We first came across Torgny Fjeldskaar’s work at the world’s biggest bike show, Eurobike, back in the early 2000s at one of Cannondale’s mega-stands, which was showcasing a cutting-edge concept bike.

The radical geometry-shifting machine on display was a bike that could morph from a flat-out time-trail machine into a more upright comfortable one. It was space-age stuff, so I set out to meet the team behind this amazing flight of fancy and through one of our Cannondale contacts were introduced to Norwegian industrial designer Torgny: a quiet, softly spoken, focused man.

After explaining his initial thinking when designing the bike he then delved deeper into the influences in his designs – which ranges from cars, to aircraft and even chairs.

After many years following Torgny’s inspiring Instagram feed (@torgny_f), which showcases his incredible designs and hand-drawn artwork, I decided to catch up with Torgny to find out more about the industrial designer’s role in bike design, discuss how the industry has changed over the decades and take a closer look at some of his fascinating sketches.

About Torgny Fjeldskaar

Having held design director roles at Cannondale and BMC, Torgny has had a significant role in the design of some of the most iconic – and much-loved – bikes of the past couple of decades, including the Cannondale SystemSix, Cannondale Hooligan and BMC Teammachine. Bikes that aren't just great to ride, but look great and set the pulse racing, too. With carbon fibre and the latest engineering advancements allowing for increasingly complex bikes, the role of the industrial designer is more influential than ever.

BikeRadar: How did you get started in the world of designing bikes and was this the vehicle you always wanted to focus on?

“I got my first bike at the age of five and it’s been my main mode of transport ever since. For many years I was a paperboy so I got used to riding in all sorts of Norwegian weather early on. You basically get as wet as in the UK but quite a bit colder!

"At the age of 10, I got my first road bike, and as a teenager I got into the-then big, new trend of mountain biking and later on some gravel touring (except we didn’t know it was called gravel at the time). I always loved the design simplicity of bicycles and conversely the changes that mountain bikes brought.

“Bicycles are such a big part of my life that it wasn’t until the age of 33 I bought my first car, a vintage BMW 323i from 1980. As much as I love cars, in my opinion, they make little sense as a daily means of transport in urban areas.

“I studied mechanical engineering in Trondheim, Norway and then I did a masters in transport vehicle design in Barcelona for two years. My first job after graduating was in automotive design at Mazda’s European Design Centre in Frankfurt, a place I really enjoyed working and I learned a lot from helpful colleagues.

“Next stop was Cannondale Bicycles, a company I hugely admired as a teenager when I first got into mountain biking. Cannondale offered me the chance to lead the industrial design (ID) efforts on its urban bikes, which was unchartered territory for the company and was aimed primarily at the European market.

"After a year or so I was promoted to director of industrial design: the entire bike line. At 28 I knew this had clearly come a bit too early in my career, but at the same time it’s an opportunity you can’t turn down! I stayed at Cannondale for almost six years, I got to work on lots of cool projects with some truly great people and then I decided to move on as I was keen on learning new things and developing as a designer.

“Then I fulfilled another childhood dream and got a job at BMW in Munich in the exterior design team for production cars. Working with so many talented colleagues was both humbling and incredibly inspiring and I really had to raise my game on many levels.

"It was so cool to go to work and soak in new knowledge every day! Little by little I found my feet and got more responsibility, but after a while in the position of creative director of detail design for the compact vehicles, I ended up having so many meetings I had little time for design and I was [so] far away from the product that I decided to move on and go back to my first love: bicycle design.

“The next opportunity came about shortly after at BMC Switzerland, where I had the unique opportunity to build an in-house design team from scratch, develop a new design strategy and implement it over a period of five years.

"In terms of what I could influence myself and what we could achieve with the design, and engineering group, this job certainly was the highlight of my career so far! The only big issue was a terribly long (rail) commute of one and a half hours, door-to-door each way, so when we had our second child it started to become unbearable and I left the company to start my own design studio in Basel, where I now work for various clients, but mainly in the bicycle industry.”

01 / BMC: “The Impec Concept (2014) was the first project I got to work on at BMC. The idea was to imagine what a road bike could be five to seven years from then.”

- Read more: BMC Impec Concept machine revealed

02 / BMC: “The Impec Concept had a modular approach. You could, for example, choose between a Pinion-style gearbox or electric assist. The structural frame itself actually had nothing integrated inside it, but all the non-structural add-ons completed the aerodynamic shape.”

BikeRadar: What has changed in bike design and manufacturing since you first started working in the bike industry?

