Against better judgement, I cannonballed into the deep end of gravel racing last weekend at the Dirty Kanza 200. We're wrapping up a video feature, 'The Road to Kanza', about the preparation of bike and body for 200-plus miles of gravel, but I thought I'd share my gear selections here in the spirit of BikeRadar's Horse for the Course features.

If you are getting into gravel racing, perhaps some of this will be helpful. If you think gravel racing is stupid, then hopefully you can enjoy some of my epic fails detailed below!

- The course: Dirty Kanza 200, an unsupported 206mi, 10,000-vertical-foot gravel slog

- The equipment goal: A comfortable race bike with tires that can withstand Kansas' flint gravel, and the means to carry a small truckload of water

- The horse: Trek Checkpoint SL 6 with ENVE G23 wheels and Schwalbe G-One 38mm tubeless tires

- The winning bikes of the 2018 Dirty Kanza

- The weird and wonderful of the 2018 Dirty Kanza

- 206 miles of Dirty Kanza: ENVE G23 first ride review

You are responsible for you!

Part of the deal with gravel racing is that it's unsupported. Race bibles and websites often contain the phrase, in boldface and all caps, "YOU ARE RESPONSIBLE FOR YOU!" Warnings about not retrieving riders from the course, no matter the mechanical situation, are commonplace. It's a little intimidating, and not entirely true.

For one thing, gravel racing has checkpoints where you can restock from bags you send ahead. Folks in the checkpoints can help you out. Also, if there is an outright emergency, an ambulance can and will come get you. That said, it's a far cry from an office-park crit where you can drop out at any time and coast back to your car.

Part of the fun and challenge is preparing your bike and gear. On one hand, you can bring all the things. On the other, there is the temptation to travel light. I tried to split the difference.

Stock the checkpoint bags: fresh CamelBaks, food and supplies

Our upcoming Road to Kanza video feature is supported by CamelBak, which provided us with several Chase Bike Vests and insulated Podium Dirt Series bottles with Mud Caps.

Being a pretentious roadie, I am philosophically averse to wearing a backpack when riding a dropbar bike. But I tried the Chase vest at a gravel camp with some other journalists and then used it for the Land Run 100, where it absolutely made the difference for me by being able to blaze straight through the 50-mile checkpoint and stay with the lead group, most all of whom took musette hand-ups on the fly to restock on water bottles.

The Chase vest sits high on your back, so you can still get to your jersey pockets. And there are pouches on the front where I packed in gels and blocks and peanut butter crackers and other snacks.

I packed three Chase vests for each checkpoint, with Skratch in the 50oz bladders, snacks in the chest pouches and Podium bottles in the external pockets for a one-grab restock.

I also put extra tubes and CO2 cartridges in the checkpoint bags, plus sunscreen and big chunks of carrot-cake bread my daughter Stella baked.

Soften up the bike, pack in flat-fixings and pray for good luck

The bike was pretty straightforward albeit swanky: a Trek Checkpoint SL 6 with its bump-gobbling IsoSpeed decoupler, huge clearance and more mounts than I know what to do with. (Actually, now I do...) Although the stock Montrose Pro saddle is comfy, I went with the Specialized Power Elaston because 206 miles, man.

I swapped out the alloy bar for a Bontrager IsoCore model that has a layer of elastomer in between carbon plies, with foam under tape on the tops. I added a little extra foam up near the stem for my forearms, expecting to spend at least some time hunkered down in the wind.

ENVE hosted a few of us for the weekend, providing assistance in the checkpoints, which was huge — Bo VanBrocklin and Shelby Vandersteen, you guys are heroes — plus sample sets of the new G23 gravel wheels.

Despite my friend and Kanza vet Neil Shirley giving me the high eyebrows on this, I went with Schwalbe G-Ones set at 36/38psi, and loaded nervously with approximately 3–4 liters, er, ounces, of Orange Seal a piece.

I filled the canister under the down tube with a tube, a CO2, breaker and lever. In the saddle bag went another tube, two more CO2s, a multi-tool, a chain connector link and a patch kit. A Lezyne pump on the bike and a good-luck wish completed my mechanical reinforcement package.

Stupidly, I used Lilly Lube, which works great in the dry. Not so much after rain and multiple creek crossings.

Bad luck compounded by dumb decisions and incompetence

One cool feature of gravel racing is the mass start. After a 30min lightning delay in the rain, we rolled out, about 1,000 strong. Two ENVE friends were taken out by a dumb crash inside the first 10 miles as we zoomed along four-wide. (They rallied back to finish top 30.)

