A couple of weeks ago, the UCI announced it would be undertaking an “in-depth analysis” on the “current and wider trend in time-trial helmet design, which focuses more on performance than the primary function of a helmet”.

Released the day after the striking Giro Aerohead II debuted at Tirreno Adriatico, the UCI’s statement specifically referenced that helmet, along with several others, and included a note that the ‘headsock’ component of Specialized’s TT5 helmet would be banned from 2 April 2024.

Staggeringly, all the helmets mentioned in the statement received official approval from the UCI prior to their use in the WorldTour.

Any item of prototype equipment must, per the UCI’s technical and equipment regulations, have prior approval before being used in a sanctioned event – and there’s no evidence to suggest any team or brand didn’t follow this protocol.

It’s reasonable to assume the UCI knew exactly what was coming and confirmed all of the helmets adhered to its current rules.

So why, then, did the UCI feel compelled to make a statement saying these helmets raised “a significant issue”?

Because, it seems, it doesn’t like the way they look.

This sad yet predictable about-face is the latest in a long line of interventions from the UCI, which stifle innovation and dent the sport’s commercial viability.

According to a report by Sporza today, the UCI may be about to row back on its concerns surrounding Giro’s Aerohead II. While that may be a win for Giro, this in itself could be damaging – the UCI's proclivity for reactive governance and the uncertainty that creates for the sport remains the real issue.

Patchwork regulations

To look at the infamous Clarification Guide of the UCI Technical Regulation, is to see a patchwork of regulations – often applied in response to a manufacturer, team or rider trying something new.

At the beginning, this document states “The UCI Regulations assert the primacy of man over machine. Observance of the regulations by all parties involved facilitates sporting fairness and safety during competition”.

This is a laudable statement, but what the UCI often seems most concerned with is the way things look.

There was and has been no statement from the UCI about the risks of head-down riding, and/or how its regulations surrounding rider positions on time trial bikes may promote this style of riding, since Stefan Küng’s crash at the 2023 European Time Trial Championships, for example.

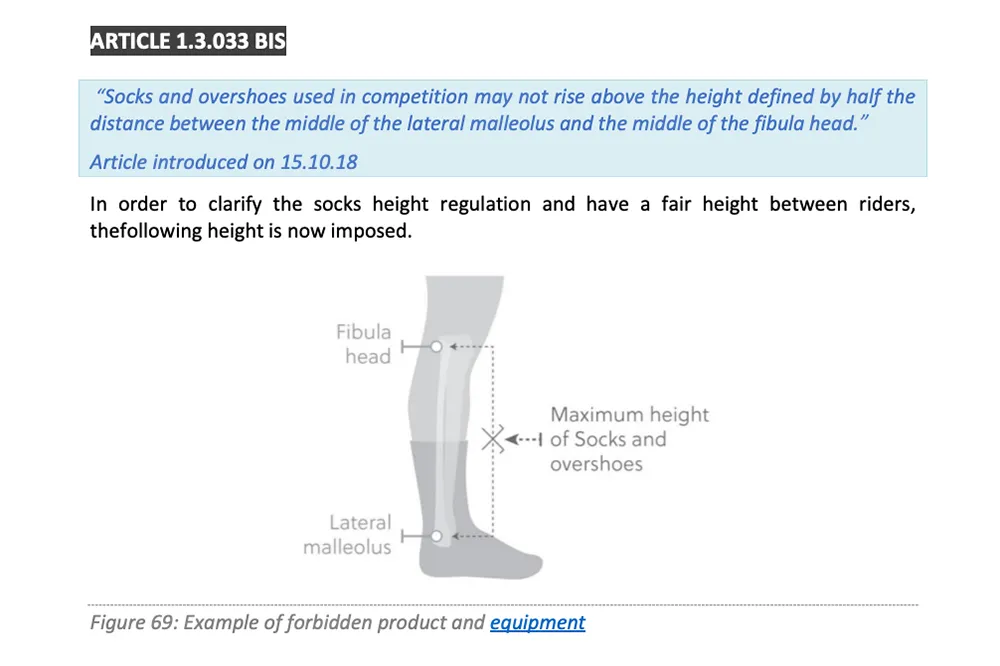

Perhaps it’s working on something behind the scenes, but the difference between the UCI’s lack of response to that crash and its cause, and its very public reactions to the unveiling of Giro’s Aerohead II helmet or to the creeping rise of sock heights, is stark.

Likewise, the argument this upcoming analysis will serve to protect “the primacy of man over machine” doesn’t hold water either.

Giro’s Aerohead II is not vastly different from existing time trial helmets, which the UCI accepted without comment.

The major innovation on Giro’s helmet is that the body extends forward of the rider’s forehead, rather than just backwards.

In what sense is the Aerohead II’s shape or Specialized’s head sock any more “non-essential” than the long tails of ‘traditional’ time trial helmets, such as Kask’s Bambino Pro Evo, Bell’s Javelin or even Giro’s original Aerohead?

The UCI can say the Giro Aerohead II, Specialized TT5 and POC Tempor (which has been around since 2012) are “radical designs”, but all fall within the current regulations.

This is because while there are maximum permitted dimensions for helmets, there are no rules regarding shape.

