While Mathieu van der Poel won his first Paris-Roubaix last weekend, the great Fabian Cancellara won the last of his three cobbles just over a decade ago.

Though the fundamentals remain the same, road bike tech has come a long way in the meantime.

Spartacus won aboard a Trek Domane – an endurance road bike designed specifically to tame cobbles.

The Flying Dutchman on the other hand, rode a Canyon Aeroad CFR – the same aero road bike he recently piloted to victory in Milan-San Remo, with only a few minor modifications.

With that in mind, let’s break down each winning bike and look at what has changed in the past 10 years, and whether anything has stayed the same.

Frames – endurance vs aero

As already noted, Cancellara, who was part of the Radioshack-Leopard-Trek team, rode a Trek Domane 6-Series – an endurance road bike made from carbon fibre.

Those with good memories will know he used the same bike (with a slightly different setup) to win his second Tour of Flanders the previous week.

The Domane 6-Series was the American brand’s first iteration of a Classics-specific bike, launched in 2012, and, as such, employed a number of features designed to help smooth out rough roads.

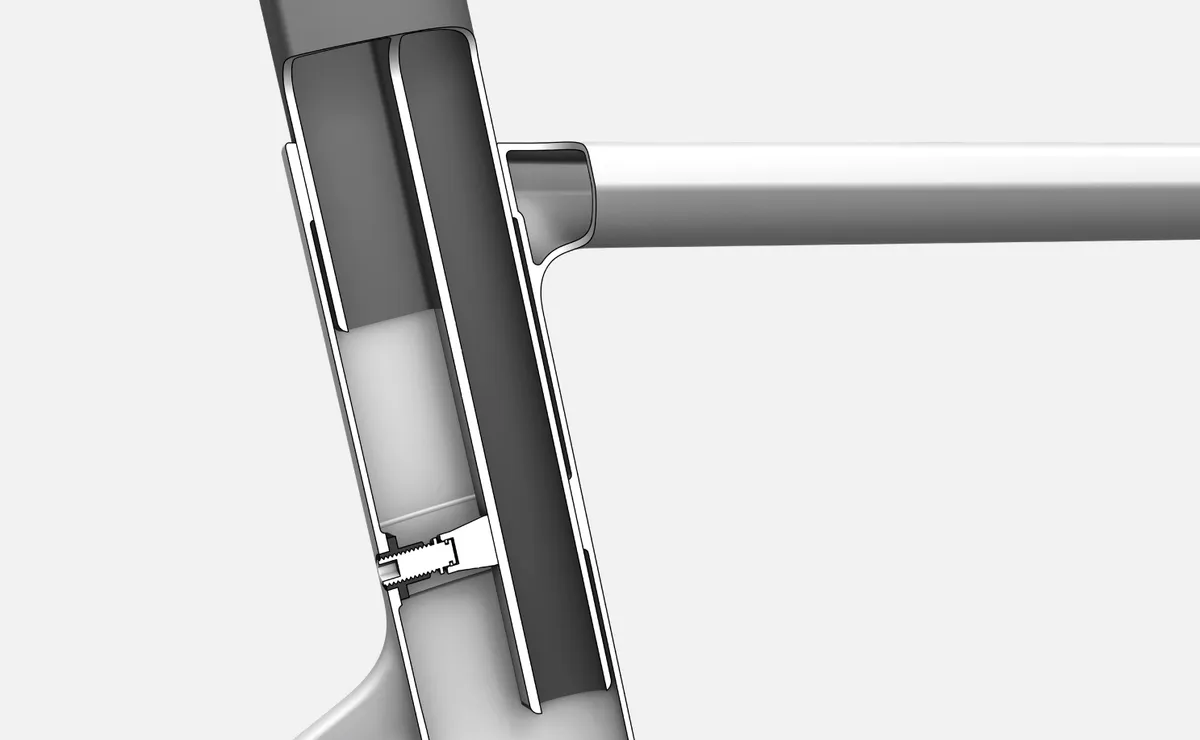

One of those was Trek’s IsoSpeed decoupler system, which debuted on this bike and allowed the seat tube to flex independently of the top tube, via a bearing pivot at the seat cluster.

At the time, Trek claimed it improved comfort by up to 50 per cent compared to the Madone 6-Series SSL Cancellara and his teammates had used previously.

And while the pro-spec Domane used Trek’s aggressive H1 fit geometry (which enabled pros to get their favoured long and low riding positions), the handling emphasised stability, with an elongated wheelbase and a slacker head angle compared to the Madone.

Tyre clearance on the Domane 6-Series was officially capped at 25mm (which, quaintly, was considered wide for road bike tyres at the time), though James Huang noted at the launch that “by visual inspection, 28mm tyres will easily clear.”

