There's no stopping the technological advancement of the bicycle. Yet no one seems to have reminded Rivendell Bicycle Works founder and president Grant Petersen of this fact, and apparently that suits him just fine. Petersen clings to his beliefs like a mother to her infant child. Like Rapha, Petersen believes strongly in what the cycling days of old conjure up, not only in the mind, but in the simplicity and beauty of a curved, cast lug. His passion goes beyond the aesthetic, though. At Rivendell, there's a focus on practicality beyond anything in our ragtag industry, and this has been enough to keep the company afloat since 1994, the year Petersen started it in the back office of his home in Walnut Creek, California.

As the product and marketing manager for now-defunct Bridgestone Cycles USA, Petersen and crew took on the big boys by providing a range of bikes that, as he said when news broke of the closing of the US division in early 1994, "we and our friends would ride. You can't go to war with the giants of the industry and use the same weapons." In the same issue of VeloNews, where Petersen was quoted, an editorial was written that summed up the impact Bridgestone had on the industry and consumers alike:

"Bridgestone stubbornly swam against the current, following its better judgment, its more human, more seasoned-bikie judgment. It never tried to sell you that first giddy week with your new "super-bike." They offered bikes you would live with for years, bikes that'd work and work with you, making you perhaps a better, happier, more adventurous bike rider." Petersen developed Rivendell Bicycle Works to be a continuation of that vibe, without the pressures of answering to a rather large parent company.

I had the privilege of working with Petersen when Rivendell was 12 months old, and I was one of three employees. My job was production coordinator at the former Schwinn Paramount factory in Waterford, Wisconsin, run by former Schwinn execs Richard Schwinn and his business partner Marc Muller, who called their fledgling company Waterford Precision Cycles. I learned plenty about lugged steel frame and fork production during my two years, and Petersen's steadfast focus on providing a sound product is alive and well nearly 12 years later.

Rivendell Bicycle Works, likes its founder and spiritual leader, is focused on one thing: making the bicycling experience both organic and memorable. Trouble is, the company's ways are unconventional in comparison to our Silicon Valley-esque industry of fashion and progressive innovation. Co-moulded or monocoque carbon frames? Nope, lugged steel, bub. Lycra technical wear? Merino wool, brother. Razor-thin carbon and foam saddles? Leather and copper, my friend. Bikes for time trialing, criteriums or circuit racing? Brevets, cross-country touring or camping is more the pace, mister.

This makes entering the world of Rivendell Bicycle Works either an unforgettable journey or an exercise in futility, depending on whose opinion you seek.

We sought Grant Petersen's opinion on this and other matter, because this is his company, and, well, he always stirs the pot and makes for a memorable interview. His reputation for approaching things differently rose from his 10 years as product and marketing manager for Bridgestone USA, and his unconventional ways, much like Patagonia's Yvon Chouinard, have made him something of a celebrity with Rivendell, which makes him uncomfortable but brings a steady mix of customers to the fold.

BikeRadar: Rivendell is in its 13th year. Is everything with the company where you thought or hoped it would be at this point back in 1994?

Petersen: I know what this answer will sound like: a veiled pat-on-my-own back for having lasted, but I can't help how it sounds. The answer is: If I'd known what the work would entail and how hard it would be, I'd have known it would never work, no doubt about it. Now, that sounds like I'm saying I've done something really hard for 13 years, and the logical next thought is that I must be smart or good at business or something like that.And, if I say I'm neither, it sounds like I'm bragging about my humbleness, If you want people to say you're good, you go around claiming you're bad, and that kind of thing. But somewhere in there is a simple question, and there ought to be simple answer, and going back to the "where you thought or hoped it would be?" part, I'd have to say I was naïve then and it's where I'd hoped it would be, but I had no right to hope that, given how little I knew about what was ahead.

BR: I recall reading complimentary letters from two Big Bike Companies, sent to you after Bridgestone USA closed in the fall of 1994. Bridgestone certainly carved a deep niche in the marketplace; do you miss those freewheeling days?

They weren't as freewheeling as they may have seemed from the outside. They were fun in the sense that I had a good relationship with the parent company in Japan, and they trusted me and liked me, and pretty much supported things I thought were a good idea. Most of the Bridgestone USA presidents (always Japanese guys) were great, too. The only bad guy was the one who hired me and gave me lots of responsibility and a long leash and let me learn without the harsh consequences for major foul-ups, and for that I'm grateful. He was mean though. Anyway, the good parts were designing bikes, visiting the parts makers and Bridgestone's own factory and learning how things were made. Seeing bins of SunTour Superbe left crank arms in the Dia-Compe factory, seeing pedal bearings packed with fish oil in the SR factory, and seeing hooks hung with Kleins, Cannondales, and Alans, all cut apart to investigate the joinery at Bridgestone, and watching how Nitto tests handlebars.