The rules even state helmets “already manufactured” or “already at the production stage” and “on the market” before 1 January 2023 don’t need to comply with its dimensional rules – meaning there’s one rule for old helmets and another for new ones.

This doesn’t make any sense. If there are good reasons (in terms of safety or sporting fairness) to limit the size of helmets, then any helmets that fall outside of the predetermined limits should be banned in competition.

If there aren’t, then why is the rule in place? It’s a mess.

Let’s not forget, the main point of a bike race is (generally) to find out who’s the fastest from A to B.

Unlike sports such as artistic gymnastics, snowboarding or surfing (to name three), there are no points or prizes for style or ‘difficulty’.

The job of any governing body is to administer fair competition and develop the sport. This, of course, includes the regulation of equipment and technology, and I’m not calling for a regulatory free-for-all in any sense.

Rather than agreeing a set of regulations in collaboration with key stakeholders, though, the UCI simply appears to react to the churn of new developments, without a clear or consistent strategy.

Reality check: maybe cycling isn’t as cool as many think

I know what many are thinking: 'But these new helmets do look ridiculous – they’re ruining our beautiful sport!'

The first part may be true. However, too many people have an inflated opinion of how ‘cool’ cycling is.

I’m no arbiter of style, but let’s face it; Lycra skinsuits, cycling shoes with cleats, pointy helmets and bikes with funky handlebars have never been cool or good-looking.

Brands such as Rapha do a good job of convincing us otherwise, with carefully curated marketing and ‘storytelling’. But when we awkwardly clip-clop into a cafe for a post-ride coffee, the other patrons typically aren’t looking over in admiration.

If we want to know what the general public thinks of cycling and bike racing, the 2017 mockumentary film, Tour de Pharmacy, is probably a good barometer.

Likewise, the in-cycling comparison of modern time trial helmets to Spaceballs (a 1987 parody of Star Wars) was funny the first time that joke was made, but it’s boring now we’ve all seen it a hundred times.

Can’t we just accept the days of professional bike riders looking like Fausto Coppi are behind us? Fans of Formula 1 don’t complain cars from the modern era don’t look the same as those from Juan Manuel Fangio’s (1950s) era, after all.

Of course, events such as L’Eroica and the Goodwood Revival exist to serve fans of bygone eras, but few would argue the equipment used in these events is what the modern professional equivalents should look to emulate.

It’s also worth remembering the vast majority of cyclists are not sponsored professionals and are free to ride or wear whatever they want.

If you think the Giro Aerohead II or anything else looks dorky, that’s absolutely fine – no one will force you to buy or wear it.

Calling for things to be banned simply because they look different is no way to manage a professional sport.

Poor regulation damages the sport and benefits the wealthy

Opinions on aesthetics aside, this reactive approach to regulation actively harms the sport.

Giro, Specialized and any other brands falling foul of the UCI’s latest intervention will have invested lots of resources into making these helmets.

How can any brand be expected to develop equipment for use in UCI-sanctioned events, or sponsor any professional team, if the UCI can’t be trusted to keep regulations stable for a reasonable period, instead choosing to ban things it doesn’t like the look of on the hoof?

Echoing this sentiment in a post on Instagram, Giro aimed thinly veiled criticism at the UCI, saying: “We design for sport. Sport has rules. We play by the rules”.

Aside from the fact this is unfair (which goes against one of the stated principles of the UCI’s own rules), these kinds of bans also tend to benefit the richest teams, brands and athletes, because everyone is forced back to the drawing board to come up with a new performance advantage.

In a sport with no spending cap, those with the greatest resources are primed to simply spend their way out of any problems.

For example, when the UCI banned Team Sky’s Castelli Body Paint 4.0 speed suit (which purportedly had ‘vortex generating pimples’ on its sleeves), Castelli and Team Sky developed a new system involving a paper-thin skinsuit and an aero baselayer for the next season.

In contrast, teams and brands with fewer resources aren’t as able to keep up with an ever-changing regulatory landscape, meaning any technological disadvantages tend to remain in place.

How should the UCI conduct its regulations?

As I mentioned early on in this article, I’m not calling for a regulatory free-for-all.

There are solid grounds for regulating the size and shape of helmets worn in UCI-sanctioned events.

My issue is with what I see as the arbitrary manner in which the UCI governs the use of technology within cycling.

More often than not, it seems to me to be more concerned with protecting its own idea of the sport’s image than promoting fair and safe competition.

If the current technical regulations allow brands and teams too much leeway in finding performance advantages in certain areas, the fault lies with the UCI – it wrote the rulebook, after all.

Blaming the brands and design teams for simply doing their jobs is ill-considered. Especially as there appears to be no evidence showing any of these “radical designs” prioritise performance over safety, as the UCI’s statement suggests.

As with motorsports, the UCI may be best advised to treat professional cycling more like a formula (such as Formula 1, Formula 2 and so on) governed by a set of detailed technical regulations that remain largely static until a predefined point.

In principle, all brands and stakeholders would then be well-prepared for any regulatory changes, enhancing development and fostering healthy competition – and avoiding the kind of reactive and damaging backpedalling we see all too often.