Claimed weight for a Domane 6-Series frame was a fairly impressive 1,050g, no doubt helped by the fact it was a bike designed for rim brakes and used Trek’s infamous BB90 press-fit bottom bracket system.

In contrast, van der Poel’s Canyon Aeroad CFR was designed, first and foremost, for speed.

Launched in 2021, the Canyon Aeroad CFR uses deep, truncated aerofoil carbon tubing throughout and, like almost every other modern road racing bike, uses hydraulic disc brakes.

The Aeroad has clearance tyres up to 30mm wide, officially, though in practice there’s room for a little more here too.

Other than that, stock Aeroad’s make only relatively minor two concessions to comfort – dropped seat stays and a special seatpost (which clamps low down at the rear of the seat tube to allow it to flex).

I say ‘stock Aeroad’s’, though, because MVDP’s bike is actually a prototype which features a slight modification to this area – the seatpost clamp has been moved to a more traditional position on the top tube.

Given Canyon says the low clamping position is crucial to allowing the comfort-enhancing seatpost to flex, we can likely surmise MVDP’s bike doesn’t take advantage of this feature – or at least not to the same extent as stock bikes.

Almost every rider on van der Poel’s Alpecin-Deceuninck team opted for the Aeroad CFR.

The only deviation, as far as we know, was Gianni Vermeersch, who rode his 2022 gravel worlds-winning Canyon Ultimate CFR (albeit with road tyres in this race).

The claimed frame weight for the Aeroad CFR is 915g, although the more crucial stats for this bike naturally focus on its aerodynamic efficiency.

While we’ve clearly not seen any wind tunnel comparisons between a Trek Domane 6-Series and a Canyon Aeroad CFR, the eyeball test would suggest the modern bike is significantly more aerodynamic.

Groupset & gearing – RIP mechanical groupsets

While the differences here are more subtle, a closer look reminds us that things have also changed fairly significantly when it comes to gearing since 2013.

Both Cancellara and van der Poel used top-of-the-range (for their time) Shimano Dura-Ace components, with gearing focused on a fast, flat race.

MVDP used a 12-speed, Shimano Dura-Ace Di2 R9200 semi-wireless electronic groupset.

While some went even bigger, VDP opted for the new ‘standard’ 54/40 tooth Dura-Ace R9200 crankset.

Given the mostly flat parcours, he likely paired that with the tightest cassette Shimano now offers at the Dura-Ace level – an 11-30t option.

It’s fun to note that today’s ‘tight’ cassette features a larger cog than what was available with the widest ‘climbing’ cassette (an 11-28 tooth) offered with Dura-Ace a decade ago.

Cancellara used 11-speed, mechanical Dura-Ace 9000, with 53/42t chainrings. At the rear, he had an 11-25t cassette paired to a short-cage rear derailleur (upgraded with a Berner oversized pulley wheel system and ceramic bearings).

A Di2 groupset was available to Cancellara, but many at the time considered electronic groupsets too unreliable for the travails of racing over cobbles.

The situation has almost universally shifted (get it?) nowadays, with only Peter Sagan still opting for mechanical shifting at the 2023 edition of the Hell of the North.

While VDP used Shimano’s latest Dura-Ace R9200 dual-sided power meter crankset, paired to a Wahoo bike computer, Cancellara opted to race without one (though he still used an SRM head unit to track basic metrics such as time and speed).

Whether this is because the matching SRM for Dura-Ace 9000 wasn’t unveiled until later in 2013, at that year’s Tour de France, or because Cancellara simply didn’t want to know his numbers, we’re not 100 per cent sure.

Given the older SRM power meter designed for Shimano’s Dura-Ace 7900 groupset was technically compatible with the new 9000 groupset (Dura-Ace chainrings of that era were 10- and 11-speed compatible), we expect it was the latter, however.

Wheels and tyres – tubeless takeover

Wheels and especially tyres have seen significant developments in the past decade.

Both used wheels with deep-section carbon rims, but Cancellara (like everyone else in the peloton at the time), opted for tubular setup, while MVDP and most of this year’s racers used tubeless-ready systems.

Van der Poel’s wheels also featured disc brakes as opposed to Cancellara’s rim brake wheels.

Beyond that, though, the differences between the wheels are fairly subtle.

MVDP’s Shimano Dura-Ace R9200 C50 rims are wider, and better optimised for wider tyres, but the Bontrager Aelous 5 D3 wheels were progressive for their time (featuring a 27.5mm external rim width). Disc brakes aside, it’s fair to say they wouldn’t look too out of place on a modern bike.

As an icon of the sport, Cancellara was able to use non-sponsor correct FMB Paris-Roubaix tubular tyres – one of the most sought-after tyres for the race, until recently.

Though some (such as former cyclo-cross star Lars Boom) occasionally went even wider, Cancellara’s tyres for 2013 were 27mm wide, which was considered very wide by road bike standards, for the time.

