In the west of Milan, the headquarters of Cinelli and Columbus share a compound. Since Antonio Columbo, whose father started Columbus in 1919, bought Cinelli in 1978, they’ve been part of the same family – and the same sense of artistry runs though both brands, albeit in very different ways.

From the outside, the adjacent buildings blend in with anonymous-looking warehouses, factories and other surrounding enterprises. There are no signs on the gates or walls to indicate the wealth of history, creativity and craftsmanship that lies behind them.

Cinelli: serious, yet joyful artistry

We start off in the Cinelli building, which is home to the firm's design studio and offices. As soon as we get through the door, it’s obvious this is a place designed to nurture expression and creativity. Paintings, photos and pieces of graphic design cover most of the walls – and it’s not just images of bikes.

Walking round the Cinelli offices, you're in no doubt that it’s meant to be a creative space where ideas can be developed

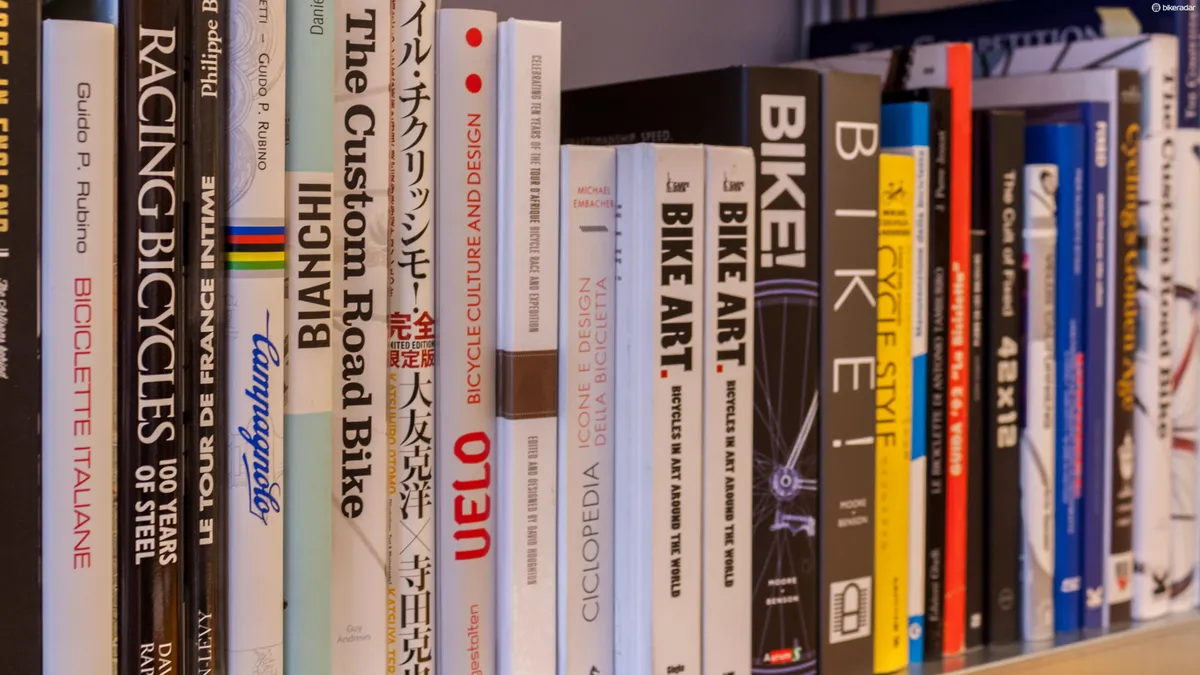

The small design studio is just off the main corridor and is, as you’d expect, one of the focal points of design in the company. It’s here that ideas are germinated: where designs for bikes, frame paint schemes, parts, clothing and everything in between get developed. Bookshelves heave with the weight of countless bicycle design books, which sit alongside magazines, journals and books covering a range of visual culture from fashion to architecture and a whole lot more.

On the one hand, a trip around the Cinelli HQ leaves you in no doubt that this is a company that takes its design very seriously, not just from an engineering standpoint but aesthetically too. The care and thought put into everything from liveries to bar tape and pin badge design is painstakingly evident.

Yet there's also an undertone of playfulness – a facet that's a crucial part of Cinelli’s identity, and something that differentiates it from so many bike companies. That seems to have a lot to do with owner Antonio Columbo, whose office we’re invited to look round.

Paintings and the iconic Keith Haring Cinelli Laser in Antonio Columbo’s office

Like the design studio next door, it celebrates cycling, art and design to full effect. And much like the design studio, one wall of the office is taken up by a floor to ceiling bookshelf, filled with volumes on bike design, art, graphic design, graffiti and photography.

But Columbo is a huge fan of art, and something of a collector. There are photos, canvases and drawings hanging on most of the available wall space – this is not your typical sober office, but a joyous space.

