I hastily scribbled the Silk Road Mountain Race at the top of my bucket list soon after its inaugural edition finished in 2018.

I have followed the race obsessively since, poring over race photography of riders on fully loaded rigs, silhouetted against vast and dramatic landscapes.

The panoramas seemed surreal, the riding conditions looked remote and hostile – it looked like a raw, unsanitised adventure, potentially dangerous and challenging.

I was captivated by it and in the years since its inception, I have worked towards getting myself to a place where I could legitimately say I had a good chance of getting around the 1,900km route.

For all the obvious reasons, not many things have been ticked off bucket lists these past few years. The 2022 Silk Road Mountain Race, returning for its fourth edition, promised the perfect antidote for one too many summers on the sofa and a chance to fulfil a goal that’s occupied a lot of daydreaming and planning for me.

With my application form submitted and accepted, thoughts quickly turned to the kit, equipment and most importantly the bike I would use for the race.

I spent a long time researching the route, reading blogs and reviewing various bike options and setups, with a mix of excitement and nervous apprehension for the challenge ahead.

Josh’s Silk Road Mountain Race

The horse: Surly Karate Monkey, a steel flat-bar mountain bike, with Hunt Enduro 27.5in wheels, Maxxis tyres, Shimano Deore and Sun Race groupset components, and Apidura bike bags.

The course: The Silk Road Mountain Race – 1,900km of Kyrgyzstan’s toughest tracks, with 37,000m of vertical elevation over high mountain passes.

The goal: To get around!

The Course – the Silk Road Mountain Race

The Silk Road Mountain Race is the brainchild of Nelson Trees, who is also the organiser behind the Atlas Mountain Race in Morocco.

After living for a time in Shanghai, Trees cycled to Paris from there in 2013. He spent lots of time on that trip in Kyrgyzstan and knew he would return to explore more of the country’s wilderness and opportunities for remote and adventurous riding.

With a taste for unsupported bike races, fuelled by riding the Transcontinental Race a few times, Trees returned to Kyrgyzstan, scouted a route and launched the Silk Road Mountain Race with guidance from the past Transcontinental race director and ultra-cycling legend, Mike Hall.

As a result, the Silk Road Mountain Race is inspired by many of the ethical principles and rules of the Transcontinental Race and has an unwavering ethos for unsupported racing.

Now, the race has established a reputation, community and following and is known around the world as one of – if not the toughest – unsupported races on the calendar.

The ultra-distance event is fully unsupported. Riders have to carry everything they might need to complete the long route, including sleeping kit, appropriate outdoor clothing and necessary electronics for night riding and navigation.

The terrain is as brutal as it is beautiful and large sections of the race take in extremely remote and unforgiving landscapes. The route has 37,000m of climbing and rises above 4,000m, so dealing with the effects of cycling at altitude is a major part of the race.

Food can be purchased along the way, but resupply points are often a few days' riding apart and the remoteness of the locations limits what you can get. This makes careful planning of fuelling and hydration essential.

To add to all of this, the temperature can reach 40˚C in the valleys and drop below 0˚C on the mountain plateaus. You can experience these two extremes within 24 hours.