“When I started at Cannondale back in 2003, game-changing materials and processes, such as carbon fibre and hydroforming were just taking off and this obviously had a massive impact on our industry.

"Prior to this, there wasn’t much work done by industrial designers on bikes; frame design was, for the most part, welded, round tubes created by engineers, plus some decals (transfers) done by the graphic designers. Now all of a sudden you could pretty much shape things the way you wanted, so most large bicycle companies started hiring industrial designers, and you began seeing some heavily shaped frame designs out there... not always supporting the intended purpose of the bike, though.

“During this period at Cannondale, we held back on crazy shaping for a number of reasons. The approach was more engineer-driven and, as much as my team and I would have liked a bit more freedom, in retrospect, this probably wasn't a bad thing.

"As far as road bikes go, integration was at a very different level than today. The focus back then was mainly on stiffness-to-weight and if you had a custom stem and some colour-matched parts and decals, you already had a visual advantage over many of your competitors.

“In the mid-00s, comfort on road bikes also started becoming a thing, although it was called compliance or vibration-damping in order not to alienate the hard-core roadies. Frame and component designs have improved vastly on vertical compliance and comfort over the last 15 years and, to some extent, it’s become relevant even for the pros.

"Another thing that has improved is computer simulations, both for structural and for aerodynamic optimisation. Today, these tools are far more sophisticated and accurate, and help in reducing development time. The flipside is that frame designs are more similar than in the past – very few stand out in terms of shapes these days, it’s become more about details and how tubes are connected.

A few other big changes worth mentioning are aerodynamics, disc brakes, wider tyres and electronic shifting – all of which have benefits that for many people outweigh the drawbacks, and they’ve obviously all had a huge impact on frame and fork design. To me, the biggest question when it comes to innovation is why on earth road bike tyres were so narrow for so long. I mean, road surfaces are often bad nowadays but I’m pretty sure they weren’t better 50 or 100 years ago!

“On the topic of integration, at BMC we had a strong focus on cleaning up the aesthetics while still providing great performance, and I’m proud of having been part of pushing this trend. The fact that so many brands have followed suit shows that it’s something many end customers really do appreciate.

“One more thing that has changed quite a bit is the complexity of the projects, so now there are typically more people involved. For example, a new cockpit is a big project in itself these days, and then you have the CAD (computer-aided design) modellers who now do part of the job the engineers and designer used to do.”