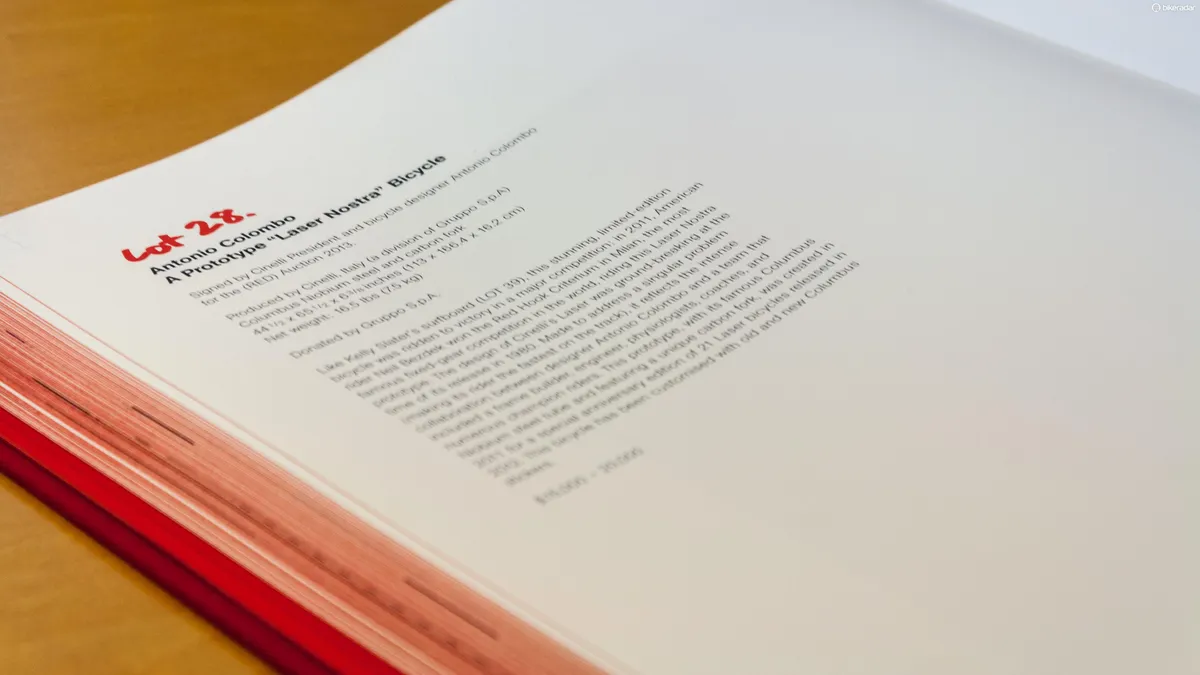

Behind Columbo's desk hangs a huge canvas drawn by the artist Keith Haring, who created the famous Keith Haring Cinelli Laser by painting his iconic figures on the bike’s disc wheels. Columbo comes across as a likeable, fun personality and when taking in his workspace, it’s clear he’s an important, driving figure when it comes to Cinelli's culture and values, so heavily bound up with creating distinctive, good looking, art-informed items.