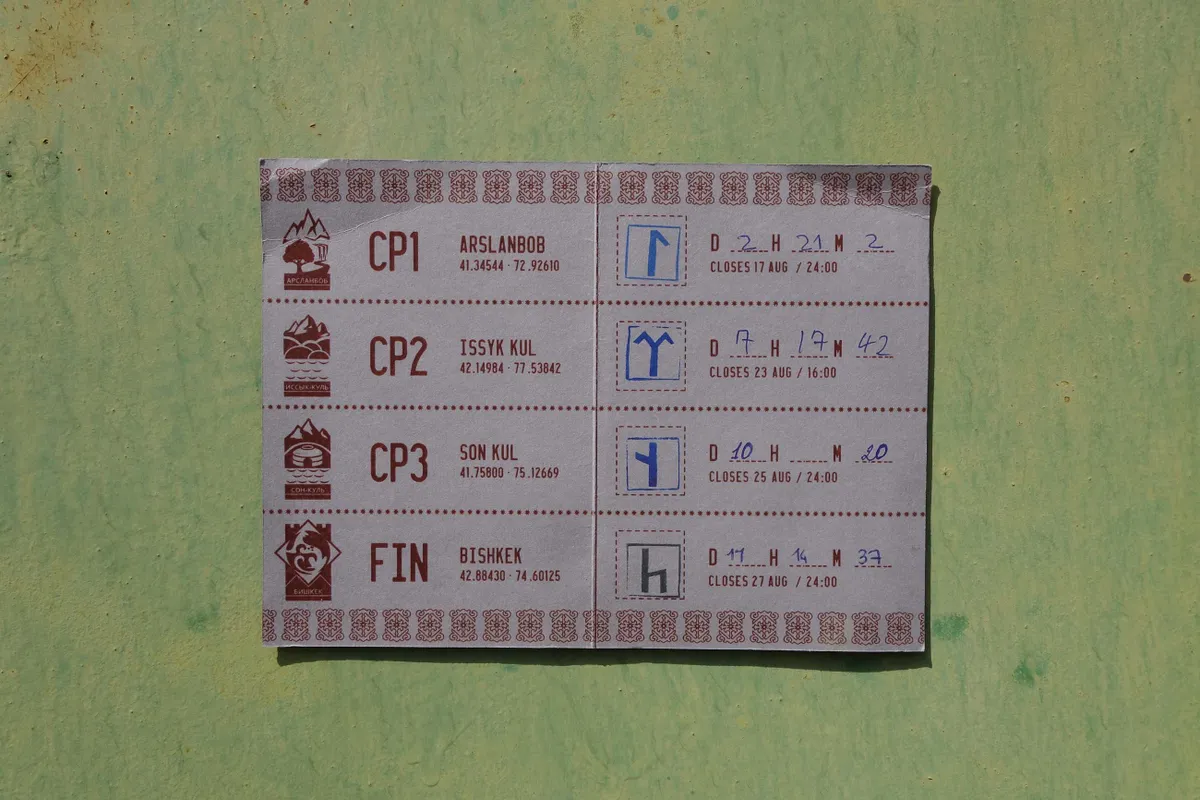

There are several checkpoints as part of the route and there are cut-off times for each of these that riders have to beat if they wish to finish as part of the general classification.

The cut-off time for the whole route is 14 days. However, the winners often finish in just over half this time, while most take between 10 and 12 days.

The race is quite well known for having a high dropout rate. On average, only half the riders who line up at the start line make it through the whole race.

The Horse – Surly Karate Monkey

When considering what bike to use for the Silk Road Mountain Race, speccing a suspension fork seemed like a good idea, as did flat bars. I also found myself balancing ideas for the bike with the reality of where I live in London.

Somehow, I couldn’t justify buying a full-on mountain bike for the race, when afterwards I’d mainly be riding it on canal towpaths or weekend gravel rides. I could put up with some discomfort on the race, I told myself, if it meant getting more use out of the bike.

Getting a Surly had also been on my mind for nearly as long as I’d contemplated throwing my chapeau in the ring for the race.

I’d read a lot of reports where Surly bikes had been used for round-the-world trips and big adventures. Their reputation for being extremely reliable, durable and suitable for a wide range of riding styles appealed to me.

The Surly Karate Monkey seemed to tick all the right boxes. It has huge tyre clearance, can fit different-size mountain bike wheels, has loads of lugs for bottle cages, secure storage and fork mounts, and I can still upgrade to a suspension fork if I wish.

On top of this, the geometry feels both comfortable and nimble, and the concerns I had about weight were generally unfounded.

My bike weighed around 11.5kg. It likely weighed a fair bit more than most of the bike builds on the start line of the Silk Road Mountain Race. But my days of being a weight weenie are long behind me, given I tend to strap luggage to every square inch of frame space these days.

It’s very easy to make back the few kilos you’ve added for the extra reliability of having a bomb-proof steel frame with some good bags and a carefully curated kit list.

The airport weigh-in on my way to Kyrgyzstan revealed the bike and my kit to be just shy of 30kg. This is far from lightweight, but everything I had with me felt necessary to survive the extreme conditions of the race.

Shimano Deore

Over the years of riding long distances, both on the road and off – often in challenging weather over routes I’ve not spent enough time planning – I’ve realised I simply can’t afford top-end components on bikes.

