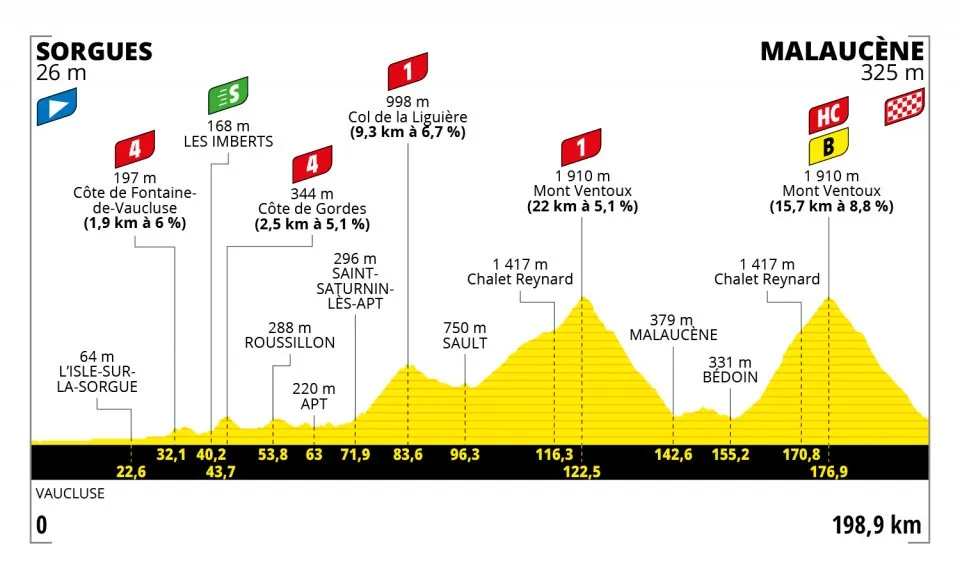

Stage 11 of the 2021 Tour de France is, to put it mildly, a big one. At just under 200km long, the stage takes in two ascents of one of the Tour’s most iconic mountains, the 1,910m Mont Ventoux.

If that wasn’t enough, there are three other categorised climbs during the stage, including a first category ascent of the Col de la Liguière – a 9.3km climb with an average gradient of 6.7 per cent.

All things considered then, there’s a lot of climbing. But what kind of bike is best for a course like this? Traditional wisdom would say a lightweight road bike designed for climbing would be the fastest choice. But, as our understanding of aerodynamics, rolling resistance and performance have developed, the answer is no longer so clear cut.

Although there will undoubtedly be a lot of time spent riding uphill during the stage, there are plenty of flat or rolling roads to consider, plus all of the descending.

Of course, the perfect bike would be one that weighs in at exactly the UCI weight limit of 6.8kg yet compromises nothing in terms of aerodynamics or rolling resistance compared to the best aero road bikes. Unfortunately, that bike doesn’t yet exist (despite what some manufacturers love to tell us).

Could a heavier aero road bike actually save a rider time or energy overall on this stage, even if it comes with a weight penalty? How much difference does bike weight make on fearsome climbs like Mont Ventoux? And is it worth riding heavier, but faster rolling, tubeless or clincher wheels and tyres instead of lighter tubular setups?

To answer these questions, we consulted aerodynamics and performance experts Jean-Paul Ballard of Swiss Side and Dr Xavier Disley of AeroCoach. The answers might surprise you.

Tour de France stage 11 tech analysis | Key findings

- An aerodynamic bike setup is likely to be the fastest option overall for this stage, even with a weight penalty of one kilogram

- Drafting will still play a significant role on the key ascents of Mont Ventoux

- A lightweight bike still holds an edge on the steepest climbs, but a descent to the finish line means a good descender on a heavier aero bike can potentially neutralise this advantage

- Tyre choice is crucial. Clincher and tubeless systems may be faster than tubular setups, even if they’re heavier

- Teams with unavoidable sponsor commitments may not be able to optimise their setups and maximise performance on the day

Stage 11 course analysis

Starting in Sourges, there are 71.9km of rolling roads before the start of the first major climb, the previously mentioned Col de la Liguière.

From the summit of the Col de la Liguière, there are 12.7km of mostly downhill roads leading into Sault, where the peloton will begin its first ascent of Mont Ventoux.