It was dreamy and perfect for me, as it would be for anybody who liked bikes and was curious about them, and who liked being treated nicely. That describes almost everybody I know, come to think of it.

Over the years as Bridgestone USA grew and my influence grew within it, it got to the point where I was too quirky for the company that many of the sales reps and some of the staff thought we ought to become. The Xo-1 and Moustache Handlebars, and wool jerseys with tagua nut buttons, and the recycled paper catalogues on bland paper sort of bothered some of the slicksters, and I didn't lash out in defence, because I can't do that. So I just sort of internalized it like a sea anemone being poked, and at that point there was the public me and the private me, and I don't miss that part.

BR: You're a consistent person. There were several things you wrote about wanting to do in the 1993 and 1994 Bridgestone catalogues and Bridgestone Owner's Bunch (BOB) gazettes that have come to fruition through Rivendell. Will there be more in the next year or two?

I hope so. There are some things I want to do, and one thing in particular that I want to do that will be terribly misunderstood by just about everybody with an internet connection and a smattering of bike knowledge and historical perspective. Compared to anything Rivendell has "done" in the past, it's way, way out there and sounds, or might sound, inconsistent and off the deep end.

But most of the things I want to do, I think I will do, because they're not that hard. I can't discover new isotopes or play the piano, or even program a heart-rate monitor, but I CAN design bikes and arrange for somebody to make them to our specifications. It is low-level human accomplishments like that that I can do, and so I try to do those things, if that makes sense.

BR: Your main stomping grounds have been Mount Diablo near your home and office in Walnut Creek, CA your entire life. Aren't there other places you'd like to be?

It's a good area, and even though I haven't travelled much, I would BET that the riding here is as good as it is anywhere in the world. When I'm riding in the hills here in March when it's all green, and for a minute I pretend I'm in Scotland -- a place I'd really like to go to when it's not bug season -- then I think "this is as good as it can be." Then I go back to it not actually being Scotland, and I just feel lucky.

I wouldn't mind the ocean being closer, though. Point Reyes, which is about 40 miles from here, might be the only place I'd sort of rather be, sometimes. But the last time I was there I saw too many people wearing brand-new, old-looking leather cowboy hats, and that took it down a notch.

BR: What are the biggest challenges and the greatest joys at Rivendell Bicycle Works?

The biggest challenges are bicycle production and delivery and planning, and how that affects cash flow and customer satisfaction and internal stress and frustration. It's a never ending cycling of sticking our necks way out there with high minimum frame orders that take five to six months to get -- so we have to order bikes before we need them, and that' hard. And then having to pay for them in ten days, just whopping bills of $40K to $100K, or else we pay tons in interest.

In the Bridgestone days it was different, because we had lots of dealers who'd commit to the frames, and a parent company who'd give us six months to pay for them.

The joys are seeing the frames (and bags, and wool) go from an idea to a real thing that people like. Our big mission is getting people comfortable on bikes and in a frame of mind that's comfortable, happy, and not even defensive about not racing.

BR: You have a propensity to stick to your principles in everything you do. Where does that come from?

It's not an internal strength or drive or anything like that, and as far as sticking to principles goes, it's easier to do the things you like and believe in than the other option. The other option isn't a real option, in other words.

BR: Do you remember your first bicycle? How about your first bicycle race? Spoken with Norm Alvis lately?

My first bicycle was a blue, metal-saddled, solid-rubber tired fixed gear bike that would be illegal these days, since it had two wheels and there was no way to stop it. I'm surprised whoever made it made it, but they did. Bushes were the brakes.

My first race was a 19-miler, a Category 4 early season race, and I won it -- and then thought "this racing is going to be easy!" I won a few other races in the next 6 years (from ages 22 to 28 or so), but I never enjoyed it, and even after quitting racing, it took years to get it out of my system. By that I mean, I'd still ride as though I were training, and dressed like a racer -- although a slovenly one. Mentally, I just couldn't see the point in going out and not going hard. Riding was a chore, and the fun part was being fit and having the day's ride over with.

Oh yes, Norm Alvis. You know about that. In an 11-mile race up Mt. Diablo in 1982, I passed him in the last tenth of a mile and beat him by thirty feet, and I have a picture to prove it. Back then and in later years he was famous, so that was the apex of my career. Does my telling you about it mean I still don't actually have racing out of my system? I DO.

