"I’m known as the mad cyclist, aren’t I,” says Graeme Obree. It’s said with a smile in his voice but, sitting at the other end of a phone line, it’s difficult to tell how this comment really makes Obree feel.

I reassure him that to cycling fans, the former world hour record holder, world champion and cycling innovator is simply a hero, an inspiration. It’s an over-used cliché, especially in sport, but Obree can surely lay claim to the honour of being labelled a legend.

Obree has a point, though. Ever since his brilliant, and searingly honest, autobiography The Flying Scotsman revealed some darker truths, some do simply see him as the ‘mad cyclist’.

Talking from his home in Ayrshire, perhaps Obree is worried that this sobriquet will rear its head again as he outlines his plans for autumn 2009. At 43 he is remembering what he once had. He is looking at the world hour record that he broke twice in the 1990s. And he is thinking, seriously thinking, about one last throw of the dice.

Flashback 20 years and cyclists didn’t appear in television adverts for cereal. They didn’t appear nude on the front covers of Sunday supplements. They didn’t even get on [TV quiz show] A Question of Sport. Most members of the British public thought cycling was odd, weird, something only the French did, even though we had an Olympic champion in Chris Boardman.

Hard to believe now with Chris Hoy, Victoria Pendleton and Mark Cavendish mainstream superstars. Harder to believe still is that Graeme Obree didn’t become a mainstream superstar on 17 July 1993. This was when, on a bike known as Old Faithful that he’d designed and built himself and only the day after a failed attempt, the man from Ayrshire rode 51.596km in an hour on the velodrome at Hamar in Norway: a new world record.

Boardman went further six days later, but Obree reclaimed the record in April 1994. In ’93 he also won the World Individual Pursuit Championship, a feat he repeated in 1995. And he was repeatedly contesting cycling’s governing body the UCI as it banned his bike and his revolutionary tuck and ‘Superman’ riding positions.

The whole truth

Surely this was PR gold – success, controversy, plucky British brilliance and innovation versus petty European officialdom. Graeme Obree should have been massive. But there was a problem: Obree was different. Not just in his methods and his bikes but in his personality too – the mad cyclist.

During his riding career, Obree battled depression, crushing self doubt, alcohol binges and attempted suicide on at least two occasions. In 2003 he published The Flying Scotsman and recounted not only his success but his problems too. Not your usual anodyne sports biog full of great moments and anecdotes about dressing room practical jokes.

“I was being honest,” says Obree. “I started writing the book as a matter of therapy more than anything. It was kind of cathartic. When I started I wasn’t sure I was even going to publish the book, but I knew that I wasn’t just going to write an ego trip or chronological diary. I wanted to do the right thing.”

He did the right thing and did publish but, he says, as soon as the book hit the shelves he wished he hadn’t. “When the first reviews came out I thought, ‘Oh no, what have I done?’ One of the first said that I was an alcoholic bum and it was awful. I’d made a huge mistake. But then I started getting letters from the public, and just one of those justified the effort. Most were from people who’d been touched by mental illness, themselves or in their family, who’d not been able to get to grips with it, but were saying the book had helped them.”

A Hollywood film of the book followed in 2006, but it didn’t bring Obree anything more than angst. “Again I saw the reviews and I thought, you’re joking! It was all about the mad cyclist again. I thought I don’t need this and just kind of hid away. I guess you could say I’ve had a gap decade.”

Three years on from the film and after more tough times – the death of friend and fellow champion rider Jason MacIntyre (killed while training on his bike) and divorce from his wife Anne – Obree says that he no longer wants to hide.

It’s a decision born from both personal drive and a feeling that he should be giving something back. “I’m not saying that I will break the hour record, but I am aspiring to do it. You know, last year was the first year since I was 16 that I didn’t win a bike race.”

Comeback kid

Certainly, Obree’s plan can’t be instantly dismissed as the pipe dream of a once great athlete reluctant to admit it’s over. Or of someone chasing one last pay day – he was part of the winning team in the Scottish 10-mile TT championships as recently as 2006. He says two years ago he was still riding sub-20 minute 10s in local events.