There are three different roads up Mont Ventoux, and this first ascent takes the longest but shallowest (in terms of average gradient) route. At 22.1km long, with an average gradient of 5 per cent, it’s still a monstrous climb by most standards.

There will likely be a relatively large peloton intact at this point, with many domestiques still left to set a high tempo.

The average pace up this climb should, therefore, be relatively high – over 20kph, according to Disley. At least until they reach Chalet Reynard after 18km and enter the moonscape (so-called because the forest disappears and the rocky mountainside begins to resemble the surface of the moon) for the first time.

Following this first ascent, there’s a 20.1km descent into Malaucène. The road is wide and flowing, and will almost certainly be ridden at breakneck speed. "This descent will take around 17 minutes," Disley says. "There are several hairpins you need to brake hard for in the first half, then the rest is much better.”

After this, the race loops around the foot of the mountain to Bédoin, where the peloton will head up the steepest and most feared ascent of Ventoux. Officially 15.6km long at an average gradient of 8.7 per cent, this climb is a brute (and the road actually starts going uphill some 4.5km earlier than the stage profile suggests).

The gradient, particularly in the forest-covered first half, is relentless. Kilometre after kilometre of climbing on 9 per cent-plus gradients. If it’s a sunny day (which it often is in southern France in July), the atmosphere can also become oppressively hot.

It’s on this climb we can expect to see attacks from the main contenders for the GC (General Classification).

With 2020 Tour winner, Tadej Pogačar, currently in the yellow jersey and looking practically invincible, will he and his UAE Emirates team-mates look to attack his rivals again, or defend his lead and save energy for the remaining stages?

Or will any of Pogačar’s remaining rivals work to isolate him on the climb then attack from distance, in the hope they can hold any advantage gained to the finish?

The stage ends with a repeat of the descent into Malaucène, meaning no matter how the favourites go over the summit, there’s still something to play for before the finish line.

Aero vs lightweight bike for Mont Ventoux

So, it’s a hard stage with lots of climbing and descending. That much is obvious, but what’s less obvious is what bike setup is optimal for a day like this.

As already discussed, the best bike is one that arguably doesn’t exist. It’s a bike that hits the UCI’s 6.8kg minimum weight limit exactly, yet is also the most aerodynamically efficient, has the fastest tyres and puts the rider in a comfortable yet miraculously aerodynamic position.

In the real world, though, where sponsorship commitments and equipment limitations exist, riders will have to make compromises. But what should they compromise on – weight or aerodynamics? And what about rolling resistance?

According to Ballard and his team of experts at Swiss Side, the fastest bike setup for this stage is likely to be an aero bike with clincher or tubeless wheels and tyres, even if it weighs a kilogram more.

That might come as a surprise, so let’s dive into why that could be the case.

To answer our question of which bike setup would be faster for this stage, Swiss Side simulated five different race scenarios:

- Time trial: solo rider over the entire course, lightweight versus aero bike.

- Breakaway: effect of two riders working together over the entire course.

- Hill climb: solo rider on the Bédoin ascent of Mont Ventoux, lightweight vs aero bike.

- GC rider and domestique: Team (two riders) on the Bédoin ascent of Mont Ventoux, lightweight versus aero bike

- Descending: solo rider on final descent off the summit of Mont Ventoux, lightweight versus aero bike.

Given the GC riders will almost certainly arrive at the foot of the final ascent of Mont Ventoux in what remains of the peloton, with some mountain domestiques, simulations four and five are arguably the most relevant to the race.

Nevertheless, the other three scenarios offer intriguing reading for breakaway specialists and amateurs taking on similarly mountainous rides.

Swiss Side race simulation

Before we delve into the results, let’s take a look at how the simulations were set up and what variables they account for.

Swiss Side’s performance simulation tool models the time taken to complete a given course, taking into account variables such as the course profile, total system weight (rider plus bike), aerodynamics, rolling resistance, drivetrain friction and rider power output. The simulation tool can also account for environmental factors such as temperature, air pressure and density, and wind.

As expected, the simulated course is stage 11 of the 2021 Tour de France, though in some scenarios, shorter sections of the course (such as the final climb, for example) are simulated to provide greater insight.

