The Forbidden Druid is a sleek, carbon trail bike which uses a suspension system that has so far been more-or-less reserved for downhill bikes.

- Best mountain bike: how to choose the right one for you

- Mountain bike groupsets: everything you need to know

By placing the main pivot high above the chainring and routing the chain up past the pivot with an idler pulley, its high-pivot arrangement claims superior bump absorption and minimal interference between the chain and the suspension for a smoother ride.

High-pivot bikes have proven themselves on the world cup downhill circuit, having been ridden to victory at four out of the last seven men’s races. But high-pivot bikes have a reputation for draggy and lazy pedalling, so few would consider applying this illustrious layout to a trail bike.

But Forbidden has done just that. The Druid sports only 130mm of rear wheel travel and is claimed to be an efficient, poppy trail tool, not a gravity-hungry sled.

But does the high-pivot and short travel combination make sense? I’ve ridden one to find out. But first, let’s talk about the bike.

Who is the Forbidden Bike Company?

Forbidden Bike Company comprises, among others, Owen Pemberton, who played a key role in the development of Norco’s HSP downhill bike — which also uses a high single pivot suspension design.

After leaving Norco he became involved in a start-up bike brand, now known as Forbidden. Apparently, the company name derives from the Forbidden Plateau near Pemberton’s home in Vancouver Island, Canada, where he rides and tests regularly.

Why high pivot?

According to Pemberton, the goal was always to design a short travel trail bike, but the high pivot design didn’t immediately spring to mind. “The process involved exploring a bunch of different suspension designs, starting from a clean slate”, Pemberton explains. “I actually nearly went down a low (linkage-driven) single pivot route.”

When asked why single pivot over four-bar, Pemberton gave a surprising answer: “I enjoy how simple the manufacturing process is when you’re working with two big pieces of carbon … you can get very good frame alignment… so the bike lasts longer.”

He went on to explain that with four-bar bikes, tight tolerances can be more expensive to maintain, while with linkage-driven single pivots, the links that control the leverage on the shock can be easily changed without redesigning the whole back end.

When I asked why he ditched conventional single pivot in favour of a high single pivot, again he gave a surprising answer: “I’ve got short legs and I like riding a 29er. I’ve found that to get a 29er to fit smaller people you have to get that back end tucked right in, and to do that you can’t put a tube in between the chainring and the tyre. You’ve got to go up and over. The high pivot lends itself perfectly to that.”

He went on to say, talking about suspension kinematics that “everything’s a compromise, but the high pivot allows me to get the best compromise.”

High pivots 101

At this point, it’s worth explaining the theory behind high pivot suspension in more detail. If you’re not into suspension kinematics, perhaps skip to the next section. If you’re very interested, you may want to take a look at this article too.

Usually, the height of the main pivot is limited by the chain; if it’s significantly higher than the top of the chainring, the upper chain line will extend as the suspension compresses, which is known as chain growth.

Chain growth is not too problematic when the freehub is free to rotate clockwise, spooling out chain to the upper chain line as the suspension compresses. However, during fast compressions, or when the rear wheel is locked up, the freehub cannot rotate fast enough, so instead the crank is forced to rotate backwards. This is known as pedal-kickback. This causes uncomfortable feedback to the rider and inhibits the suspension’s ability to move, particularly when pedalling.

By using an idler to route the upper chain past the pivot, high pivot bikes can eliminate the upper chain growth problem altogether. At the same time, this allows a higher pivot placement which would otherwise be prohibited by chain growth.

This has a couple of key advantages.

First, a high pivot dictates that the axle arcs rearwards, as well as upwards, as the suspension compresses. When the wheel hits a bump, the force it exerts on the wheel has a rearward component. The direction of the force is the same as a line drawn from where the bump contacts the tyre through the axle. So the bigger the bump, the more rearward the direction of the force.

A rearward axle path therefore allows the wheel to move roughly parallel to the direction of the bump force. The axle also moves further round its (rearwards) arc than it moves vertically.