What commenced was the most pathetically long flat change in the history of bicycle riding

My plan was to stay with the front group as long as possible. I don't know much about gravel racing, but I do understand and revere the draft. Speeds aren't what they are in road racing, but physics is physics: less wind in your face means less work for your legs.

The forecast called for a cross-tailwind for the first 100 miles, then pretty much a block headwind of up to 22mph for the last 100. I was eager for company!

The course is littered with short drops and rises, often with creeks or cattle guards at the bottom transition. At one such section at about mile 20, my friend Chris Case flatted in front of me, and a split second later I heard my tire go. Rats.

What commenced was the most pathetically long flat change in the history of bicycle riding.

My coworker Josh Patterson had given me a Dynaplug system the night before, which seals small punctures with a plug and inflates the tire. I tried this. It failed.

I then realized I should turn on my GoPro to capture my fumbling. Once the camera was on, I retuned to the tire to find the tear and boot it. I could not find the tear for the life of me. Meanwhile, hundreds and hundreds of riders streamed past.

I pulled off the mud-caked, sealant-filled tire and ran my hand quickly around the inside, looking for the hole. No dice. I slowly traced my hand around the inside, over and over. Nope.

I decided I had to inflate a tube inside the tire to find the hole, then deflate and boot it. I got a tube in and tried to use the Dynaplug breaker to inflate it, but realized as the air blew everywhere but into the tube, that would not work. So I got the pump off the bike and looked at Chris, who was also still fumbling with his bike; what the heck was taking him so long?!

As I pumped up the tube with a gagillion strokes and finally found the tear, Chris came walking up the hill. His Dynaplug attempt, also in a G-One, had also failed. So he proceeded to break off a valve stem inside his pump, rendering it useless.

At this point the mood switched from panicky frustration to comedy. The race was gone. I handed Chris my pump and opted for a nature break.

He fixed his bike and got going. After sticking a GU wrapper in as a boot, I pumped and pumped and pumped on my tube. Nothing. I must have pinched or otherwise damaged that tube after pumping it the first time to find the hole.

So out that came and in went the second and final tube, and the third and final C02 cartridge. Luckily, that worked. All that was left was to clean up the supplies I had strewn like a picnic all over the ground.

