Cannery Row in Monterey, California, has a colorful and checkered history. It was the inspiration and setting for John Steinbeck’s novel of the same name, and the street also stands as a cautionary tale of the dangers of overstepping nature’s limits – the cold, nutrient-rich waters of Monterey Bay fed the city’s booming sardine canning business until overfishing and pollution led to its collapse in the 1950s.

Gone are the canning companies that once lined this oceanfront street. In their place are posh hotels, seafood restaurants, kitschy tourist traps and one of the world’s finest saltwater aquariums.

But standing in stark contrast to the many new and renovated buildings is a former cannery that, for the past 23 years, has been home to light manufacturer Light & Motion.

The stench of sardines is – thankfully – long gone. What remains is an aging 7,000 square foot facility where Light & Motion’s 50 employees design and manufacture state of the art lighting systems for the dive and bike markets.

Bright beginnings

Light & Motion was founded in 1989 by a pair of Stanford graduates who were passionate about SCUBA diving and underwater photography. The numerous opportunities for mountain biking on the hillsides overlooking Monterey Bay made building lighting systems for mountain biking a logical next step.

In 1997, Light & Motion developed its first night riding system, the Apex 730D. While bulky and underpowered by today’s standards, this lighting system was ahead of its time, featuring two independently adjustable head units, a battery docking system and handlebar-mounted on/off switch.

A visual history of the company's products on show at Light & Motion HQ

The company was well positioned to take advantage of the surge in popularity in 24-hour racing in the late 1990s and early 2000s. Light & Motion helped a number of talented riders reach the top spot on the podium at many national and world championships. Some of the biggest names in endurance racing, including Chris Eatough, Rebecca Rusch, Nat Ross and Cameron Chambers, have ridden for the California company.

Shifting marketplace

Twenty-four hour racing had its time in the limelight, and there’s no denying that the popularity of these races has declined significantly over the past several years, a fact made clear by the cancellation of this year’s 24-hour World Championship race. For many endurance racers, 24-hour events have been supplanted by 100-milers and stage races.

There are still a number of popular regional events and a handful of iconic races, such as the 24 Hours of Moab and 24 Hours in the Old Pueblo. But few, if any, professional racers build their seasons around a full schedule of 24-hour events.

Lighting companies have felt the impact of this shift in racer preference more acutely than anyone, save for the promoters of these now defunct events. Thankfully for Light & Motion and its competitors, the decline has coincided with the growth of the high-end commuter market.

“Over the past several years there has been a significant shift in what cyclists are willing to pay for rechargeable lights,” said Light & Motion CEO Daniel Emerson. According to a survey conducted by Leisure Trends, a market research group that focuses on the outdoor industry, only 14 percent of all bike lights sold in 2010 cost more than US$100. By the fourth quarter of 2011 that percentage skyrocketed to 52.

As the number of dedicated commuters grows, so too does the need for quality light systems.

Form and function with Roxy Lo

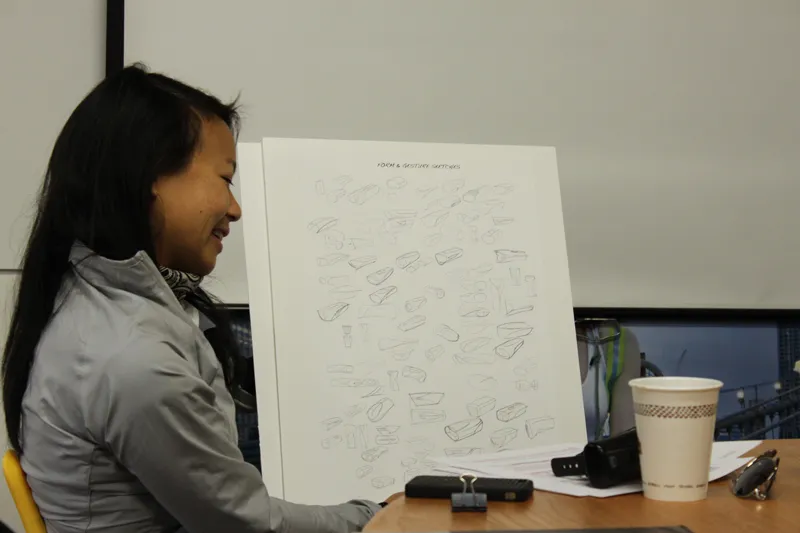

Industrial designer Roxy Lo might be better known for her work in creating the curvaceous lines of Ibis’ Mojo family of mountain bikes. But for the past five years she’s also had a hand in designing all of Light & Motion’s products.