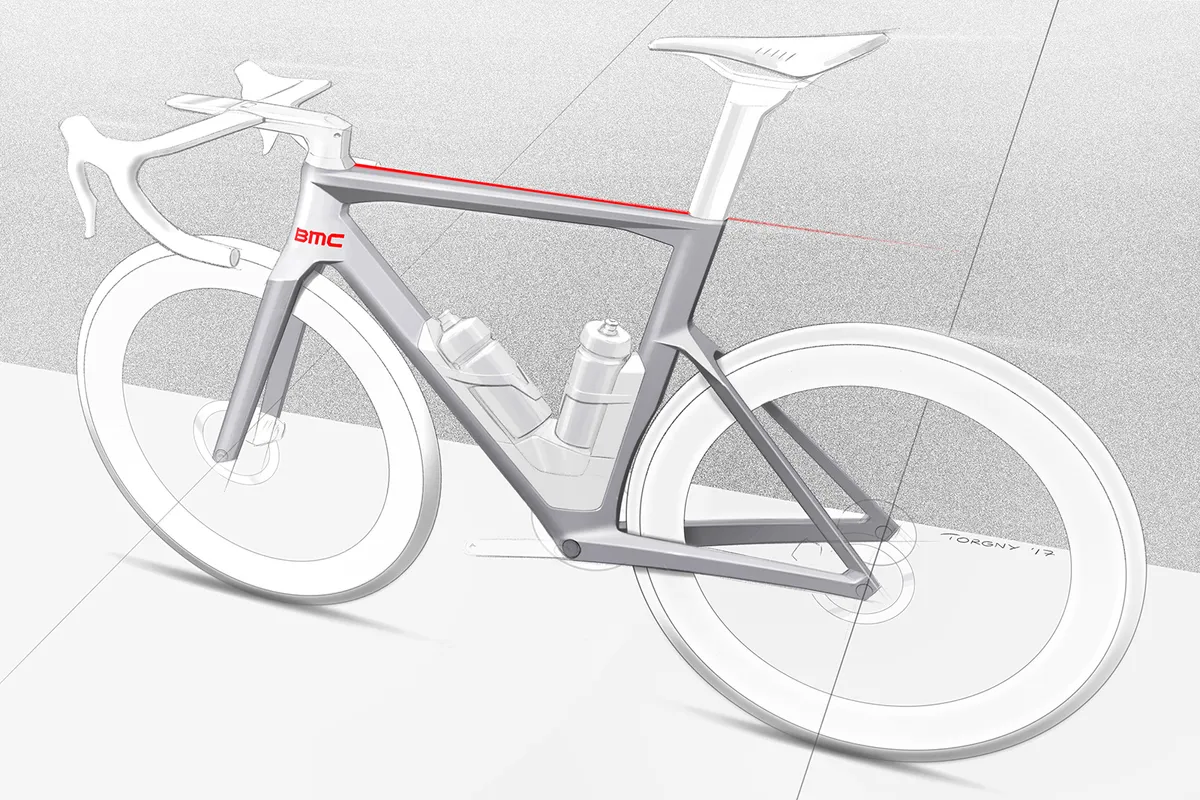

03 / BMC: “The Timemachine Road Gen 2 is one of the coolest projects I’ve ever worked on as we got to do a completely new aero cockpit and aero bottle cages. The bottle cages and storage create a flush aero section surface and help reduce drag.”

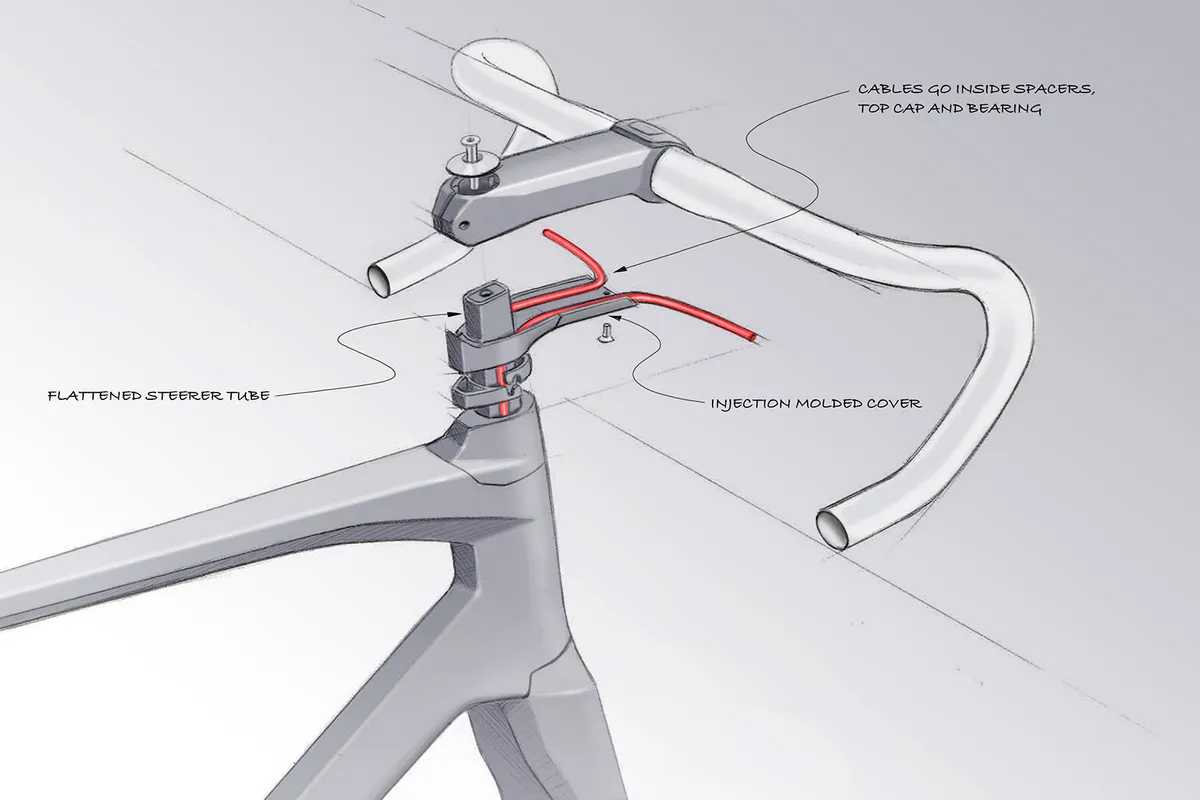

04 / BMC: “The Teammachine SLR01 (2017) was a first in the altitude/racing category in terms of cable integration. Some people were sceptical as to how much of this was relevant for ‘proper’ roadies, but sales numbers certainly proved them wrong.”