The comeback wouldn’t be unprecedented either. After Boardman broke Obree’s first hour record in 1993, 42-year-old Italian Francesco Moser – whose record Obree had smashed – rode further than Obree, if not the Olympic champion.

“I don’t think that you’re physically hampered from winning at the highest level just because of age,” he says, referencing Moser and riders like 50-year-old Frenchwoman Jeannie Longo who finished fourth in the 2008 Olympic Road Race. “To diminish yourself just in terms of age isn’t justified. I don’t think you can use it as an excuse, not if you’ve kept it going.”

Obree’s confidence is further boosted by recalling the build-up to his first record. “I’ve had a good winter of riding,” he says. “That’s something that I couldn’t say in 1993. I came into that season having done almost nothing, but I managed to get out on the roads on my mountain bike the winter just gone.”

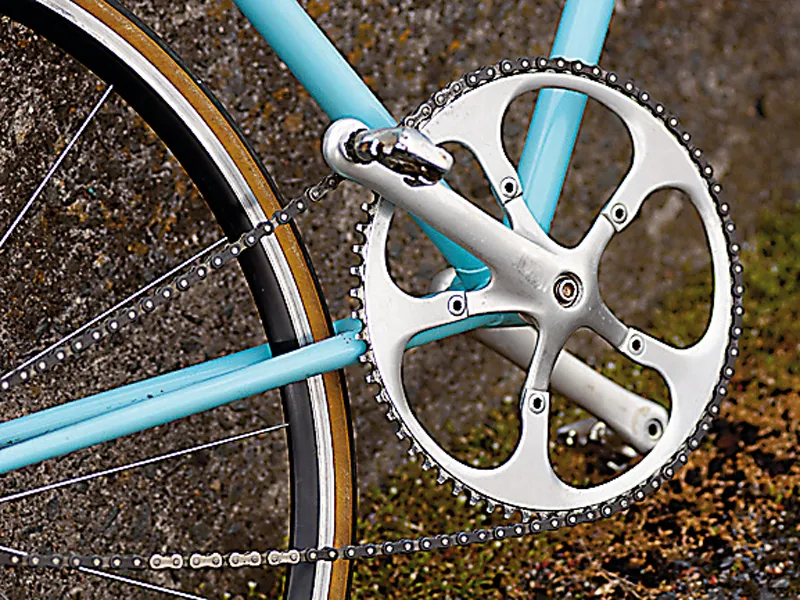

Followers of Obree won’t be surprised to hear that his mountain bike is made up of old tubing, components and even jump forks from a bike shop scrap pile. He built his first hour record bike, Old Faithful, in his own workshop. Nearly 20 years on, Obree is planning to take another self-build onto the track.

Unlike with Old Faithful, though, which with its narrow bottom bracket, non-existent top-tube and odd handlebars led to a UCI ban and the introduction of a raft of strict regulations, Obree is confident that his latest, yet unnamed, steed is fully legal.

“I’ve built it within the limiting factors of the regulations,” he explains. “It’s deliberately long so my arms are stretched onto the drops for the best aero position. It’s also longer at the rear as this puts weight towards the front of the bike. On a standard twitchy track bike, you can be all over the track in the last 20 minutes of an Hour attempt – you start to lose consciousness and motor control.”

Obree is sure that UCI scrutineers won’t have cause for quarrel. Built from Reynolds 653 tubing and silver soldered, this new bike, he says, certainly weighs more than the 6.8 kilo limit.

Old-school training

Over the next few months Obree plans to train hard on this bike, working both on the turbo trainer and the road. Unlike most modern pros and his contemporary Boardman, he takes a refreshingly low tech approach. No power meters, not even a computer when on the road. “I find them a distraction,” he says.