BR: Tell us about your transcontinental bicycle trip in 1976.

Me and my then-girlfriend Jan rode it and had a great time. My bike was too small, hers was too big, and we holed up in Kearny, Nebraska for a week to rest and watch the Olympics. I started out on sew-ups and switched to clinchers in Jackson. Wyoming. I think mostly tourists and brochures call it "Jackson Hole," but it's the same place. We and everybody I saw that year -- the year of Bikecentennial -- rode with a huge handlebar bag and huge rear panniers. These days that's considered the worst possible way to load a bike, but it worked fine, and it's probably one of the reasons I don't always trust conventional wisdom.

BR: If you were living in California in the 1890s, what do you think you'd be doing for a living?

Give me a stout pair of boots and a shovel and some gloves, and tell me where to dig the ditch. I don't know. What would you do?

BR: How can the bicycle community (not the bike industry) set an example for the rest of the world regarding environmental stewardship?

I don't know that the rest of the world is looking this way. I don't think the lipstick-wearing, cigarette-smoking Parisians are looking our way, or the warmongers and oil-spillers, or even fans of "American Idol."

But the question is good and the topic can be interesting. There's a notion in the bike world that I don't totally buy in to, and that's the idea that if we "make a better commuting bike," people will start commuting by bike. Folks who believe this point to Amsterdam as an example. Clunky commuter bikes, lots of commuters. But Amsterdamers have short commutes and the infrastructure supports bikes by offering safe roads and giving bikes priority over cars in the intersections; and then really high gas prices and car taxes. You'd almost have to be insane or unable to pedal a bike to not ride a bike in that world.

Here we complain about gas prices even though they're the lowest in the world outside of that town in Venezuela where gas is something like $0.12 a gallon. Every now and then a reporter gets a bike commuter to say high gas prices drove him to it, but I'm sceptical. I think most people, shot full of truth serum, would agree that even $5 per gallon is a bargain for independent travel up to at least 60 miles, with all you can fit into a car, from delicate flowers and chandeliers to infants and elderly folks. Try doing that on a bike or on public transportation.

And that's why gas prices won't affect things much. Let me say, please, because I don't want to get in trouble with somebody who misunderstands what I'm saying. I'm for bike commuting, and in more than 35 years of working I have driven a car to work fewer than twenty times, even when my commute was 16 to 27 hilly miles one way, which it was for 20 years. But I wasn't doing that to be green, I was doing it because I've never liked driving and I wanted to stay fit. Those are personal payoffs, not philanthropic or far-seeing green ones, and I think that's the same for anybody.

A deferred consequence (like global warming) is a weak consequence and a bad motivator. To get people out of cars and onto bikes -- which I think is the best goal around -- takes more than cheerleading and $4 gallon cheap gas.

BR: If you were 30 years old in 2007, intent on starting a company, what would it be?

There are two ways to succeed, or two approaches that have a chance of it, anyway. You can be big or you can be small, and your size dictates what you do. If you're big you have to serve everybody, you have to be a generalist. Specialized started out small, sourcing and distributing truly specialized products that were hard to come by in the U.S., like Regina, Cinelli, and I think Campy was in there, too. But Specialized came of age at a time when the market was expanding so fast, and they went along with it and got big. They didn't get bad, they just got big. It's still a good company, but Generalized is a more accurate name than Specialized. They make "special" things in the sense that all bicycle things are "special."

But when you have your name on everything from après-bike sneakers to water bottles to clothing to bikes, tools, and accessories -- and one in five bike shops sells most of it, then that's not specialized in the dictionary definition any more. When you're that big, you can't afford to be. It would be like Safeway selling only organically grown food, or only vegan stuff, or only locally grown produce. If you're small, you can be specialized, and in the bicycle market in 2007, that's your only chance of surviving. You have to pick out something to sell, something to offer, that either can't be copied by people who have more money than you do, or is just not appealing to them -- maybe because they don't see a market for it, or because the only way they could promote it would be to position it against their bread-and-butter, which they aren't going to do.

For example, Trek could easily build lugged steel bicycles. They have before and could do it again. Not only that, but they could tie up all of our supplier's resources, so we couldn't get lugs anymore. Trek could hire any frame builders and run a loss-leading micro business with superfine handmade lugged steel bicycles for ten percent less than it costs to make them. But that's unlikely to happen, because what would it say about their other bikes? And they already have a Big Giant reputation, and people who like arcane bike stuff would rather buy from the hermit in the woods. It's part of the experience, and it's important.