05 / BMC: “The Integrated Cockpit System (ICS) is a feature that has aero and, obviously, visual benefits, and something that’s easy to propose for a designer. The hard part is the engineering. The engineers did countless hours of constructing, testing and refining prototypes, so most of the credit goes to them!”

BikeRadar: Having designed for such a broad spectrum of brands and aspects of the bike, how do you see the role of the industrial designer?

“As an industrial designer, you are given a design brief (most often from the product managers) with lots of input on, for example, who the target customer is, what this new product is supposed to do, main competitors etc. On top of that you get a lot of input and constraints from the engineers, such as geometry, clearances and tube sections.

"The industrial designer then creates a number of different 2D or 3D proposals within this framework, always trying to come up with nice shapes, and new and fresh design cues, while at the same time keeping an eye on the company’s design strategy in order to have a certain recognisable look and feel across the product portfolio.

“When selecting proposals for further development, you’d typically have a number of stakeholders involved: design, PMs (product managers), engineering, sales, marketing, CEO etc, and due to the subjective nature of the topic it can sometimes take a long time to reach an agreement!

“Once a direction is chosen the role of the industrial designer is to assist the engineer in bringing the design to production. Some things may have to be changed and then it’s all about making sure those changes don’t ruin the looks completely. In some cases, you have a conflict of interest when it comes to design refinement versus timeline or looks versus performance, but in most cases, the priorities for a given segment are pretty clear and the product manager is usually the voice of the end customer in case there’s a disagreement. For the most part, the collaboration tends to work out really well though, as everyone involved understands that both engineering and ID goals need to be met in order to end up with a successful bike.

“Another question I often get asked is the difference between the automotive and bicycle industry. In the automotive world you tend to have more and better processes in place, and in general everything’s more organised, although in recent years the bicycle industry has made big improvements in these areas, for good and bad. The chaos has definitely been reduced but, sadly, also some of the spontaneity, partying and the laid-back approach has too.

“Another big difference is the role and status of industrial design. In the automotive industry, the designers are celebrated superstars, think Ian Callum (Jaguar), Chris Bangle (BMW), or legends such as Giorgetto Guigiaro (Ferrari 250GT) and Battista Farina (Ferrari 212, Dino, Alfa Romeo Duetto).

"In the cycling industry, the industrial design plays a much smaller role in the official marketing story of new products. In the end, I think it’s not a bad thing as the truth is that it means nobody becomes a bike designer to achieve fame and fortune, it’s very much a passion-driven profession, and I believe this is one of the reasons that there’s such a great vibe in our industry.”

06 / “The Pinarello Espada Tribute is just a sketch I did as a tribute to Miguel Induráin’s world hour record rig from 1994. The original was one of the bikes that made me want to become a bike designer (along with Chris Boardman’s Lotus 108 and some of the crazy MTBs in the early 90s).”

07 / “The DH Concept is another random bicycle sketch, which I really enjoy doing if I find the time. And I also try to encourage other designers to put more bike sketches out there, because for every bicycle sketch there's a million car sketches on the internet, and if we want the next generation of creative talent to dream of designing bikes instead of supercars, we have to change that!”

BikeRadar: The fact that bringing a bike design to reality is a hugely collaborative effort is perhaps the reason that bike design doesn’t have many stand-out names as the ‘authors’?

“It’s very important to point out that I’ve only done the industrial design on these bikes – it’s always a team that does the complete design and if these products ended up being successful it’s because I’ve been lucky to be part of some truly great teams.”

