Every cyclist’s bucket list and every cycling guide worth its salt lists Mont Ventoux – the Giant of Provence – either at the top, or very close to the top, of the world’s most feared and revered climbs.

The huge peak rises up out of the plains of Provence, from the olive groves and vineyards, like a whale breaking the surface of the ocean.

The Ventoux summit, used as a reference point by pilots flying down to the French Riviera, nudges 2,000m and, on first sight, always puts the fear of God into most cyclists.

Unlike the majority of the most notorious mountain climbs, the road to the Ventoux summit is not a pass strung between peaks. The long climb, both from the north side and the more famous south side, snakes its way upwards until finally, dramatically, it reaches the very peak, the highest point on the humpback ridge.

Mythology of the Mont

From the summit, you can look south towards the Luberon hills and beyond towards Aix-en-Provence, the Bay of Marseilles and the Mediterranean.

To the east, is the wild Mercantour national park and the Italian border, while visible to the north are the French Alps and the Mont Blanc massif.

Few climbs in cycling have been so mythologised. Among road cyclists, Ventoux is now perhaps the single most visited mountain in Europe.

Everyone from Alastair Campbell, Tony Blair’s director of communications in Downing Street, to Alain Prost, former Formula 1 world champion, has ridden a bike up it and posted selfies of themselves, their bike and those jaw-dropping 360-degree views from the sky-scraping summit.

But it is not a summit to linger on. The great French sportswriter, Philippe Brunel, captured the mountain best when he wrote “the Ventoux is a riddle, an elusive summit, whose obsessive power and whiff of tragedy addle the mind.”

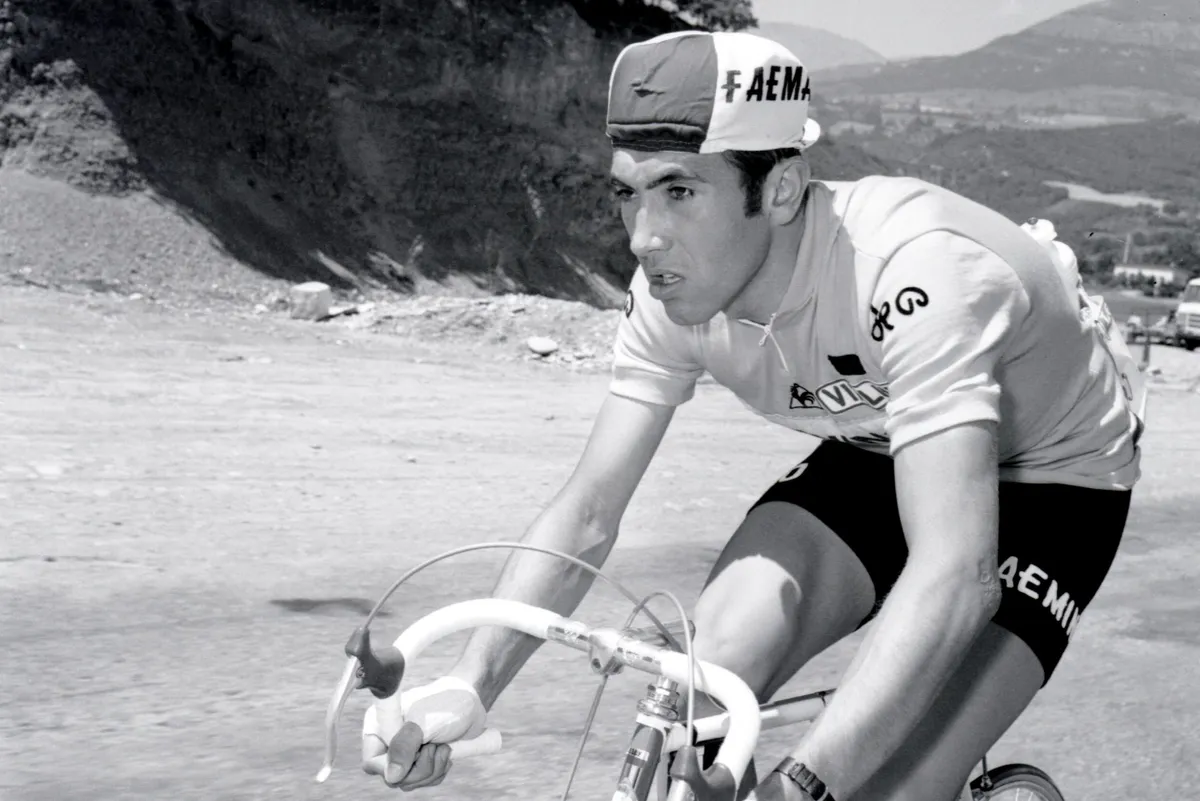

Eddy Merckx, winner on the Ventoux in the 1970 Tour de France, said about the atmosphere in the professional peloton as a major race nears the foot of the climb: “They’re all scared. Everybody’s afraid.”