Anyway, if I were 30 and starting out and for some reason had to have my own bike company, I'd pick something that was unattractive to big companies, and something that small companies who want to get big wouldn't copy or pay attention to. I'd pick something that most people thought was dumb, or didn't understand, and I'd sign in blood an oath to may family to never veer from that, to not be tempted by bigness or growth to do anything else. It would be one KIND of product. It might be more than one product, but it would be one KIND of product, and I'll even tell you what it would be: It would be a new wheels size, halfway between 650B and 700C. Right off the bat big companies have no interest, and small companies likewise just go, "huh?"

I don't use that as an example of something really dumb that nobody wants to do, and therefore it's somehow smart. No, I really believe in the size and I understand it, and if I were 30 (and my wife worked!) I'd focus my energies on explaining why it makes sense, and slowly cultivating some customers. I might do that, anyway, even now, but in some ways it'll be distracting from the other things we're doing, and if I were the floundering 30-year-old, it would be nice to have something like that to believe in and to focus on. When you're starting out, and maybe even always, you have to believe that what you're doing matters, because that's what gets you through the negative cash flow months and the hard times. If you're sitting around selling normal stuff that anybody can make and sell and sell it for less than you do, and nobody pretty much cares if you evaporate and are never heard from again, then it's hard to stick it out in tough financial times. So you need a mission that you believe in, and if you have that, it may not be a lot, but it's a small, powerful, black-hole of a thing, and that's what you want.

There are lots of opportunities out there, but not many people can get it together to commit and stick with it. How about a really nice frame pump that weighs 6oz and lasts a lifetime? It could cost $150. It could be made. Topeak can't sell $150 frame pumps, and neither can Zefal or Park or anybody else. But if all you made was ONE pump, in one colour, and it was metal and didn't have anything cheesy on it, and worked only with Presta valves, and used the best materials and was easy for the user to service, and came with a few small parts and good instructions and a lifetime registration card, and it complemented the look of nice bikes, then you could sell lots of them.

But people don't know where to start, and they worry about competition, and they're too tempted to cheapen it to get the price lower. It can't have laser-etching or silk screening. It can't have a lousy big logo. It can't have any plastic parts that are plastic because wood or cork or metal was too expensive. It doesn't have to pump to 120 psi faster than any other. It just has to look great, be made without compromises, weigh 6oz (maybe 7oz -- still two and a half ounces less than a Topeak or Zefal), and it has to work halfway decently. It has to be reliable and easy enough for most bicycle riders to use. Not 80-year old grannies, but 50-year-old weak guys.

Somebody could make a company doing that. There are at least ten other things I can think of, too.

Most people want to start a company, then sell out to a bigger company or license their things and rake in money on royalties. They don't want to actually work. They want to be "idea people," but everybody has ideas. People want other people to develop the ideas and do the real work, yet they want to be compensated for it. Ideas are cheap and everybody has them, but real work is hard and most people don't want to do it. That's what I tend to think, anyway.

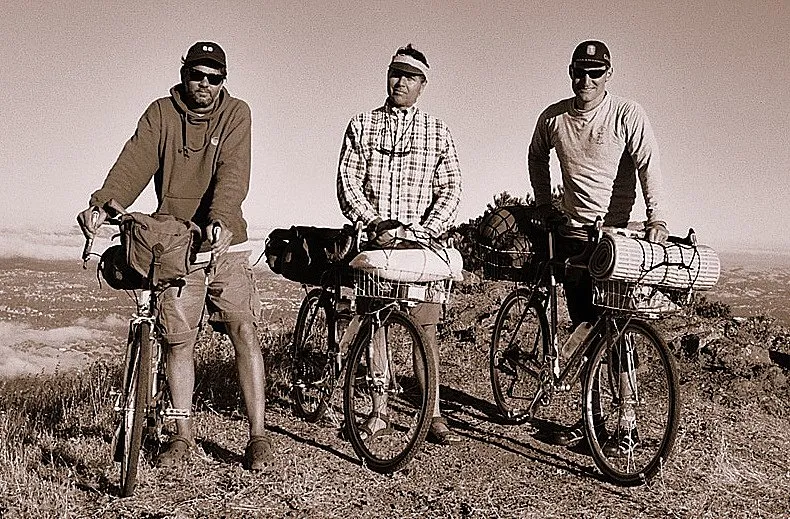

Look for more updates on the Rivendell Bombadil 650B mountain bike, my sub-24-hour camping trip with Petersen up the 3,400-foot Mount Diablo, and other fun things discovered in Walnut Creek.