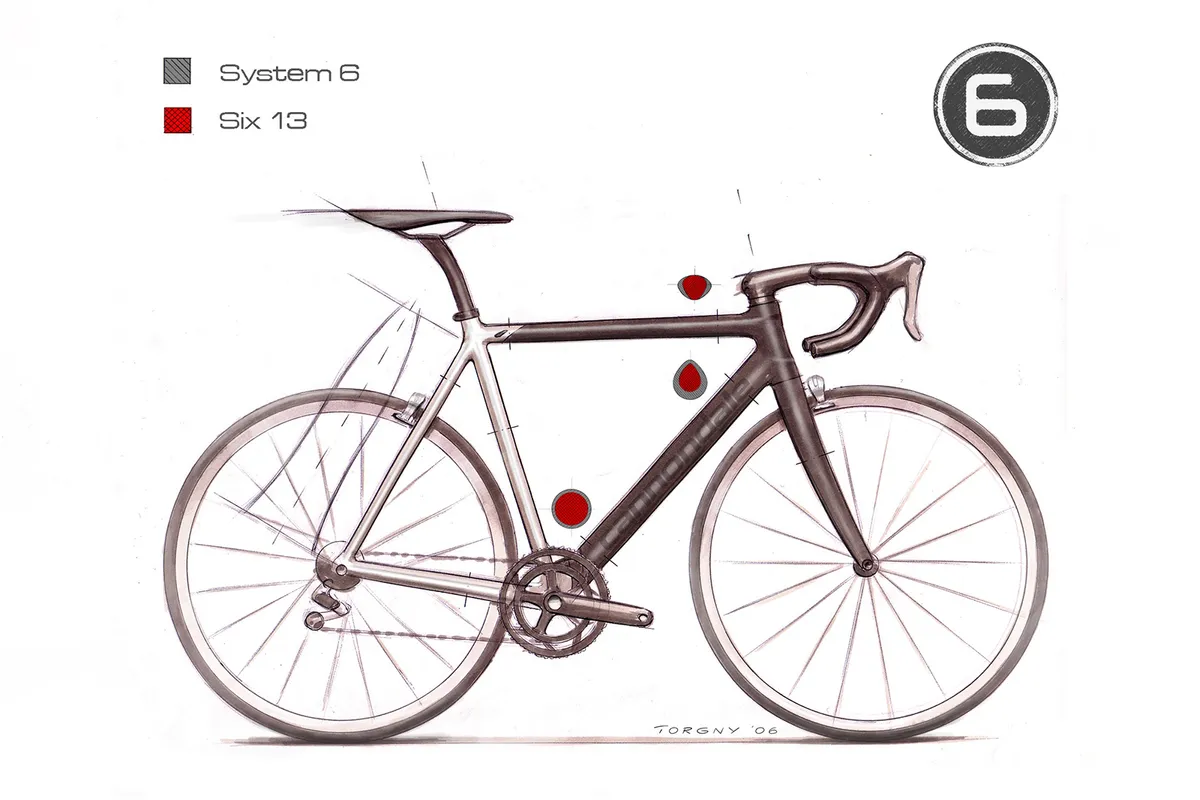

08 / Cannondale: “The original SystemSix was quite unique not only because of the manufacturing process [aluminium back-end and carbon front], but also because it was brutally stiff in torsion and had out-of-this-world power transfer, while still providing some vertical compliance due to the layup and seatstay shape. I still ride mine when I go back home to visit my parents in Norway and apart from the weight it still holds up very well with modern bikes."