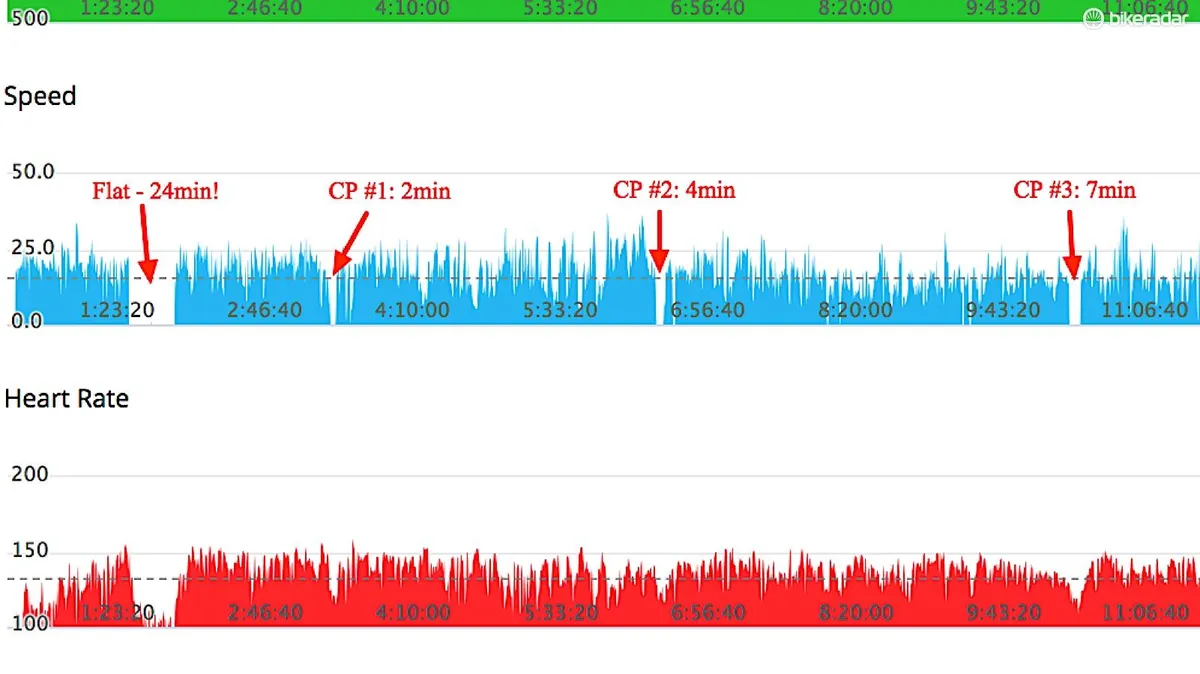

Twenty-bleeding-four minutes later, I was rolling again.

Brother, can you spare some pickle juice?

It wasn't until the first checkpoint that I saw Chris again, by which point my drivetrain sounded like a flock of wounded seagulls.

Having a pro pit crew to lube the chain and hand off the CamelBak vest was huge. I was going again in two minutes.

With 150 miles still to go, Chris and I had some catching up to do. We caught up more on each other's lives than we did on the long-long-gone front group, but hey.

Chris had a single aerobar extension on his bike, which he dubbed the narwhal, without an arm rest. The more we battled along as a two-man time trial squad in the wind (100 miles of headwind, people), the more the narwhal seemed like a good idea.

The race is long enough for multiple good and bad patches to come and go. And for multiple little groups to form and disperse. I met people from all over.

At the second checkpoint, I had a couple of pickle slices from a jar the ENVE boys had set out. I should have chugged the whole jar — and put another jar in a pack.

Stupidly, at the third and final checkpoint I opted to just take two bottles and forego the CamelBak. My small brain was thinking, 'Hey, it's just 40 miles. Two bottles is plenty.' Um, no.

One of the many cool things about Dirty Kanza I found was the plethora of ordinary folks out in the seeming middle of nowhere with huge stacks of cold water bottles. Not race officials or race volunteers, just regular people. Some in front of their houses, and some sitting in their vehicles at dusty crossroads. These people are angels. I must have grabbed 10 bottles throughout the day.

Around mile 175 I felt a cramp coming on, and gingerly tried to nurse it by barely pedaling with that leg. By mile 180, it locked up a few times, causing me to lose the wheel of a few groups.

At one point, with on-bike stretching not shaking it, I wobbly dismounted and started walking. Walking, it turns out, isn't the ideal way to go fast in a bike race. But it was a nice change of pace. Why did I forego that last CamelBak and extra salt again?

Checklist of what worked great

- Trek Checkpoint Sl 6 — No complaints!

- Bontrager IsoCore bar with foam padding — Happy hands after 13 hours ain't easy

- Ultegra hydro group — Shimano stuff just works. And works. And works

- Stages Power R Ultegra — How do I know if I'm having fun without data?

- Garmin 1030 — After using battery save for the first 100 then normal power for the rest, I still had 48 percent battery at the end

- ENVE G23 — Light, wide and not too stiff

Checklist of what needs to be improved

- Tires / luck — Tires are the question. I hemmed and hawed between Maxxis Ramblers and G-Ones. On one hand, the early flat for Chris and I fundamentally changed our race. But on the other, we both rode the next 186 miles with no problem. Other riders on other tires had three, four, five and six flats on the day. Some dropped out with destroyed tires. I went with the G-Ones because they feel so supple and fast. The men's and women's winners were on Ramblers.

- Hydration — More. Just more. The Checkpoint can be configured for three cages inside the main triangle (plus the fourth below). I regret not adding that third. I also regret not using a CamelBak for the fourth leg (it's only 40 miles...). And I regret not taking on more salts all day long. Cramps suck.

- Sodium/electrolyte consumption — See above. More pickles and chips next time.

Why the heck would you do this? And would you do it again?

I made it back to downtown Emporia 13 hours after I started. That is certainly the longest time I have ever spent on a bicycle.

My friend Nick Legan was the first person I knew to have done the Dirty Kanza. That was at least eight years ago. I made fun of him. Hiding in ditch way out in a field as a storm blew over, only to ride and ride and ride some more? It sounded horrible.

And yet, here I am, already plotting about how I am going to reconfigure my run at the silly thing next year. More bottles, more rubber, and more pickles. Definitely more pickles.

See you in Emporia?

p.p1 {margin: 0.0px 0.0px 0.0px 0.0px; font: 11.0px Calibri} span.s1 {font-kerning: none}