This Saturday (19 September) sees the Tour de France tackle one of the most interesting time trial courses we’ve seen for a long time.

Though the quantity and importance of both individual and team time trials has been dwindling in recent years, this one has the possibility to really upset the apple cart.

The opening 30km is standard Grand Tour time trial stuff, but in a wonderful twist (for us viewers, perhaps not so much for the riders), the race organisers have decided to tack a mountain top finish onto the end of it, meaning tech choices will be more important than ever.

With that in mind, we asked aerodynamics and time trial expert Xavier Disley, of UK-based performance specialists Aerocoach, to give us his insight on the challenges the riders and teams will face.

Of course, it helps that we’re going into it with a relatively close general classification battle between the current leader, Primož Roglič of Jumbo-Visma, and Tadej Pogačar of UAE Team Emirates.

At the time of writing (and barring any incident on stage 19), only 57 seconds separates the two Solvenians. Though Roglič is a time trialist of considerable quality – he’s previously won time trials at both the Giro d’Italia and the Vuelta a España, and finished second in the World Championships time trial in 2017 – Pogačar actually beat him to take the Slovenian national time trial championship back in June 2020.

Regardless of whether Pogačar can overturn the deficit (a time-trial 20 stages into a Grand Tour is very different to a single day event, after all), the course profile means this promises to be an incredibly interesting day from a tech point of view too.

Related reading…

The course

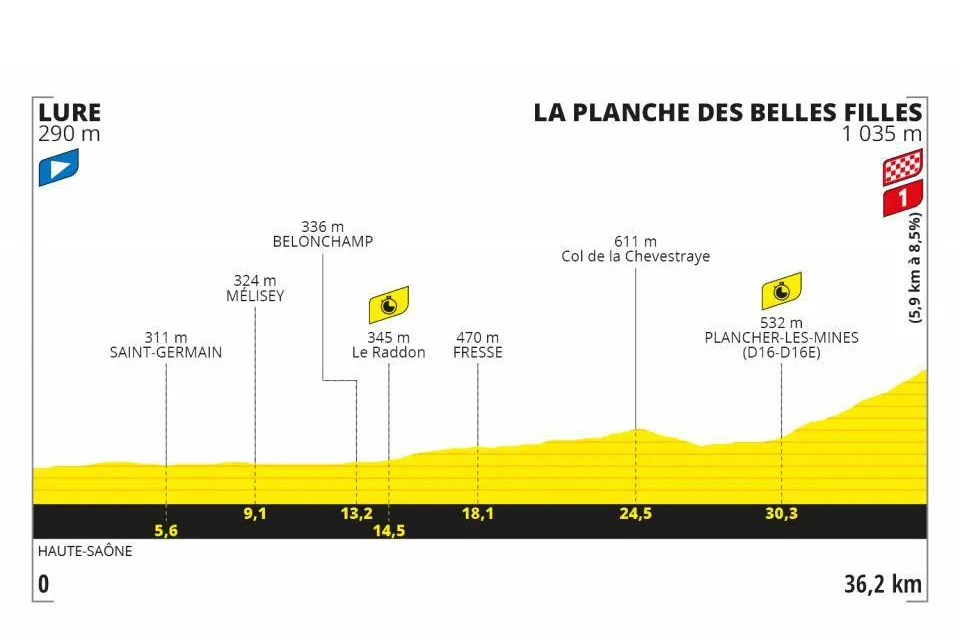

Starting in Lure, the 36.2km course consists of a fast, flat section in the opening kilometres, followed by a gentle climb and descent, and then a proper summit finish at La Planche des Belles Filles.

Though there have been plenty of flat time trials and quite a few mountain time trials in the Tour’s long history, there haven’t been many that have combined both to such a degree.

For those not familiar with the climb, it might not be the Galibier, but at 5.9km in length, at an average gradient of 8.5 per cent, it’s an extremely stiff test for an individual time trial at the end of a Grand Tour.

Consequently, kit choice will be crucial because riders will need to optimise their aerodynamics, weight and rolling resistance to achieve their best performance.

While a standard time-trial setup will be the obvious choice for the opening part of the stage, the prospect of a significant climb to finish makes the extra weight involved with all of that aerodynamic kit decidedly less appealing.

Of course, how hard a rider can turn the pedals will also make an enormous difference, but when the biggest race of the season is on the line, the best teams will be leaving no stone unturned.