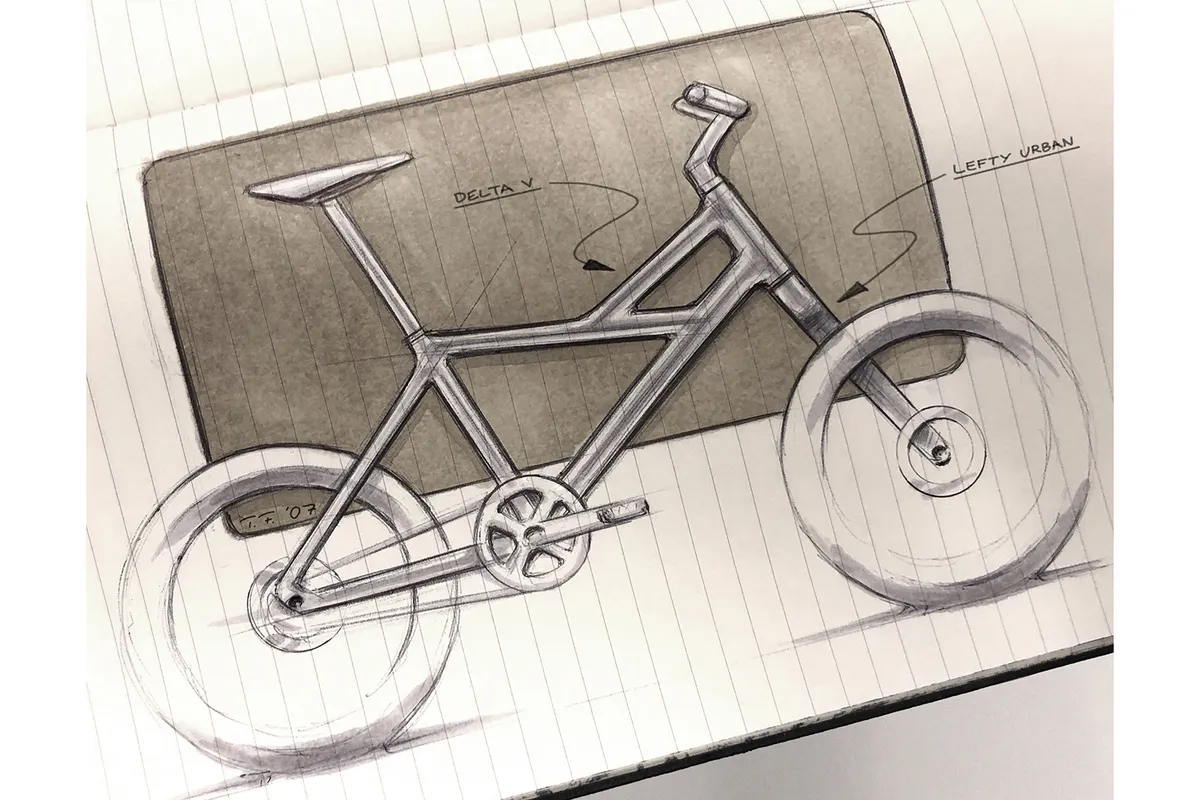

09 / Cannondale: “The Hooligan was the brainchild of Chris Dodman (Cannondale engineer behind the SiSL chainset and BB30). The idea was to do a fun, nimble and sturdy bike for young-at-heart urbanites. The slogan was ‘Ride it like you stole it’. I got to do the industrial design, which was inspired by the Delta-V frame from the early 90s, and this model stayed on the market for 12 years. Japan was the biggest market for this bike.”

BikeRadar: You’ve seen the evolution from the early days of carbon fibre and alloy hydroforming to today’s fully integrated designs. Where do you see bike design heading next?

“Well, first of all, I think cycling as a means of transport has a fantastic future. Of course, there are obvious benefits in terms of emissions, health and congestion, but in my opinion, the real magic about urban cycling is that you can turn what for many people is just a necessary evil – commuting – into one of the highlights of the day. Of course, that will require better cycling infrastructure, and it’s great to see that many countries and cities are making some good progress on this.

“Now, regarding cycling as a sport, I think we’ll see even more blurring of categories, bikes that combine a bunch of things; bikes that are light and aerodynamic and comfortable, which so far has seldom been the case. I think this is a great thing, as those who can only afford to have one bike will enjoy a wider range of ride situations through this increased versatility.

“There will also be more ebikes, as newcomers to cycling are much less keen on suffering than those who have been riding all their life. I also think, in general, digital integration will be even more common, as the next generation of cyclists are used to having some sort of digital aspect in pretty much everything they do.

“As for materials and manufacturing processes, this is one of the biggest questions for me. Everyone knows the current way of producing carbon fibre is far from sustainable, but so far nobody has come up with greener solutions that can compete in terms of weight and performance. In other words, there’s a great opportunity to be the first!

"As for longevity and trends, my hope is that we get to a situation where large bike manufacturers start picking up more of the current zeitgeist and continue to put more focus towards developing products that won’t get obsolete that fast.”

