Calling something a ‘standard’ implies that nearly everyone uses it. What we have in the bicycle world today, however, is anything but.

Instead, seemingly every company feels the need to do everything their own way, and what we’re all left with are a bunch of specific sizes, not standards. It’s a pain in the ass, and it’s high time the industry put their petty differences aside to make things easier for us, not harder.

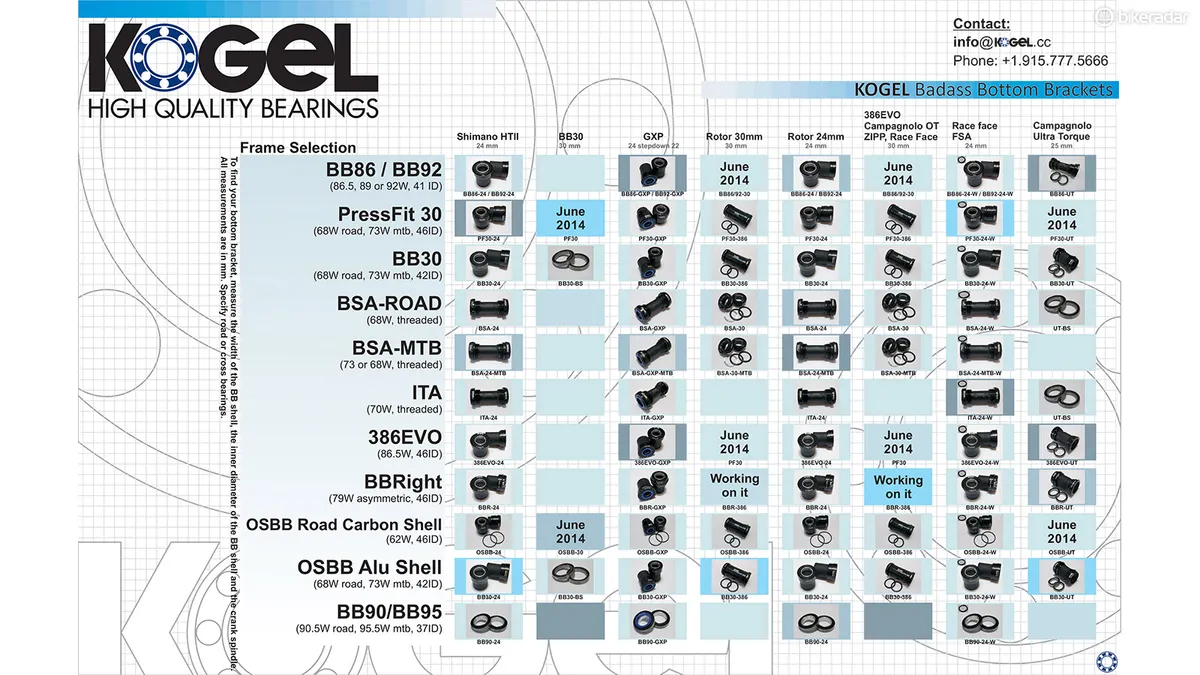

Full Speed Ahead’s complete MY2016 catalog is quite the encyclopaedia with 432 pages of the latest bits and bobbles. However, a whopping 52 of those pages are devoted solely to different types of bottom brackets. More than a few companies now offer huge posters depicting various cross-compatibilities between threaded, BB30, PF30, BB386/392EVO, PF86/92 bottom bracket shells and different crankset spindles.

Related: Complete guide to bottom brackets

As if that weren’t bad enough already, there are variants. Early Specialized OSBB shells aren’t the same as current ones, for example, and Felt’s carbon fiber BB30 shells are slightly different from metal ones. Worse yet, PF86/92 shell bore diameters can vary depending on whether companies spec Shimano or SRAM on their complete bikes.

FSA's MY2016 catalog devotes nearly a quarter of its pages to just headsets, bottom brackets, and chainrings

That same FSA catalog also includes 42 pages just for headsets, covering internal cups, external cups, mixed internal/external sets, true integrated designs, etc. If you’re looking for a headset for your bike, you not only need to know how the bearings fit in the frame but their specific internal and external diameters, and oftentimes even the angle of the cartridge taper.

