tapped Pringle up for his thoughts on the next-generation aero improvements that’ll be enjoyed by professional and recreational riders alike. Like Pringle, Disley has also attracted the attention of World Tour teams and riders because, in his own words, he’s a “nerdy aero geek”.

Here, Pringle and Disley predict the drag-saving trends for 2024 and beyond.

1. The aero domino effect

While bike brands and component manufacturers will often shout about the headline aerodynamic claims of their latest release, nothing exists in an aero vacuum. Increasingly, the need to consider all of the various parts of a rider’s ‘aerodynamic package’ will be front of mind.

“The concept of a ‘whole system’, in terms of aerodynamics, where many of the component parts interact with each other, will roll on,” says Pringle.

“That is, designing kit that considers what its effect is on the next piece, and making kit choices based on that. For instance, how a front wheel interacts with a frame; how a helmet interacts with a skinsuit; or even how the bike and rider interact with the person behind or in front.”

Arguably, the most cutting-edge example of the final point of this interactive concept is the Hope HBT track bike that British Cycling hopes will result in a glut of Olympic medals in the track cycling events at the Saint-Quentin-en-Yvelines Velodrome in Paris this summer.

“The wide front forks are predominantly to control the airflow that hits the rider’s moving legs, but also to reduce the interaction with the front wheel,” says Pringle.

“These effects are mostly for the rider themselves but there are potential benefits to others, too. In essence, if you can control the airflow off the back of one bike then the rider sitting in that wake will experience less drag, which pays off in the team pursuit.”

Having a rider sit close behind you offers an aerodynamic benefit to the rider in front – typically 2 to 3 per cent, but up to a 5 per cent saving in drag.

That’s well established and is also one of the tactical reasons why a rider should try to hang on at the back of the line for as long as they can in a team pursuit or team time trial, even if they can’t pull a turn on the front. The trailing rider is filling the low-pressure area behind the rider in front and reducing the overall high-to-low pressure differential that the front rider experiences.

“Whether the wide front forks add to this effect behind the rider, I’m not 100 per cent sure,” Pringle adds. “I expect most of the benefit of those is to the rider themselves; in other words, reducing their own drag.

"But it’s feasible that the rear stays could be shaping the flow so that the trailing rider effect is maximised for the rider. At least, that’s the design principle I’d be looking to achieve with it. It doesn’t matter if it’s a teammate or a rival – you’re going to get a benefit from someone sitting on your wheel so you might as well optimise and maximise it.

“All of this complicates the aero equation, of course, but it keeps designers and aero geeks in business because it’s a tricky puzzle to solve.

“We’ll probably see greater use of curious features on frames and forks (boundary layer ‘trips’ and turning vanes) designed to shape airflow for this whole system consideration, some of which will push the rules – think the split seatmast on the Look track bike – and maybe even force a rule change.”

2. The rise of aero drag sensors

Pringle has already detailed the considerable time, effort and expense that goes into data-led wind tunnel testing – but could a new era of real-world testing be on the horizon?

“I see greater integration of the on-bike systems that measure power and aerodynamics,” he says.

“Keep an eye on the guys at Body Rocket. They’re doing some good stuff, and I like the way they’re able to bring together a well-thought-out selection of sensors that help you understand how you ride the bike and how it and you perform together as a system and in your environment.”

Body Rocket is a device that fits onto your bike in the form of sensors on your seatpost, stem and pedals. Real-time aerodynamic drag force data is then beamed wirelessly to a Garmin bike computer, delivering in-the-moment feedback throughout the course of a training session or race, or as you play around with different positions, movements and gear.

After each session, you have a comprehensive picture of your aerodynamic data, which you can analyse to identify incremental improvements.

Aero sensors have flirted with the masses for a while, with the Notio Konect arguably the most well known, while Aerosensor also launched a new system last year.

The appeal of drag sensors to a greater audience, as per the first heart rate monitors and then power meters, has yet to happen for various reasons. The difficulty of interpreting data and their accuracy are notoriously difficult in the dynamic, chaotic real world.

Will Body Rocket launch this sector to a wider audience? Watch this streamlined space…

3. Clinchers are having an aero rebrand

“With the Paris Olympics and Paralympics coming up, there’ll probably be a big focus on track stuff this year,” says Disley of AeroCoach.

“Clinchers on the track are relatively new and, in some instances but not all, can be faster because of more aerodynamic shapes than tubulars.”

Clinchers are having something of an aero rebrand “but it isn’t the death of tubulars by any means,” adds Disley.

AeroCoach continually updates its rolling-resistance test page that evaluates the performance of tyres. Disley and his crew conduct the tests upon indoor rollers before validating the results outdoors.