Lo going over some early sketches for the Taz headlight

A big part of Lo’s job is batting ideas back and forth with the company’s engineers, trying to meld her design concepts with practical considerations such as the integration of heat sinks and placement mounting brackets.

Light beams over lumens

Currently, Light & Motion’s highest output model is the Seca 1700. While outclassed by as much as 50 percent by the claimed output of other brands, Light & Motion feels it can go toe-to-toe based on actual output – according to their tests this can be as little as half of claimed output. The brand focuses on developing lights with a quality beam pattern.

“Many companies use off-the-shelf parts, some of which were actually designed for halogen bulbs. There’s a lot of wasted light, halos, bright and dark spots,” said Emerson. All of these “flaws” in a beam pattern can diminish a light’s effectiveness in lighting the road or trail.

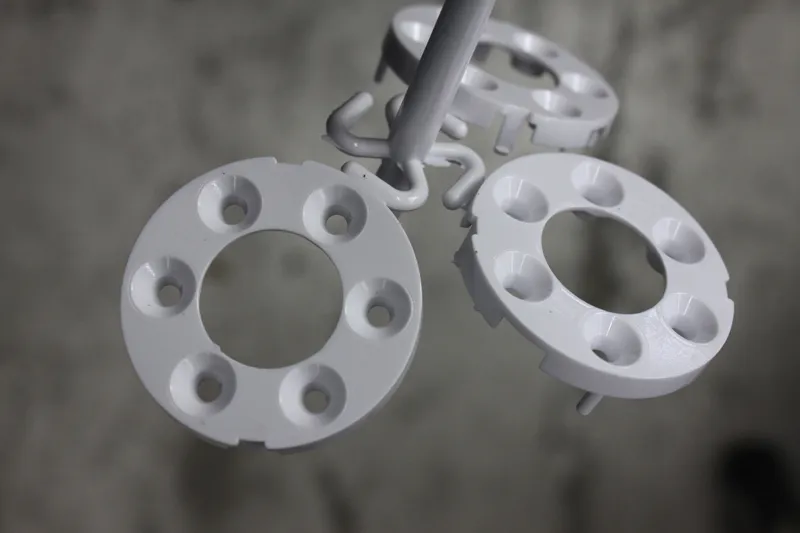

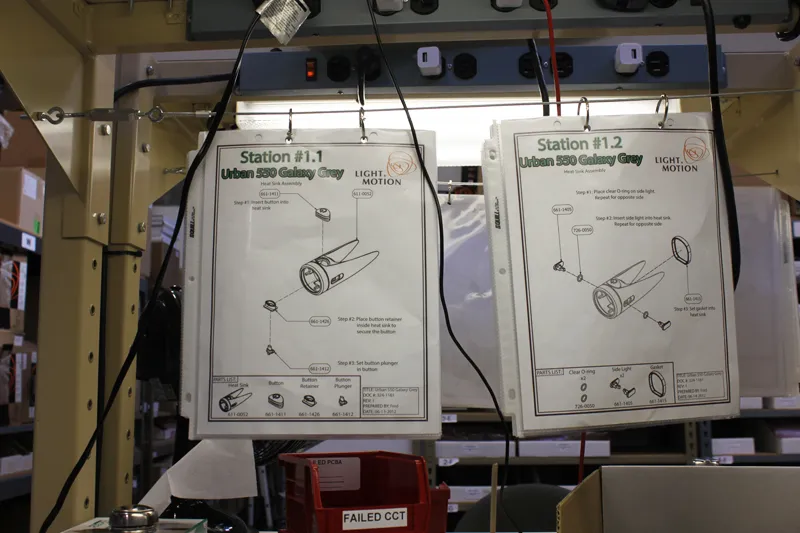

Emerson is passionate about keeping as much of the company’s manufacturing stateside, and feels that by designing and building in-house Light & Motion is able to place a greater emphasis on the quality of the beam pattern through intensive prototyping.

Keeping the competition honest

Light & Motion is not a leader when it comes to raw output, at least not on paper. The company recognizes that the calculus consumers employ when purchasing a light generally centers on the ratio of lumens per dollar.

The problem for customers is that, until recently, there were no standards for claimed versus actual lumen output. Companies can essentially make whatever claims they want about the brightness of their lights, with no third party testing to hold them accountable.

In an effort to level the playing field, Light & Motion has embraced the FL-1 lighting standard, which sets guidelines for testing brightness and five other criteria for performance. BikeRadar will have more on the FL-1 standard in an upcoming article.