Not feeling frustrated enough yet? Let’s discuss chainrings. Whereas mounting standards were once fairly standard, it’s now a free-for-all. Shimano’s asymmetrical four-arm road pattern isn’t the same as Campagnolo’s four-arm road pattern, which isn’t the same as FSA’s asymmetrical four-arm road pattern, which isn’t the same as FSA’s new asymmetrical four-arm compact mountain bike pattern, which isn’t the same as FSA’s previous three-arm compact mountain bike pattern.

A few years ago, Deda Elementi championed a four-bolt, two-arm layout. Miche has its own six-bolt interface. You get the point.

None of these things are anything like the others

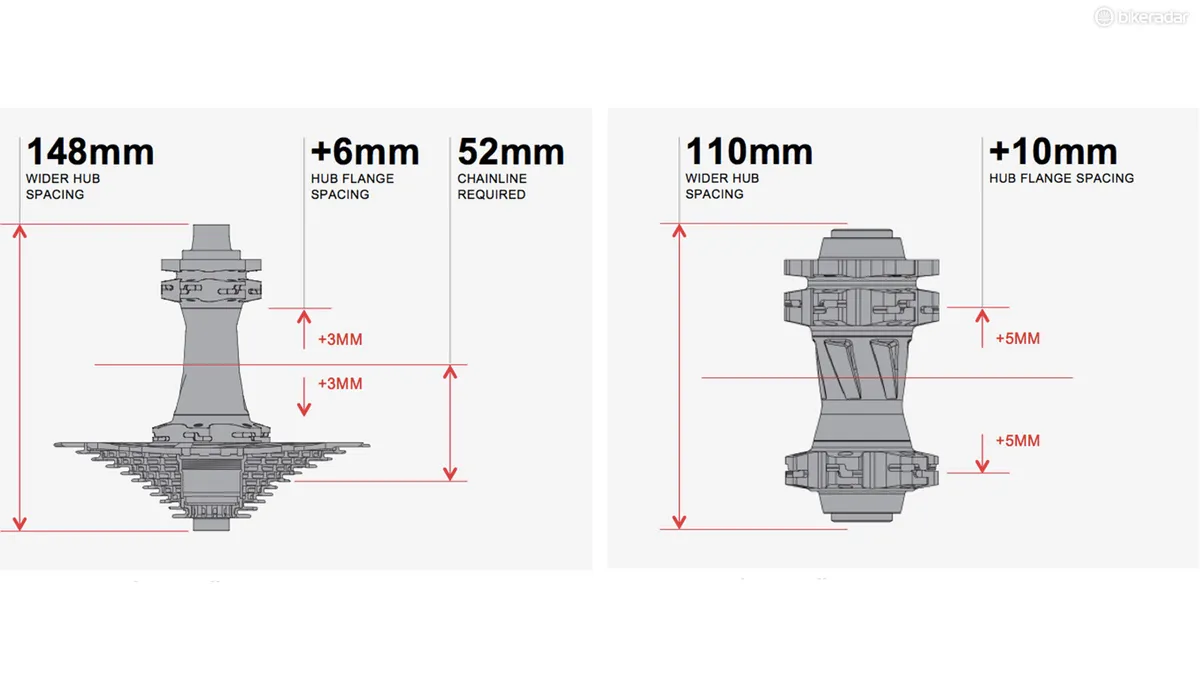

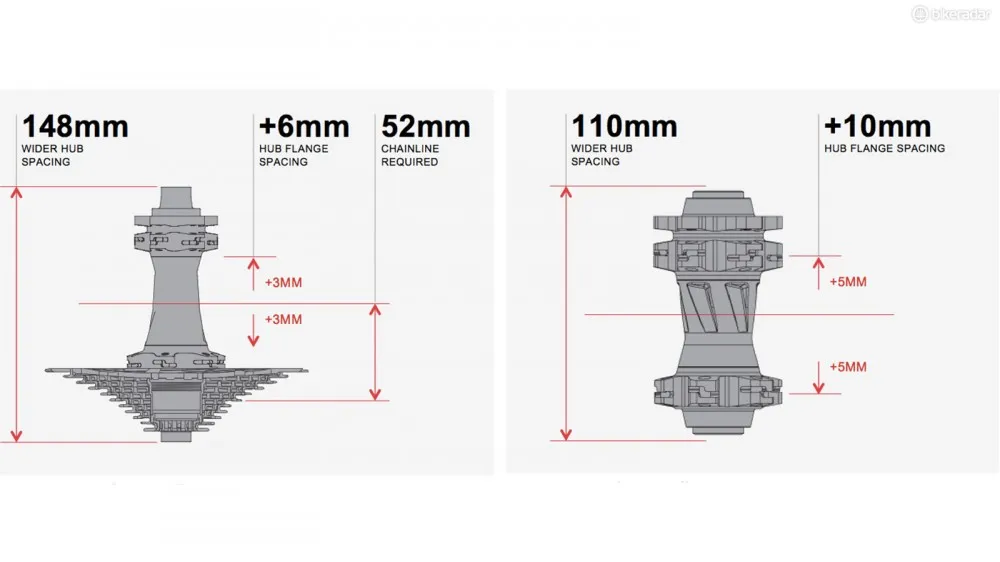

We’re rapidly heading in a similar direction with hub spacing. Just when 142x12mm rear and 100x15mm front dropout interfaces were starting to seem universally adopted (at least as far as the hubs themselves are concerned; skewers are a whole different story), we now have the wider Boost 148 and Boost 110 fitments that are suddenly about to be adopted industry-wide. And because someone deemed 100x15mm to obviously be too heavy and bulky for the road, slimmer 100x12mm options are now on the way. Marginally better-on-paper Turbo, Jumbo, Mega, Mini, Micro, KindaSortaMaybe, and ButThisOne'sGreen are sure to follow.

I fully appreciate that given such a fiercely competitive market, every company is looking for even the slightest edge to make its products seem more appealing. But do such tiny differences on paper really make any difference in the real world? And what practical sacrifices are we making to produce these increasingly marginal gains?

Finally assembled a stable of awesome trail bike wheels? So-called 'Boost' spacing is about to render all of them obsolete