The tests measure speed, power, system weight and the atmospheric conditions across all tyres. Each tyre is fitted to the same tubeless-compatible aluminium rim – external width 24.7mm, internal width 19.6mm – with the pressure standardised at 90psi.

The AeroCoach number-crunchers then calculate the co-efficient of rolling resistance (Crr) and power required to overcome rolling resistance at 45km/h. Low resistance equals a faster tyre.

Interestingly, the Veloflex Record tyres were the only ones to duck under 0.002 Crr with the clincher’s rolling resistance a seismic 0.000058 Crr faster than its tubular sibling. Marginal gains, indeed.

4. Speed-specific suits

“Individualisation will always be a theme that’ll feature strongly,” says Pringle. “You’ll likely see more kit choices – clothing mostly – filtering through product ranges based on different body types or performance scenarios.

“Tuning aero clothing to speed is a big one,” adds Pringle, "and some of the smaller manufacturers – for example, Rule 28 and Huub – have already put out kit that is optimised to different speeds.

“I think that trend will continue and grow, and while it will always be mainly a focus for the overall higher speeds of competitive racing, I think it’ll migrate into general riding like a lot of aero things do.”

Pringle’s forecast echoes that of his colleague and founder of Vorteq Sports, Rob Lewis OBE. In an entertaining and enlightening presentation at the Science & Cycling Conference in Bilbao, Lewis revealed how speed-specific suits are the future.

“At Vorteq, we currently take athlete shape, position and speed, scan them, optimise the drape and choose the right materials for the respective areas of the body,” said Lewis. “We then hit the wind tunnel, validate it and hopefully it gets a gong!

“In the future, we want to put the course in there, too. Take the Tour de France. You have 21 stages, which feature 21 different parcours with different weather at different speeds and even using different bikes. We could see a future where each rider would have a number of suits.

“On day one, the DS will report back that the wind’s coming in from the north-east, so you’d choose one suit. If it’s coming from the north-west, you might have a different suit.

“It’d be expensive – but worth it.”

5. Integrated convergence

‘All bikes look the same’ – we hear you in the comments! And, in many respects, you’re not wrong. Bar some notable examples – particularly on the track – the access to aerodynamic expertise, combined with the restrictions posed by UCI rules, means a lot of road bikes do look very similar.

The convergence of the aero and lightweight categories has also had a part to play here, says Disley.

“There’ll be a couple of new bikes out, certainly a nice time-trial bike at the Tour or just before, but from my perspective I think the integration of aerodynamics into more components and accessories is the thing to take note of – how everything these days has some kind of a nod to aero rather than very distinct (or even polar opposite) categories of aero vs weight in years past,” he says.

“More bike companies are leaning towards a do-it-all, aero-ish bike for racing rather than the wacky aero-at-all-costs options from years past. Maybe that’ll swing again the other way at some point – a real sprinter’s specific bike for the road would be awesome to see – but I can see things converging more and more.”

6. The exhaustive search for speed

“This is a small one but expect to see new helmets feature more specific venting that’s used for aero benefits not just cooling,” says Pringle.

“We’re seeing that many of the new aero helmets coming onto the market, both time trial and road, have a significant air intake and exhaust. If you know how to tame the flow, it can offer a significant performance advantage to channel air through the helmet and out to the base of the neck. And, of course, that tech filters down into all sorts of road helmets not just time-trial ones.”

One helmet that’s already made headlines this year is the Kask Utopia, used by Ineos Grenadiers – though those headlines haven’t come as a result of channelling, but ear shielding.

When hour-record holder Filippo Ganna dropped an Instagram post about the team’s new jersey and bike colourway, many instead focused on his head. The sides of the Utopia reached down the Italian’s cranium, covering the tops of his ears and arms of his sunglasses, leading many to speculate this was the latest drag-saver.

If Ganna can become an even faster Ganna then, well, he’s Ganna take some catching. (Sorry…!).

7. Blinded by UCI regulations

“Every time the UCI changes the regulations, there’s a shift in focus, so a lot is guided by that and it’s quite hard to predict,” says Disley.

“If they do away with the ‘14cm rule’, for example, we may see different hand positions being used in time trials by taller riders or a workaround there. But I think what they’ve done to outlaw puppy paws is good for safety and public perception of safety.”

A couple of explainers are needed, starting with that ‘14cm rule’. In 2023, the UCI amended its regulations for time-trial bikes, with the major change coming in the form of revised reach and aerobar dimensions for riders of different heights, broken down as:

- Category one riders, up to 179.9cm tall, can have up to 800mm of reach, which is the distance between a vertical line through the bottom bracket and the tip of the aerobar extensions

- Category two riders (between 180 and 189cm tall) can have a maximum of 830mm reach

- Category three riders (over 190cm tall) can have up to 850mm of reach

This then leads to the regulations relating to the differing amounts of armrest pad to shifter height, because category one riders are permitted a maximum difference of 100mm, category two 120mm and category three 140mm. Banish this rule – unlikely anytime soon – and a greater number of hand positions could result in easy wins.