Most of his riding will consist of two to two-and-a-half hour efforts on the road. “I’ll go out on warm, still evenings when there’s less traffic. And I don’t want a headwind as I’m riding a 67/13, a 138in fixed!”

On the turbo, he’ll simply ride hard 40-minute sessions, trying to ride faster and further each time. In fact, he’ll be doing it pretty much how he did it in the early 1990s – no sports scientists, psychologists, coaches or super-quick training partners. No British Cycling (BC) help, either.

“I think the current BC setup would have helped me in one way for sure,” admits Obree. “I wouldn’t have had to worry about money in between seasons, trying to find sponsorship. That used to do me in.” However, he isn’t convinced that the more structured, results-based approach – or conveyor belt as he calls it – that BC uses so brilliantly now would suit someone as non-conformist as him.

“If snooker was run like cycling is today, then there’d be no Ronnie O’Sullivan, would there? You never know which Ronnie is going to turn up, and I was like that. I could be brilliant or terrible. There was no in between with me.”

As an example, he cites his triumph at the 1995 World Track Championships. “It would not have happened under today’s system,” he insists. “I tried out the Superman position [with his arms stretched out in front of him on aero bars] for the first time at the Good Friday meeting at Herne Hill. It’s a long track and I was lapped by Rob Hayles.

"I don’t think I’d have got a second glance today, but Doug Daley [GB coach] still asked me if I wanted to ride the World Cup in Athens. He put his faith in me and because he stuck his neck out I trained bloody hard and made sure I won.”

Despite feeling he wouldn’t fit easily with new BC, Obree is delighted that riders like fellow Scot Chris Hoy do. “I was totally into the Olympics,” he says. “It was just wow, this is so good for cycling. For so long it was seen as second rate, a Cinderella sport. Who’d have thought 10 years ago that when talk is of British sporting success they’d show clips of cyclists? In the Nineties it was just drugs, how we never win. Jeez, it’s never been this good.”

But can Obree ever be ‘this good’ again? And why is he even contemplating a return? For someone so seemingly fragile surely it can’t be a good idea? He has always had a love/hate relationship with the sport. “One day I’d be happy riding, then the next I’d be feeling that I hated it, that there was too much pressure. Then I’d never want to get on a bike again.

“There’s a higher incidence of depression among elite sport people than the general population,” he says. “We have a weird level of contentment. Think about it – if you have to win every race then there’s something not right about you. It’s not a healthy obsession, not the sign of a balanced, self-fulfilled person, happy in their own skin. If you race and can just be happy to do your best, then you’re well rounded.”

Then, rather tellingly, he continues: “I don’t have any choice – once I started thinking that I could get onto that pace and have a good day then I had to do it.”

In search of happiness

Obree says he’s happier than he has been for a long while. “I reckon I’ve lost about a kilometre just because of that. I’ll have to make up the rest by training and good eating.” He’s not putting himself quite into the ‘well rounded’ category yet, though. “I’ve still got this drive to find out what I can do. It’s probably the last chance saloon, but I don’t want to get to 50 and think, my goodness, I should have gone for that record.”

Obree says that he feels a pang of guilt that he hasn’t so far put as much back into cycling as he’d like to. The plan was to get involved when the film was released, but it just didn’t happen.

After the Olympic success, figures including Hoy and Boardman made noises about Obree joining the BC setup. “I would love to do something to encourage young people to get into any sport rather than drinking or smoking or getting into trouble on the street.”

To this end he has agreed to a couple of charity rides in the summer, and surely an ambassadorial role for a man like Obree would be perfect? He’s a shining example of how sport can help you battle the darker side of life.

But what if the Hour record turns out to be a folly? What if it is closer to the bloated boxer collecting a last purse than the phoenix-like rise that Obree, and his fans, will want?

“It still wouldn’t be the most embarrassing thing I’ve done in my life,” he says. “Some friends have asked if I’m panicking, but I said to them having written up my book then I can’t do anything more embarrassing can I? I’m already known as the mad cyclist, after all."