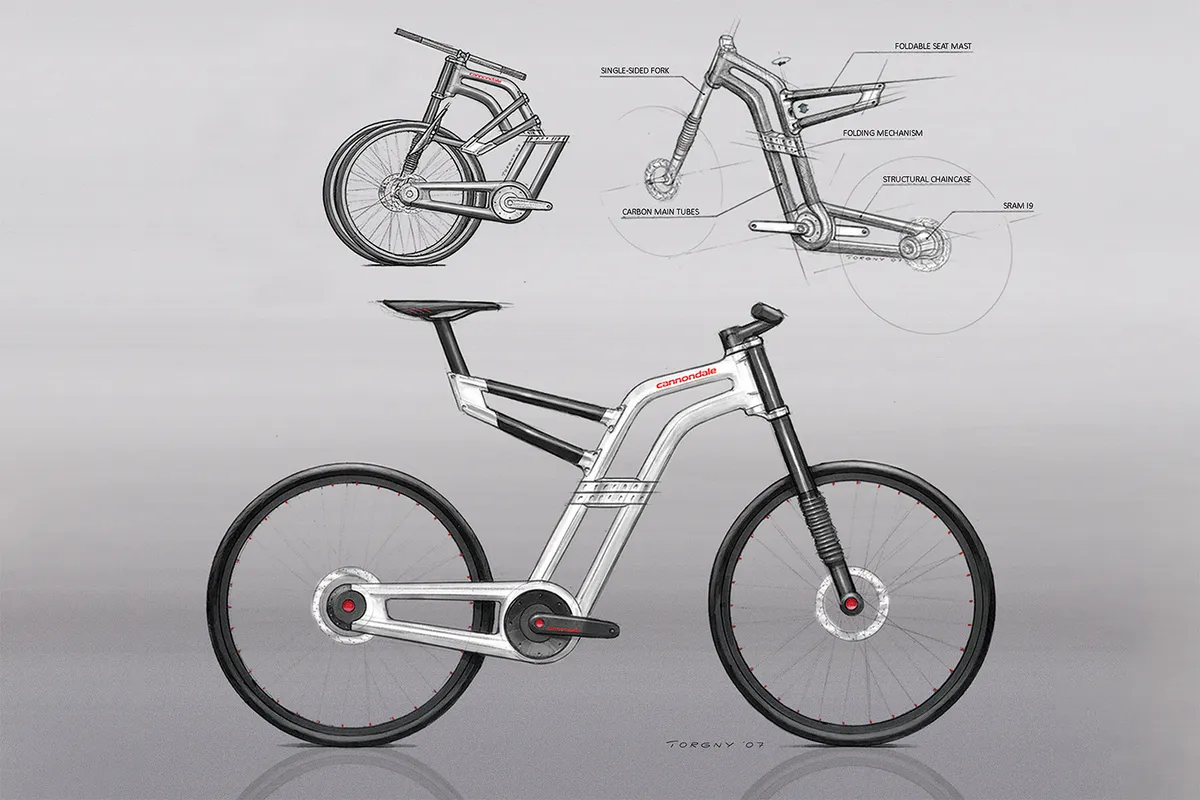

10 / Cannondale: “The On concept started out as a student project and we put a fair amount of resources into it, but never went to production, which was disappointing for us at the time, but totally understandable since it would have required a very large investment. Both the folding mechanism and the single-side chain case were patented though, and SRAM made a single-sided i9 hub gear for it. Later on, a highly diluted version of the bike went to production. The chain case was simply mounted to a regular front triangle, mainly because 500 units of those single-sided hubs had to be used. We also proposed an electric version of it, and that’s the one I feel would have had the biggest potential today.”