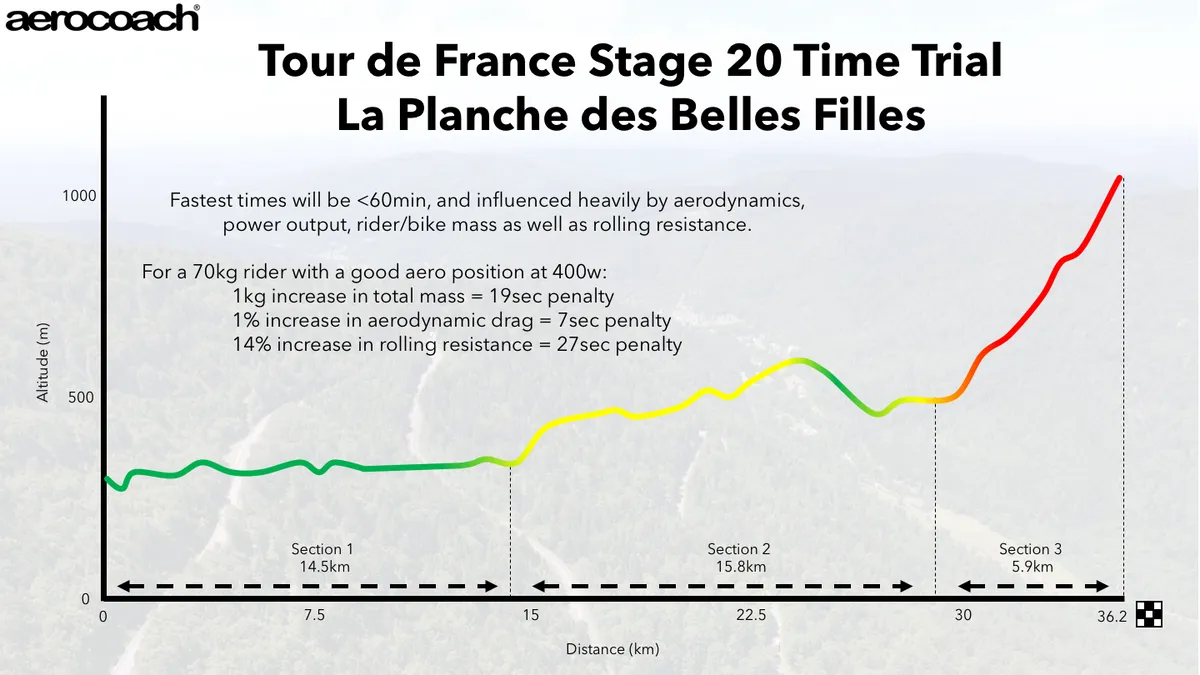

Predicting that the fastest times will be under 60 minutes, Disley explained how differences in weight, rolling resistance and aerodynamics could also affect a rider's time.

Weight

Professional riders and teams are used to cutting weight – making stuff lighter continues to be a key tech trend at the Tour de France – so we’ll almost certainly see some creative solutions to getting those (relatively) heavy time-trial bikes as close to the 6.8kg weight limit as possible.

The riders themselves will also look to be as light as possible, with food and fluid intake clearly pre-defined to further minimise weight and maximise performance.

“Aerodynamics are, of course, paramount with any time trial,” says Disley, “but here, both rider and bike weight are going to have a significant impact on the race too.

“For a 70kg rider, with a good time trial position and a 400w power output, a change in mass of 1kg will have a minimal impact during the section to the first time check – just a two-second time penalty.

“The second part, which includes the climb of the Col de la Chevestraye, is slightly more of an issue, with an increase of 1kg resulting in a four-second penalty.

“But the final climb is where it matters most. There, an increase in mass of 1kg results in a 13-second penalty. This adds up to a total of 19 seconds lost over the entirety of the course.”

A not insignificant amount, but perhaps not as much as we might have guessed.

Maybe it would be better to switch to a road bike at the bottom of the final climb to save weight? Disley’s not so sure.

“Assuming a flawless bike swap takes around 8 seconds, then including the time taken to slow down and then regain full racing speed, you’d need the road bike to be at least 1.7kg lighter than the time trial bike to make it worth it,” he says.

Nevertheless, some riders may choose to swap to a road bike simply so they can climb in a position in which they’re most comfortable and able to produce the most power in.

There’s always the chance that, in the heat of the moment, something will go wrong with the bike change though, so riders and teams will have to weigh up the risks and rewards of either choice.