As I live in a second-floor flat, cleaning a drivetrain after a ride feels like more hassle than it's worth, but this lax approach regularly trashes cassettes, bottom brackets and brake pads. With that in mind, I pretty much only ever use Shimano 105 for road and Shimano Deore for mountains.

Through trial and error, I’ve found these to be the most reliable and durable components. They don’t break the bank or make a bike feel overly clunky.

For the race, I used a SunRace MX80 11-speed 1-50t cassette paired with a Shimano M5100 Deore 32t crankset for getting over steep climbs.

Braking and shifting were all courtesy of Shimano Deore and I had 160mm rotors front and back.

Hunt Enduro wheels with Maxxis tyres

The one area where I do tend to spend money to upgrade components is on the wheelset. Broken spokes and ripped tyre walls were my main concern in the lead-up to the Silk Road Mountain Race.

I spent a long time nervously reading reviews of tyres and wheels, as well as looking at the setups past racers had chosen.

In the end, I opted for Hunt Enduro 27.5in mountain bike wheels and Maxxis Crossmark II 2.25in tyres.

I have ridden Hunt 4 Season wheels for nearly 40,000 kilometres without incident, so figured I should stick to a brand I know for this.

The Enduro wheelset is built with 32 triple-butted and reinforced spokes for the rear wheel. There are only 28 on the front, but this seems to be the industry standard these days and, after getting a few quotes for a bespoke build, the decision to buy ‘off the shelf’ seemed obvious.

I also take a lot of comfort in the research, development and testing Hunt seems to do within the field of ultra-racing. I’m always drawn to bike brands that put their focus on this style of riding because badly designed parts or poorly built components are quickly found out.

I set the Maxxis Crossmark II tyres up with Stan's tubeless sealant, and this proved a perfect choice. I had zero punctures over the hardest 1,800km I’ve ever done. Along with Vittoria Mezcals, the Crossmark II tyres seemed to be the most popular choice for endurance racing by a long way.

Grips, bags and navigation

I used Ergon GP2 mountain bike grips with integrated bar ends and added some cheap aero bars from Prime components to give me more options for hand positions.

The lights were from Alpkit and I used a Garmin eTrex 32 mounted on the stem for navigation.

Other additions were a pair of Blackburn fork cages to fit some expedition fork packs from Apidura. The rest of the luggage was also courtesy of Apidura. The brand’s Backcountry range allowed a total carrying capacity of 37 litres spread evenly across the bike.

Josh’s kit list

With big temperature swings on the cards and the unpredictability of high mountain weather being a major concern, my kit list was fairly extensive. I want to thank Apidura and MAAP for their support with this.

Apidura Backcountry 11L handlebar bag

- Nature Hike tent – ground sheet, outer (no inner), poles and six pegs.

- MAAP Alt_Road Haelo jacket

- MAAP Alt_Road Polartec long-sleeve T-shirt

- Rab beanie

- Spare bibs

- Spare socks

- Helly Hansen Lifa leggings

Apidura Backcountry 6L saddlebag

- Therm-a-Rest NeoLite sleeping mat

- Rab Neutrino 600 sleeping bag

- SOL Emergency foil bivvy

Apidura Backcountry 6L full frame bag

- Arc'teryx Beta LT jacket

- Marmot double-zipped waterproof trousers

- Sealskinz mid-length waterproof socks

- MAAP Alt_Road Thermal Jacket

- MAAP Base arm warmers

- MAAP Base knee warmers

- Rab Cresta Gore-Tex gloves

- Extremities Tuff Bags Gore-Tex overmitts

- First aid kit

- Passport

- Essential documents

Apidura Backcountry 1.8L top tube bag

- Anker PowerCore 26800 battery pack

- Alpkit 5000mA backup battery packs x2

- Petzl Tikka XP head torch

- USB wall adaptor

- Micro USB charging wire x2

- iPhone charging wire

- USB-C charging wire

- Headphones

- Suncream

- Toothbrush and toothpaste

- Chamois cream

- Cash and card

Apidura Backcountry 1.8L down tube bag

- Topeak multi-tool

- Inner tubes x2

- Park Tool tyre levers

- Park Tool tyre boot

- Park Tool adhesive patches

- Park Tool mini chain tool CT-5

- Lezyne Pocket Drive mini pump

- Lezyne tubeless tyre plug kit

- Shimano magic chain links x2

- Muc-Off mini dry chain lube

- Cable ties

- Spare gear cable

- Spare brake pads x2

- Spare cleat x2

- Fiber Fix spoke repair kit

- Gorilla tape (wrapped around pump)