This means that bump forces (pushing parallel to the axle path) have more leverage over the shock than vertical forces, such as the normal reaction force which holds up the rider’s weight. This effectively makes the suspension softer over bumps, without sacrificing support when pushing into the ground.

Second, the axle path provides an anti-squat force that acts to minimise pedal-bob. This is because, when pedalling, the driving force pushes the rear axle forwards; as the axle is underneath the main pivot, this force acts to extend the suspension, countering its tendency to compress due to pedalling-induced acceleration.

High pivots do have some downsides though. Most obviously, they require an upper idler pulley and usually a second pulley behind the chainring to provide enough chain wrap.

These add drag and potential maintenance issues, as well as requiring an extra-long chain. Secondly, the lower chain line (from the derailleur’s lower jockey wheel to the chain ring) lengthens considerably as the suspension compresses, which may cause wear on the derailleur.

The high single pivot design also results in high levels of anti-rise, which is traditionally associated with a harsh feeling under braking. However, this is not the case in my experience with high-pivot bikes.

Forbidden Druid details

Suspension

According to Pemberton, the Druid is designed to have around 120 percent anti-squat at sag. In theory this means it should pedal efficiently, particularly when pedalling out of the saddle.

The idler is offset behind the main pivot to increase anti-squat. According to Pemberton, there is a small amount of upper chain growth as a result, but not so much that you’re likely to notice any pedal kickback.

The shock is driven via a rocker link which is pulled from the bottom of the swingarm. Apparently, the linkage is progressive towards the very end of the stroke, but not so much in the mid-stroke.

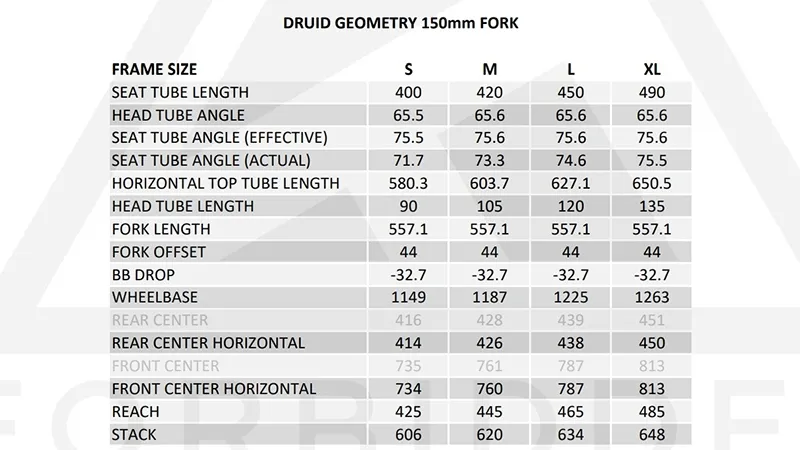

Geometry

We’ve so far talked much about the suspension, but the Druid’s geometry is very interesting too.

The rear centre length is different on each frame size, growing by 12mm between each. Ingeniously, this is achieved not by lengthening the swingarm (which would require size-specific swingarms and affect the suspension travel) but instead the bottom bracket moves forwards relative to the main pivot as you go up the sizes.

This means the ratio of the front-centre to rear-centre (which affects the front to rear weight distribution) remains near-constant throughout the range. Compared to bikes with the same rear centre, this should make it easier for short riders to manual and hop, while providing more front-wheel traction to those on longer bikes.

As Pemberton puts it: “Yes, the chainstays are size specific, but the goal is that the handling of the bike stays the same… everybody who doesn’t change the chainstay length has size-specific weight balance!”

The Druid’s rear-centre goes from 414mm (small) to 450mm (XL). That’s a difference of 36mm, or 8.7 percent. Over the same size range, the front-centre grows slightly more (10.6 percent).

By comparison, the YT Capra also boasts size-specific rear-centre lengths. But they change by just 5mm (1.1 percent) between the smallest and largest frame sizes, while the front-centre grows by 8.9 percent.

It’s worth noting that the rearward axle path means the rear-centre will grow significantly as the suspension compresses, so the back end will feel longer than these numbers suggest.