Our ‘lightweight bike’ weighs bang on the UCI weight limit of 6.8kg and has a rider plus bike CdA (coefficient of aerodynamic drag multiplied by frontal area – a figure that essentially tells you how aerodynamic something is, with lower numbers being more aerodynamic) of 0.280.

The ‘aero bike’ is assumed to weigh one kilogram more at 7.8kg and gives a rider plus bike CdA of 0.260.

Swiss Side says these weights and CdA numbers are roughly equivalent to bikes like the Cannondale SuperSix versus the SystemSix, the Canyon Ultimate versus the Aeroad, and the Cervelo R5 versus the S5.

CdA is also adjusted when simulating specific situations like an aero tuck on descents or standing up while riding steep climbs.

For each simulation, the rolling resistance coefficient (Crr) is assumed to be constant at 0.0033 for both the lightweight and aero bikes.

Given a lightweight pro bike would typically be running tubular tyres (tubular tyre systems are lighter than most clincher setups) and a heavier aero bike may have clincher or tubeless tyres, this arguably should also be accounted for, though.

With this in mind, Swiss Side also simulated the effects of changing rolling resistance across both the entire course and final climb.

Our virtual test dummy is a typical GC type rider, with a weight of 63kg and a Critical Power (similar to Functional Threshold Power) of 360 watts.

For the team breakaway and domestique scenarios, the reduction of aero drag offered by drafting the leading rider is taken into account by the simulation tool.

In simulation number four (GC rider and domestique), it is assumed the domestique makes it to 3km from the summit of Mont Ventoux, leaving their team leader to go solo from that point.

While it's worth pointing out that any simulation is just that – a simulation that can't account for every scenario or influencing factor on the road – the results offer a fascinating insight into the importance of equipment choices.

So, what's fastest?

Time trial: solo rider over the entire course, lightweight versus aero bike.

For a solo rider on the lightweight climbing bike, the simulated time taken to cover the entire course is 05:23:24, with an average speed of 36.5kph.

The aero bike setup, however, is faster over the entire course by 00:03:16 minutes (-1.0 per cent of total time) with an average speed of 36.9kph.

- Winner: Aero bike

No surprises here. Despite all the climbing, when you’re alone in the wind, the aero bike beats the lightweight bike in what is essentially a time trial.

Breakaway: effect of two riders working together over the entire course

Both riders are considered to be on the aero bike setups. The work is shared between the riders in a power-optimised way in order to be as efficient as possible.

The time saved by two riders working together compared to a solo rider on an aero bike is simulated to be an additional 00:04:46 minutes (-1.5 per cent of total time) with an average speed of 37.5kph.

- Winner: Two riders

Again, no surprises here. Two riders sharing the workload is better than one.

Hill climb: solo rider on the Bédoin ascent of Mont Ventoux, lightweight vs aero bike

For a solo rider on the lightweight climbing bike, the time taken to cover the final climb is simulated to be 00:58:53 minutes with an average speed of 21.5kph.

The aero bike setup is simulated to be slower over the final climb by 00:00:19 seconds (+0.54 per cent of total time) with an average speed of 21.4kph.

- Winner: Lightweight bike

This climb is long and steep enough for weight to matter more than aerodynamics in isolation. It’s a close contest, but 19 seconds is a time gap no Tour contender would want to give up to a rival.

GC rider and domestique: Team (two riders) on the Bédoin ascent of Mont Ventoux, lightweight versus aero bike

For two riders working together in a power optimised way on lightweight climbing bikes, the time taken to cover the final climb is simulated to be 00:57:51 minutes with an average speed of 21.9kph. This is 00:01:02 minutes (1.75 per cent) faster than the solo rider on the lightweight climbing bike.

The same two riders on aero bike setups are simulated to be slower over this final climb by 00:00:22 seconds with an average speed of 21.8kph.

- Winner: Team on lightweight bikes

Aerodynamics and drafting still matter on the climbs, especially when you’re riding at pro speeds. Having a teammate to draft can therefore provide a significant advantage, even on a steep climb, and a lightweight bike provides an additional weight-saving advantage when looking at the climb in isolation.