- Needle & dental floss (for sidewall gashes)

- Spare batteries (AAA and lithium AA)

Apidura Expedition 1.8L Fork Bags

- MSR Windburner 1l stove

- Gas canister, 230g

- Snow Peak spork

- Swiss army knife

- Platypus 2l water carrier

- Windproof matches

- Lighter

- UV water filter

- Peanut butter

- Instant noodles

- 3-in-1 coffee sachets

Apidura Hydration Race Vest 7L

- 2L water bladder

- Garmin In reach tracker attached

- Sony RX100 camera

The Silk Road

The weeks leading up to the Silk Road Mountain Race flew by. The list of jobs, agonising over details and tweaking my setup never ended, and I busied myself in packing and repacking the bags far too many times.

To make things that bit more interesting, the race began at midnight. Of course, in the run-up to the start, I hadn’t managed to sleep – a mixture of nerves and apprehension had seen to that, and I was far from relaxed.

One long caravan

If anything, I was relieved when the time finally came to turn the pedals. Pretty soon after a police escort out of the southern city of Osh, the lights of the competitors who had been drawn to this race from all over the world stretched out as far as the eye could see, snaking up into the darkness of the nearby hills.

It was one long caravan, screeching, whirring and ticking, with hundreds of unique journeys illuminating one single route. Not all who set out along the route finished, but the severity of the terrain, the scale of the landscape and the extremes of the climate would leave their mark on all those who dared.

It was difficult not to draw parallels with the traders who sought out the riches of the Silk Road, often at great personal risk.

Golden plains and boulder fields

I would think often of these romantic notions throughout the ride, as I traded coins for peach ice tea, sought refuge from herdsman and dodged nefarious drunkards and bandits through some of the larger towns. I cast myself as an early explorer and the horse beneath me, a thoroughbred American steed.

The first three days proved difficult as I adjusted to the demands of the race. Food was harder to come by than I imagined and in the wide, exposed valleys the midday heat was at times unbearable.

It always seemed that the beauty of the landscape, however, was proportional to how hard the riding was and I only had to take myself out of the race mentality to gain some perspective on my situation. There are certainly worse places for glycogen-depleted tantrums than vast golden plains with eagles soaring overhead.

The route was spectacular and ever-changing. Within a morning, you could be picking your way through moon-like boulder fields and after a descent that wouldn’t look out of place in the Swiss Alps be zipping down sandstone gorges with deep, red rock faces on either side.

A daunting profile

A substantial part of the challenge of the Silk Road Mountain Race comes from the extreme amount of climbing.

While climbing is perhaps one of my stronger traits as a cyclist, the sheer amount of ascent spread over the distance of the race is quite a daunting elevation profile, even for the hardiest of grimpeurs.

Added to this is the fact that a large proportion of this profile jumps over 3,000m, even hitting 4,200m at one point.

My drivetrain, with its 32-tooth front chain ring and dinner-plate sized cassette, gave me a gear ratio of 1.56. While this wasn’t the biggest in the race, it felt more than enough for the gradients of the route. When you’re up to such ratios at altitude, hiking isn’t too much slower.

<![CDATA[//><!]]>

Journey’s end

By the time I reached the finish line in the country’s capital, Bishkek, I had been on the road for 11 days, 14 hours and 37 minutes. It was enough to put me in 25th place and 18th within the solo category. This year, 83 finished out of a total of 151 starters.

I was seriously pleased by the result and even more so to be finally out of the saddle.

I’m proud of finishing and will duly frame my completed brevet card for the bathroom wall, but what I will take away from the Silk Road Mountain Race is so much more. I’m only really just beginning the task of processing the ride; its drama and scale, its imagery and emotion. Yet I am already certain it will define me for a very long time.