As for 'puppy paws”, this is when riders draped their wrists across the bars to flatten their backs a la TT position. Understandably, the UCI saw this as a dangerous move.

The latest aero hack to fall foul of UCI commissaires is the trend for turned-in brake levers, adopted by riders to create a smaller frontal profile but now banned by cycling’s world governing body.

The rule update was brought in to control the extent to which riders could have their hoods turned in. The UCI cited safety concerns, claiming it can be harder to grab your brakes when needed, and also said it has evidence that extreme angles can damage carbon handlebars.

In plain terms, the new UCI rule says the hoods must be roughly in line with the line of the drops. If you have a bar with straight drops, the hoods will have to be roughly straight too.

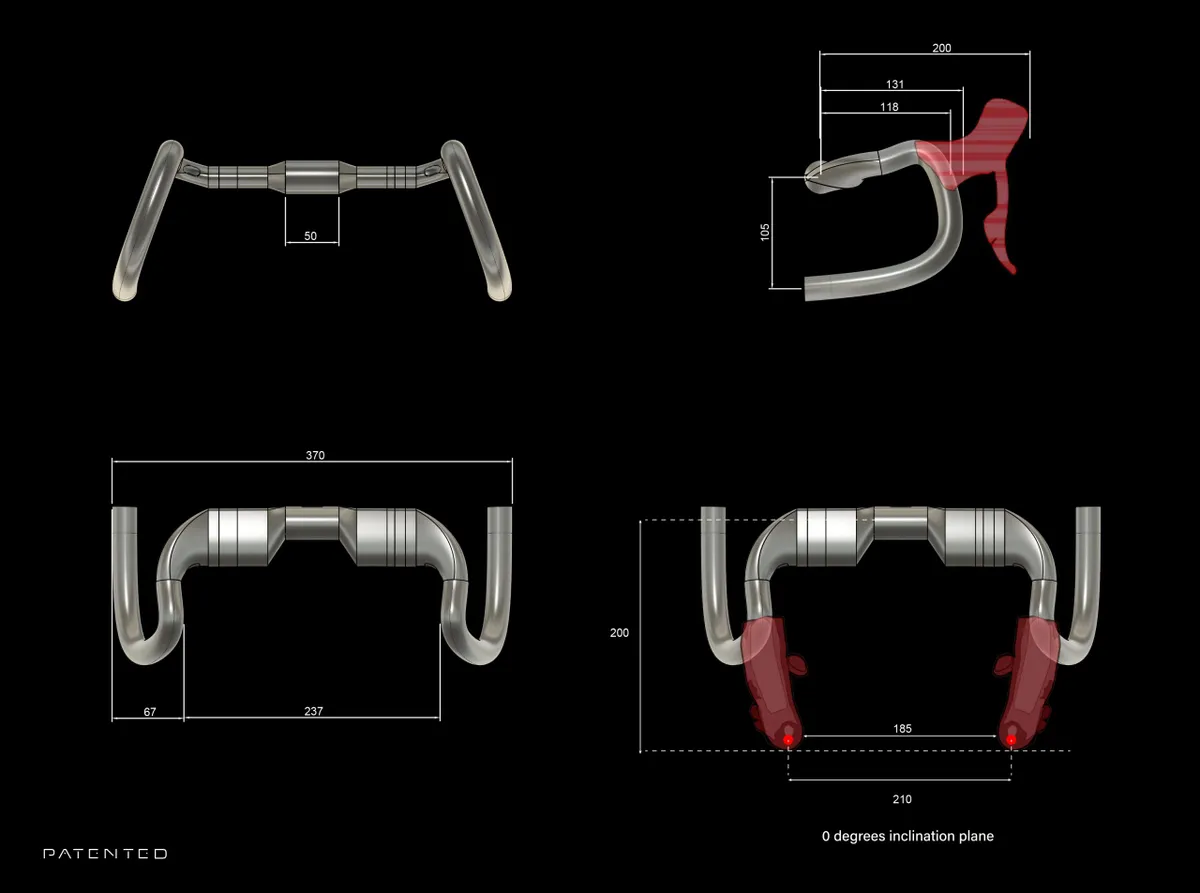

The clever move, however, is to use a bar with flared drops. This way you can still angle your hoods in while keeping them in line with the drops. Thus, a rider with a flared bar will be able to have a narrower position at the hoods, potentially making them more aero.

Will we see a new wave of handlebars designed to skirt UCI rules? The Ashaa RR Carbon is one extreme example, measuring just 21cm between the hoods (and 18.5cm at the narrowest point), with the drops then measuring 370mm at the widest point.