About his days racing on the Ventoux, the Belgian legend said: “It gets so quiet you can hear a fly buzzing through the peloton.”

While Eros Poli, the Italian rouleur who found himself in a solo break, climbing Ventoux in heatwave conditions in the 1994 Tour de France recalled after he’d retired from racing: “I thought I was dying” and “I’d never ridden so slowly before.”

But the Ventoux is legendary, not just for the brutality of its three ascents or the drama of its summit, but for other reasons too. In France, it is also known as the killer mountain.

Most famously, in 1967, during that July’s Tour, Tom Simpson collapsed and died. Simpson was a much-loved world road race champion, a BBC Sports Personality of the Year winner, a homebred hero. Yet he died high on the barren slopes of the Ventoux, far from home, at the very limit of his suffering.

His death was a terrible tragedy, one of the Tour’s darkest hours, and blamed widely on his use of amphetamines, although the story is more complicated than that.

The day after Simpson died, there was an obituary in the Yorkshire Post. “I know the place well where Tom died,” his teammate Brian Robinson said. “It is a hill of death.” Yet Simpson’s not alone in having met his maker on the desolate flanks of The Giant.

Hikers, cyclists, motorcyclists, quad bikers, walkers and skiers – it is a treacherous place where extreme storms and dramatic high-altitude weather fronts can suddenly turn the summit into a death zone.

“Every year, there’s a few people who die on the Ventoux,” former professional racer and Vuelta a España winner, Eric Caritoux, tells me. The Frenchman grew up in the shadow of the mountain and now works in the vineyards on its southern slopes.

Jekyll and Hyde

Riding around the foot of the Ventoux, through the bucolic honey-stone villages and vineyards, past the sleepy cafes and wine co-operatives, it’s hard to imagine that the mountain that dominates the region could be so dangerous. Yet since it was first included in the Tour de France in 1951, there has always been drama.

That afternoon, post-war crowds flocked to the roadside to see riders such as Fausto Coppi and Louison Bobet race up the mountain’s north side, the ascent from Malaucène.

There was something magical, liberating even, for the French, in seeing the peloton climb the devilish Ventoux, in a stifling heat haze, so soon after the German occupation, which had been bitterly resisted in Provence.

But the fear and infamy of the Ventoux took hold in 1955 when the temperatures were so intense that the tarmac was melting on the approach to the climb. Swiss maverick Ferdi Kübler was determined to show the Ventoux who was boss. As he attacked the climb, rival professional, Raphaël Géminiani, warned Kübler: “The Ventoux is not like any other climb…” Kübler is said to have shouted back: “Well, Ferdi’s not like any other rider…”

The stories of that day have passed into cycling folklore. Kübler is said to have been frothing at the mouth by the time he reached the summit of Ventoux, and to have tumbled into a ditch, set off in the wrong direction and downed beers in a bar, before finally arriving at the finish.

“Ferdi has killed himself on the Ventoux,” he announced deliriously to reporters that evening. Behind him, a darker scenario was unfolding after Frenchman Jean Malléjac collapsed unconscious on the forested climb to the top from Bédoin. He was revived by race doctor Pierre Dumas and given oxygen in an ambulance.

With awful prescience, it was Malléjac who, in an interview 12 years later, foresaw Simpson’s terrible demise. Talking of his own experiences, Malléjac said: “It’s possible I was doped. I don’t want to accuse anyone, but I’d like to know what was in my bidon.”

Just 48 hours after that interview was recorded, Simpson was dead, after collapsing a few kilometres further up the mountain from where Malléjac had lain prone, 12 years earlier. Simpson’s passing accelerated the anxieties over doping and increased the pressures for greater testing of professional riders.

A bitter battle

Perhaps the most famous duel of all on the Ventoux, that of Lance Armstrong and Marco Pantani in the 2000 Tour de France, was also one of the most performance-enhanced.

Armstrong, of course, subsequently admitted to doping in all of his seven Tour wins, while Pantani was found dead in an Italian hotel room in 2004 after a stellar career disintegrated amid a slew of scandals.

Despite all the doping, Armstrong never won a professional race on the Ventoux, a statistic that reveals just how brutal a climb it can be. “If you asked, ‘Give me the top three regrets of your career,’ then not winning on the Ventoux would be one of them,” he said. “It was the hardest mountain,” he added. “I mean, they’re all hard. The Ventoux didn’t require doping any more than any other climb.”