In contrast, much of the peloton now races with wider, 28c tyres for many standard road races, let alone cobbled Classics.

While some Team Jumbo-Visma and Team DSM riders opted to use tyre pressure control systems, van der Poel started this year’s race on a bike with 28c Vittoria Corsa Pro tubeless tyres, but finished on one with 30c tyres (according to Vittoria, though some reports suggest 32c) after a mid-race bike change.

We didn’t see the switch happen on camera, but it’s conceivable this was a predetermined tactic designed to optimise his bike setup for each phase of the race.

Given the first cobbled sector (Troisvilles à Inchy – which has a 3 out of 5 stars difficulty rating) doesn’t come until 96.3km into the race, a planned bike change would have allowed him to race with narrower tyres and higher tyre pressures (optimised for the rapid opening hours raced on tarmac roads), before switching to a cobbles-optimised bike at a certain point.

If cleverly timed (perhaps during a natural break, for example), there could theoretically be little penalty for such a tactic.

Of course, it may also just have been that MVDP suffered a puncture or other mechanical issue at some point and the tyre size swap was purely incidental.

In terms of pressure, James Huang’s report from 2013 says Cancellara used 80 PSI / 5.5 BAR and 87 PSI / 6 BAR front and rear.

We weren’t able to find out what pressures VDP used, but riders from UAE Team Emirates were using pressures around 43 to 50 PSI / 3 to 3.5 BAR in 30c or 32c tyres, and we suspect much of the peloton did the same.

Finishing kit – integration reigns supreme

The difference in finishing kit between the two bikes is heavily reflective of how road bikes have changed in recent years.

Cancellara’s Domane paired a 140mm Bontrager Race XXX Lite carbon stem with a distinctly un-aero, 44cm wide Bontrager RL Anatomic alloy handlebar.

All of the cables route externally of both the handlebar and stem, entering the frame via the head tube.

The only bike in today’s WorldTour peloton which has a front-end this simple is the Giant TCR Advanced SL.

In contrast, the Canyon CP0018 Aerocockpit on MVDP’s bike offers fully integrated routing for brake hoses and gear cables (where applicable), and features an adjustable width handlebar to help riders optimise their position.

We’re not sure how long or wide van der Poel’s cockpit was for Roubaix, but we’d bet he’s running a narrower handlebar than Cancellara did, given the aerodynamic benefits of doing so.

Perhaps as a narrower, carbon aero handlebar is stiffer than a wider, aluminium one, van der Poel opted for a double wrap of handlebar tape on his bike, while Cancellara raced with a single layer of Bontrager cork tape.

Saddles have also seen plenty of development in the past decade.

Back in 2013 (a couple of years before Specialized released its S-Works Power saddle and kicked off a trend for short road bike saddles), Cancellara used a traditionally-shaped Bontrager Team Issue saddle.

MVDP, and many other racers these days, opts for a short saddle with a large cut-out – specifically a Selle Italia Flite Boost Kit Carbonio SuperFlow, in van der Poel’s case.

These are designed to reduce soft tissue pressure when riding in aggressive positions.

Apparel – optimise everything

A decade ago, clothing for road racing was fairly standard.

While there were a few outliers (most notably Team Sky), most teams and riders used non-aero helmets, as well as standard cycling jerseys, bib shorts and socks.

Perhaps as the pre-eminent time trial rider of his generation, Cancellara opted for aero overshoes for Paris-Roubaix in 2013. Considering he also wore arm warmers, though, it may have just been cold.

Nowadays, apparel is another key area for optimising performance.

As he normally does, MVDP used a road-racing specific skinsuit (meaning it has pockets for food) made by his team sponsor Kalas.

As well as a tight, wrinkle-free fit, this features various aerodynamic fabrics strategically used in different locations to improve a rider’s efficiency.

On top of this, van der Poel opted for an Abus GameChanger aero road helmet and a set of tall, Zwift-branded aero socks, which we believe are made by a Dutch company called Aero Cycling Gear.

His shoes were sponsor-correct Shimano S-Phyre RC903s.

How much have bikes changed?

While both bikes still have two wheels, two pedals, drop handlebars, etc, it’s fair to say Paris-Roubaix tech (and road bike tech in general) has come a long way in the last 10 years.

Though some might argue that not every innovation has been a step-forward, it is interesting to note there was an average speed difference of nearly 3kph between the 2013 and 2023 editions of the race (44.19kph versus 46.841kph – the latter being a new record average speed).

This is especially notable when you consider that Cancellara’s 2013 race was, at that point, the second fastest edition of all time (it’s now the fifth fastest ever).

Weather and race tactics will have both played their part in this too, of course. But given the 2022 edition was also raced at a record-breaking average speed, it’s hard to ignore that tech appears to be having a significant impact these days.

What will Paris-Roubaix bike tech look like in 2033? We look forward to finding out.