- Read more: Cannondale onBIKE – first look

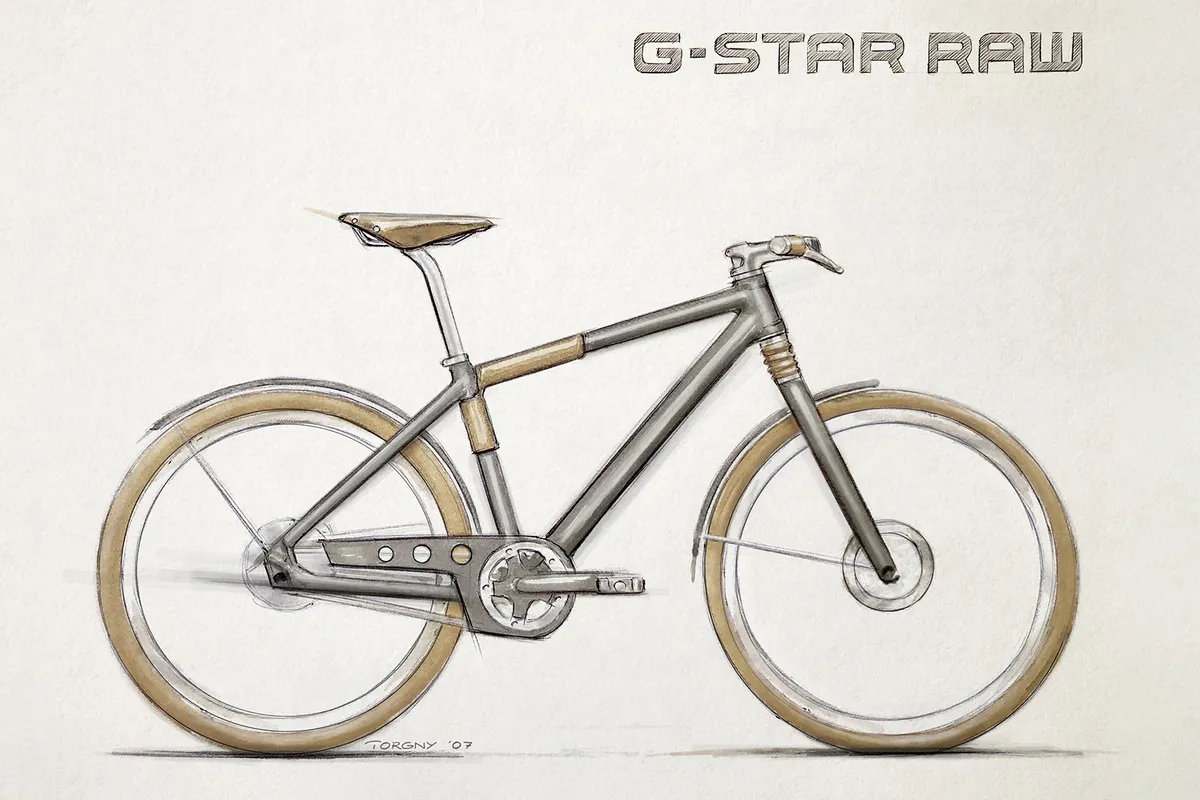

11 / Cannondale: “The G-Star collaboration helped put the Cannondale urban bikes on the map. It had an integrated light made by USE and lots of custom parts (even from Shimano!). It got a ton of coverage in lifestyle press helping us to reach people who never read cycling magazines.”

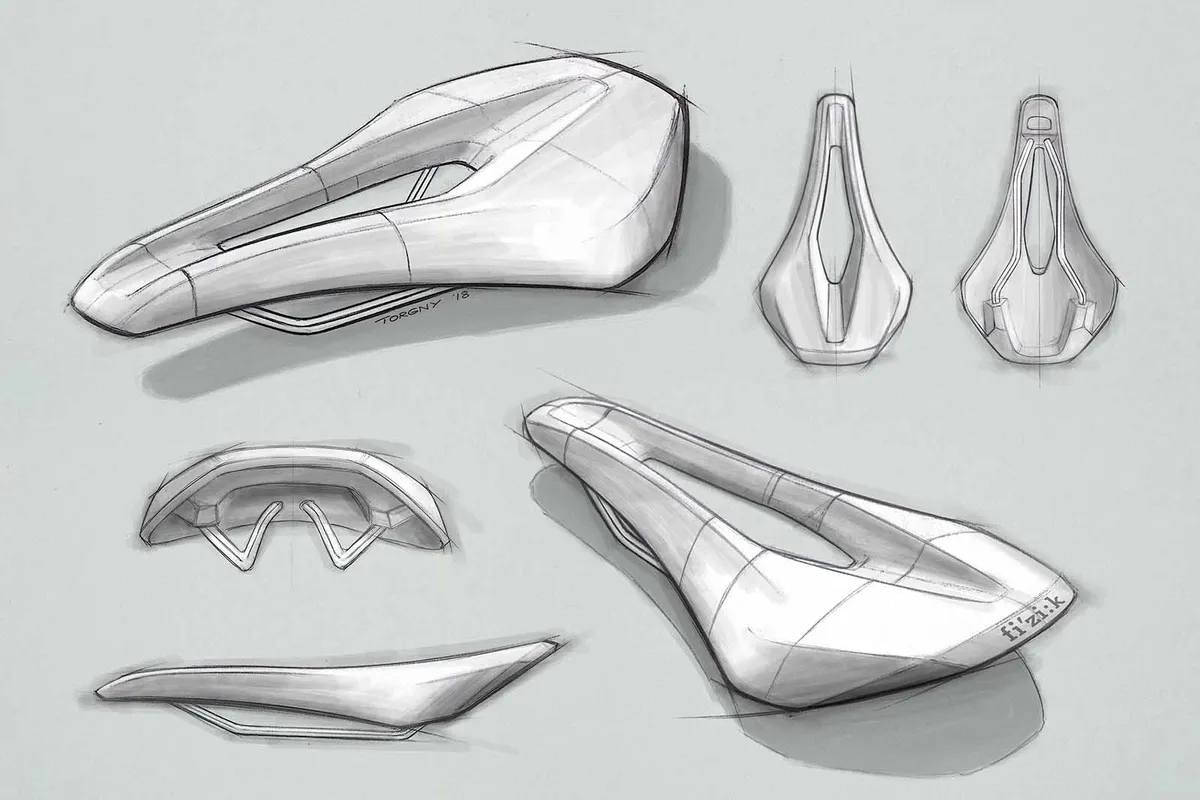

12 / Fizik: “The Argo Vento is part of a new range of short-nosed saddles from Fizik. It’s very cool to work with this company as it has some very talented and nice people and impressive facilities. On saddles, you have tons of constraints and in addition to product managers and engineers, you also have medical professionals heavily influencing the product, so collaboration is key.”

- Read more: Fizik goes short-nosed with new Argo saddles