Columbus: the noise of true craft

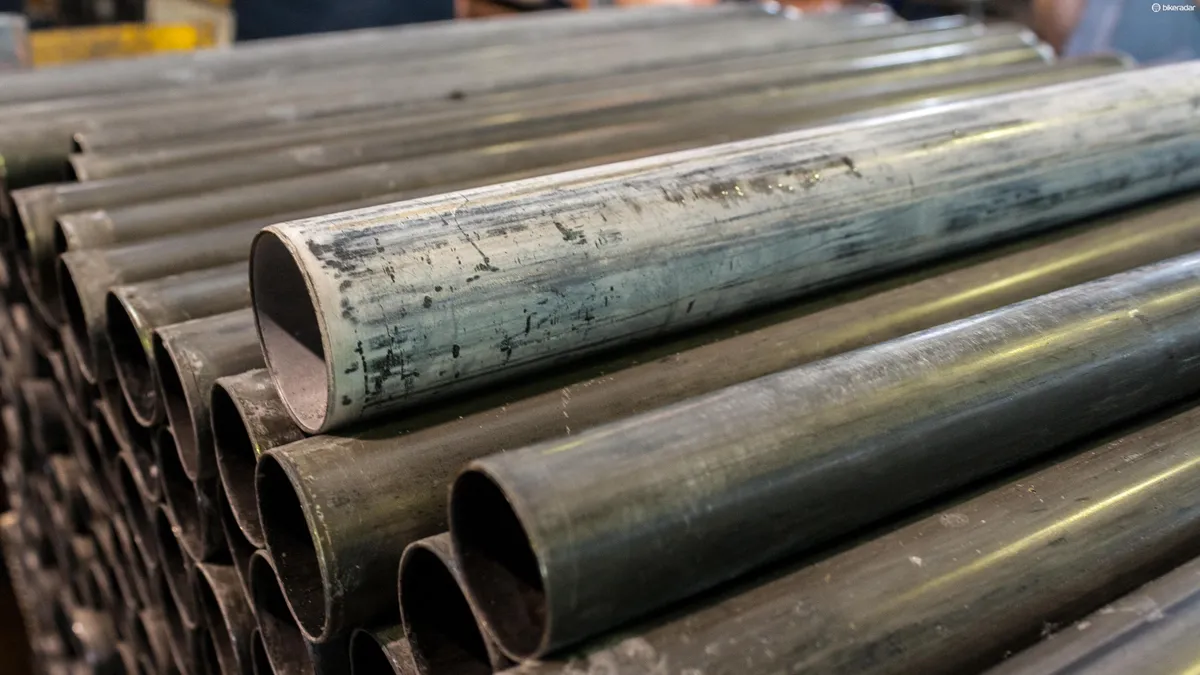

In contrast, the Columbus factory is dirty, loud and industrial – exactly what you’d expect from a facility that produces tubesets. There are, however, still visual links between it and the Cinelli building opposite – such as the huge mural on the doors and paintings dotted about the warehouse.

Street artist Z10 Ziegler has painted this figure on the entrance to the Columbus factory

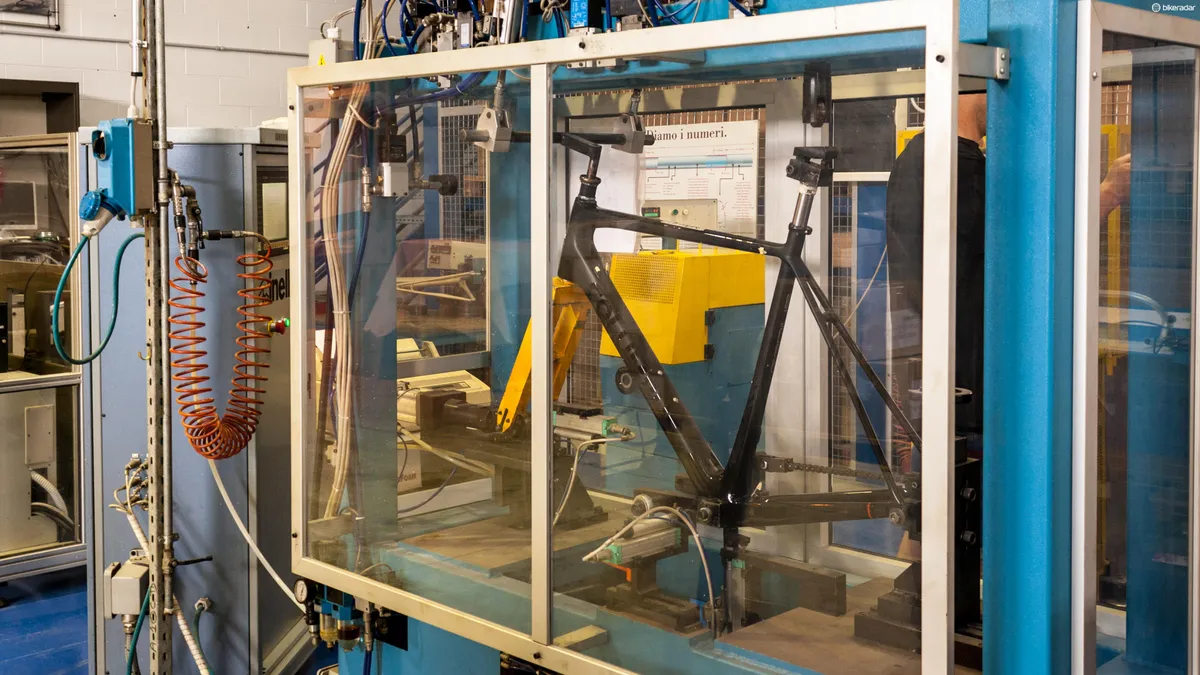

As well as being the place where Columbus tubing is produced, the factory is also where rides are painted, assembled and tested. The warehouse area is full of boxed up frames and bikes, ready to be shipped all over the world, and they sit alongside frames in various stages of production.

The factory isn’t particularly big, but it’s busy, and packed full of machinery to check, shape, stretch, bend and polish the steel tubing it’s so famous for. Creativity takes on a different flavour here than at Cinelli, yet it's certainly still evident.

Donato holds up two different grades of sanding belt, used to polish the tubes

There’s no sense of the work being a massive industrial operation. There are no conveyor belts or automated processes knocking out parts. Rather, the operatives on the shop floor work on just one or two machines, developing and honing specific skillsets and infusing the factory with an air of real craftsmanship – and justifiable pride in the work being done there.