Descending: solo rider on final descent off the summit of Mont Ventoux, lightweight versus aero bike

On the final descent to Malaucène, a solo rider on the aero bike setup would be 00:00:24 seconds faster compared to the lightweight bike setup.

- Winner: Aero bike

At the high speeds experienced during descents, the only thing slowing you down is aerodynamic drag. It’s no surprise then that the heavier aero bike has an advantage in this scenario.

It’s also notable that the time gained on the descent potentially outweighs what is lost on the preceding climb. Given this stage isn’t a summit finish, this should be taken into consideration.

Rolling resistance simulation: tubular vs clincher/tubeless tyres

Though tubular wheel and tyre systems can be significantly lighter than equivalent clincher or tubeless setups, they are also generally considered to have a measurable disadvantage in terms of rolling resistance.

Because of this, we’ve seen a big shift to clinchers and tubeless setups for time trials in recent years, and many professional teams are now using similar setups for road stages too.

According to Swiss Side, this disadvantage can be as large as 30 per cent, though the exact difference will depend on which two tyres are being compared.

In this worst case scenario, increasing the simulated Crr from 0.0033 to 0.0043 results in the following time increases for a solo rider:

- Entire course: 00:02:45 minutes

- Final climb: 00:00:33 seconds

It’s notable that if the lightweight bike uses tubular wheels and tyres (which is a fair assumption), the potential increase in rolling resistance could cancel out all of the advantage gained from lowering the bike’s weight.

As noted mathematician Robert Chung once said, “weight weenies should be Crr weenies”.

Overall winner: aero bike

“The aero bike is the fastest setup for this course," says Ballard.

“For courses which have a summit finish, a lightweight climbing bike could bring a strategic advantage for the final climb. On this course, however, where the final climb is paired with a descent of equal magnitude, the advantage the lightweight bike holds on the climbs is neutralised.”

However, Ballard points out that this makes the assumption both bikes use wheel and tyre combinations that have the same rolling resistance, which may not be the case.

“If the lightweight bike uses tubular wheels and tyres and the aero bike uses clincher or tubeless tyres, then it is likely any advantage due to lighter weight would be negated due to the increased rolling resistance of the tubular tyres," he adds.

What will the pros actually choose and why?

Whoever wins on the day will, first and foremost, need immense power and tactical acumen, but it’s clear that equipment choices can also play a role in affecting a race outcome. This is especially true at the highest level, where the margins between winning and losing are so small.

For riders whose team sponsors only provide one all-round road bike (like Team Ineos Grenadiers and the Pinarello Dogma F), the frameset choice will be made for them.

There’s still plenty of scope to optimise wheel and tyre choice, though, and we may even see some special-edition bikes with lightweight paint jobs for select riders (as is often noted, paint can add a significant amount of weight to a frameset).

Those who get a choice of frameset – and who happily switch between bikes – will have a bigger decision to make.

However, despite what the simulations say, don’t be surprised if we see most of the overall contenders opt for bike setups that are as light as possible – aerodynamics and rolling resistance be damned.

The 'feel' of the bike and tradition appear to still be of great importance to many professional riders, and the peloton’s fanatical obsession with weight continues unabated.

With that said, while a 10 per cent reduction in aerodynamic drag could save around 27 seconds, according to Disley, a 1-kilogram increase in mass could also incur a 37-second penalty on the final ascent from Bédoin.

Looking at how the actual race is likely to play out on the slopes of Ventoux, Disley also warns getting dropped on either climb, and therefore losing the key drafting benefit of whatever is left of the GC group, could be disastrous.

Unless this happens near the summit, regaining contact with the group on either descents could be an arduous and risky task, even if the time gap would be small in theory.

On the other hand, an extra kilogram in mass plus a more aerodynamic setup could be worth somewhere in the region of 26 seconds on the final descent, according to Disley.

If a rider can make it over the summit at or near the front of the race, strong descenders could then profit from a heavier and faster bike at this point.

Clearly then, there’s a balance to be had. While the simulations appear to definitively show the aero kit is the faster choice, there are significantly more variables at play in the real world, because of the tactics and drafting dynamics of the peloton.

Exactly where the balance lies may be different for each rider and their unique physiological characteristics, so it will be fascinating to see what decisions the teams and their riders make on the day.