In addition, the actual seat tube angle gets steeper in the larger frame sizes. This is to counter the effect of the offset seat tube, which otherwise makes for a slacker effective seat angle the higher the saddle height.

According to Forbidden, the effective seat angle (the angle of a line between the bottom bracket and the top of the seatpost) is the same for each frame size.

Combined with the longer rear-centre, this should help tall riders to achieve a nicely centred weight distribution when climbing.

Forbidden Druid ride impressions

Forbidden doesn’t have any XL bikes right now, so I rode a large, which is smaller than I would choose. On the other hand, I was able to ride it on trails I know well in the Forest of Dean.

While the size large was too small for me, it’s well proportioned. The 465mm reach and 65-degree head angle may not leap off the page these days, but remember this is a trail bike. The main problem I had was that I couldn’t get the bars high enough. Looking at the geometry of the XL, with its longer reach and taller stack (which effectively makes the reach longer still) I think it would have suited me well.

The most important thing to say is that this bike does indeed pedal well. Back-pedalling the cranks by hand does reveal some noticeable drag, but when riding, this doesn’t seem to be significant. Familiar climbs and tedious fire-roads were dealt with at least as painlessly as I would expect with similar bikes. Of course, this is not a scientific test of drivetrain drag, but I didn’t “feel” anything holding it back on the short ride.

In fact, the Druid climbs well. The suspension doesn’t bob much at all, especially when seated. It stays on top of its travel nicely even when climbing steep gradients.

The 76-degree effective seat tube angle is not the steepest, but with that supportive back end, it’s steep enough. Best of all, the suspension works well even when putting a lot of power through the pedals. Traditional bikes with efficient pedalling platforms (more than 100 percent anti-squat) become firm and hang up over bumps when pedalling, but not this one.

When descending, it soon became clear that the high pivot design didn’t make the Druid a downhill bike. In fact, it felt a bit sticky over small bumps to begin with. Perhaps I was expecting too much from a 130mm back end, but once I’d opened up the shock’s compression damping fully and sped up the rebound a little, it came to life.

It’s still not going to steamroller over all in its path, but the back-end tracks well and never hung up on big holes or roots. It’s quiet too. I didn’t have the chance to ride over chunky rocky terrain, but I suspect the suspension would excel there.

The high single pivot suspension seems to hunker down under braking, helping the bike to stay low and slack even when braking hard on steep chutes. This feeling may not be to everyone’s tastes, as the back end may feel heavy over braking bumps, but it allows for aggressive, late and hard braking into turns.

Similarly, the fact that the rear of the bike lengthens as the suspension compresses is noticeable and takes a little getting used to. But, perhaps because I’ve ridden a couple of high pivots before, or perhaps because the Druid simply doesn’t have that much travel, I found it quite intuitive after a couple of runs.

In fact, the back-end extending as the bike is loaded up into a turn seems to settle the bike into the corner and shift more weight onto the front contact patch, delivering fantastic mid-corner grip. The low bottom bracket helps here too.

Do high pivot trail bikes work?

Yes. The Druid pedals efficiently while absorbing bumps brilliantly. It descends well for a short travel bike too. But that doesn’t stop me wondering just how good a longer travel, more aggressive version could be.

Forbidden Druid high-pivot trail availability and pricing

The Druid is only available as a frameset, including Fox DPX2 shock, axle, frame protection and E*13 upper and lower chain guides. It will retail for £3,150 / $2,999 / CAN$3,999.

Forbidden Druid high-pivot trail bike geometry

- Size tested: L

- Sizes available: S, M, L, XL

- Seat angle (effective): 76 degrees

- Seat angle (actual): 75 degrees

- Head angle: 66 degrees

- Chainstay: 43.9cm / 17.28in

- Seat tube: 45cm / 17.72in

- Top tube (horizontal): 62.7cm / 24.69in

- Bottom bracket drop: 3.6cm / 1.42in

- Wheelbase: 1,221mm / 48.07in

- Stack: 63cm / 24.8in

- Reach: 47cm / 18.5in

For more, visit Forbidden Bikes