Rolling resistance

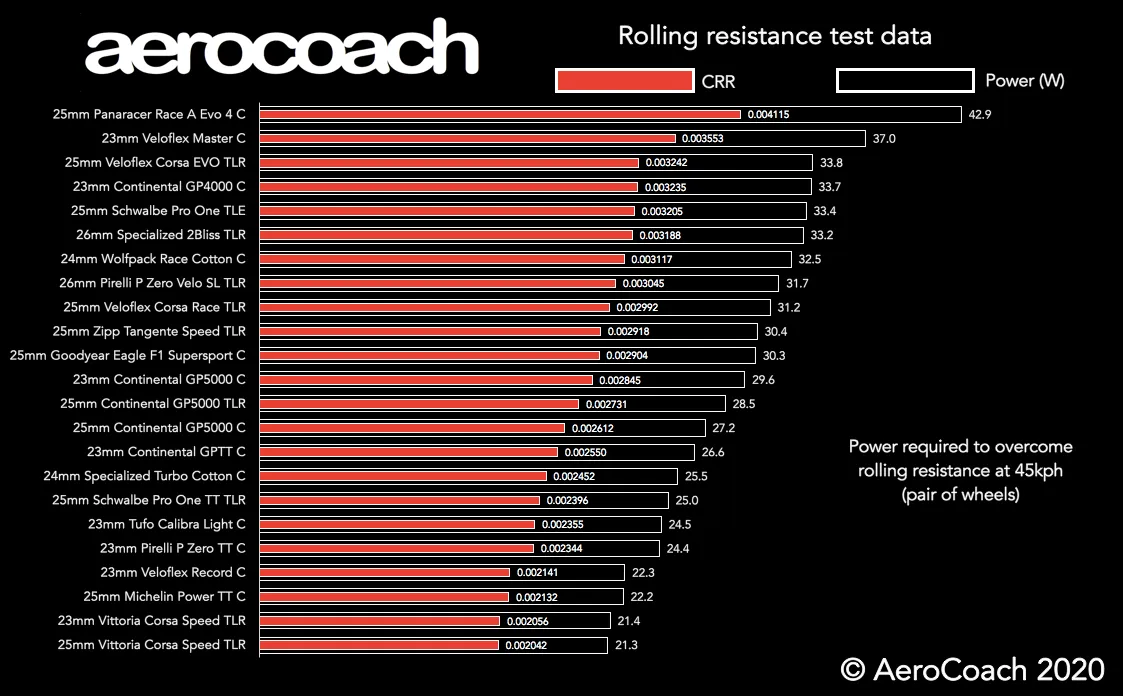

According to Disley, tyre choice will be crucial, and arguably more important than weight.

“According to our data, a rider using Vittoria’s Corsa Speed tyres will save around 27 seconds over a rider using Continental GP5000 tyres, for example, because of the small difference in rolling resistance,” he says.

“Professional riders and teams are, of course, governed by sponsor commitments, but will nevertheless be looking to use the best kit they can to achieve the lowest weight and highest performance.”

The latter is more of an issue for some teams than others, though.

We’ve seen big teams such as Ineos Grenadier and Jumbo-Visma openly using non-sponsor correct wheels both during and before this Tour, for example.

Other teams may have to be more subtle though, so we can perhaps expect to see liberal use of the professional mechanic’s best friend, the black magic marker.

Aerodynamics

While there will no doubt be a huge obsession over weight given the final climb, Disley warns that riders and teams shouldn’t neglect aerodynamics. It is a time trial, after all.

The majority of the course is either flat or rolling, where aerodynamics will arguably be the key factor in determining a rider’s performance.

Trading heavier, but more aerodynamic components for lighter, less aero ones needs to be done strategically, Disley says.

“If a team wanted to use lighter components that were less aerodynamically efficient, a 1% increase in aero drag must be combined with at least 400g of weight savings for there to be a net benefit.

“If you can’t get 400g of weight savings, keep the aero kit.”

The optimum setup

What is the optimum setup then – a time trial bike with super-light, but still aero wheels and components?

“I would choose a full time trial bike with a disc wheel”, Disley says, “and probably a tubeless version to mitigate the risk of punctures compared with a tubular pair of wheels (you can get very lightweight tubeless wheels these days).

“Choose the fastest rolling tubeless tyres you can possibly use, and get the black marker out if needs be. Apart from that, don’t make any aero concessions – it’s just not worth it unless you can get big weight savings.”

Disley also has some last minute tips for riders desperately looking for an edge on the competition:

- Consider whether you really need a drink for a 1-hour effort. Ditching the bottle and bottle cage will be both lighter and more aero (our testing tends to show even aero bottles can still be an aerodynamic penalty). A 100g bottle and cage with 200ml liquid that increases aero drag by 1 per cent will be overall a 13-second penalty.

- Raising the base bar (while keeping the aero extensions and armrest pads in the same place) will give a more upright and more powerful riding position for the final climb, when you won’t need the extensions anymore.

- If your time-trial helmet has a visor, chuck it at the bottom of the final climb. It’s a tiny weight saving, but more crucially it will help stop you overheating.

- Tyre pressure is just as important as tyre choice. Traditionally, professional teams have tended to use very high pressures, but we’ve found that lower pressures (especially as part of a tubeless setup) are more efficient. Over-inflating your tyres could cost you as much as 5 watts.