If there are tragic and unsavoury stories associated with the Ventoux, there are also many famous successes.

In 2006, Nicole Cooke became the first British rider to win the five-stage Grande Boucle (the women’s Tour de France), founding her victory on a lone breakaway on the mountain’s north side, from Malaucène, and a breakneck descent to the finish in Isle-sur-La-Sorgue.

In furnace conditions, it was one of the most spectacular lone raids ever seen in cycling. “These are the magic days,” she said later, “the days that define your career, and that you dream of when you’re training in the winter and it’s cold and wet.”

But Cooke will never forgive the British media for the lack of coverage her extraordinary success received, especially given that most column inches at the time were devoted to doping scandals.

“My moment in the sun was taken forever by people who thought so little of my efforts because they were so wrapped up in writing eulogies for the corrupt,” she once told me.

Now, 15 years later, her achievements would make headline news and ensure lifelong acclaim. There’s no doubt that Cooke deserved far greater recognition, not just for her remarkable moment in the sun, high on the Ventoux, but for all her other successes.

By 2013, almost half a century after Simpson’s tragic death and 12 months after Bradley Wiggins’ win, British success in the Tour was almost expected. Chris Froome climbed to a remarkable – and subsequently hotly debated – stage win on the Ventoux as he claimed his first Tour de France, and also learned what a hothouse the French race could be.

Three years later, the Tour was back, but this time the weather dominated events. Due to dangerously high winds at the summit, the finish line was moved down the climb to the shelter of Chalet Reynard, six kilometres below the summit. This meant that all the thousands of fans who would have lined the final kilometres descended towards the new finish area, which was already crowded with TV lorries, team buses and other vehicles.

It was chaos, and as Froome and his group came into the final moments of the stage, they were hemmed in by huge and over-excited crowds, causing a motorbike to crash and fuelling a pile-up of riders in its wake.

It’s hard for the Tour to shock viewers, after all the dramas over the years, but the sight of Froome, clad in the yellow jersey, jogging up Mont Ventoux, was unforgettable. After casting aside his mashed bike, Froome had waited for a replacement from his team car, but the car itself was delayed by the pile-up. So what did Froome do? Like a Forrest Gump in cycling shoes, he ran.

This year, the Tour will be back with a set-piece stage, on 7 July, that includes two ascents of The Giant. The first ascent from Sault is the easiest, but the second, from Bédoin to the summit, will be the most damaging.

Lost in his prime

Tom Simpson’s daughter, Joanne, who now lives near Ghent, is likely to be there on Ventoux, paying her respects and maintaining the memorial to her father, set close to the road, just below the summit. Joanne is a strong person, but then she’s needed to be, to survive the loss of her father at only four years old. She’s also a guardian of his memory and of his reputation, which she feels is too often dismissed.

“Half the people who stop at the memorial don’t even know that my dad ever won another race,” she said. “I sit on the steps and I hear what they say. Nobody knows who I am, but they come up and say, ‘Oh, this is where the doper died.’”

There will be drama on the Ventoux again this summer because there almost always is and a sense of a return to normal. But many of those who know the wild and brutal climb well will be hoping that the scented mountain air will this time be free of Brunel’s ‘whiff of tragedy.’

Top 10 moments

History on Mont Ventoux: The big moments we still talk about today

- 1951: The year of the Tour’s first visit to Ventoux. The stage finished in Avignon, not the summit, and was won by Louison Bobet.

- 1955: Bobet won another stage that crossed Ventoux, but it’s Jean Malléjac’s collapse on the way up that’s remembered.

- 1967: How people think of Mont Ventoux is indelibly linked to the tragic death of British star Tom Simpson on stage 13 in 1967.

- 1970: Eddy Merckx took his only victory on Ventoux at the Tour de France on his way to the second of five yellow jerseys.

- 1994: At 6ft 4in and 85kg, Eros Poli was one of the bigger riders in Tour history, which made his 1994 ride all the more remarkable.

- 2000: Marco Pantani’s victory on Ventoux was soured by big rival Lance Armstrong gifting him the win.

- 2002: French favourite Richard Virenque made the polka dot jersey his own in this period and won on Ventoux in 2002.

- 2009: Spanish flyweight Juan Manuel Gárate scored his only Tour de France stage win in the final mountain stage of 2009.

- 2013: Chris Froome has had mixed fortunes on Ventoux. In 2013 he produced one of his great rides by soloing his way to the summit...

- 2016: ...but three years later he was running up the mountain because a pile-up into the back of a motorbike wrecked his bike.