Sure, I’d argue that top-tier racers who genuinely need every iota of advantage they can get might benefit from seemingly inconsequential differences. Half a watt here and a quarter of a watt there can – and do – add up. But the rest of us are far more concerned with whether we’ll be able to find a replacement chainring in five years or the right spoke length at our local shop. And no one wants to hear that their bike’s unique headset bearing will have to be specially ordered from Germany and won’t arrive for three weeks.

It’s true that automotive companies regularly use parts that are truly make, model or year-specific with virtually no cross-compatibility. But while there are laws guaranteeing that replacement parts will be available for a certain number of years, no such rules apply in cycling. And as much as companies try to use ultimate performance (at any cost) as a means to get people to buy bikes, the reality is that one of the most entertaining aspects of our sport is the ability to tweak, modify, and customise our machines at will.

If anything, I’d argue that the growing adoption of new and increasingly specific ‘standards’ stifles that flexibility, resulting in riders buying less stuff, not more. And, if and when those specific ‘standards’ turn out to not work very well, we don’t blame that ‘standard’ – we blame the company that decided to use it.

What would be nice is some sort of industry consolidation where companies can put aside some of its pettiness and instead strive to make lives easier for the rest of us. Winning test numbers from a fancy frame stiffness jig are nice and all but there’s also a tipping point for when some sort of technical ‘innovation’ isn’t worth whatever other sacrifice has to be made to get it.

There’s no test for practicality but that doesn’t mean it doesn’t also have value.

I’ve got a box of headsets that won’t fit in anything. I have a drawer full of bottom bracket spacers, wave springs, and washers that I hate using. And pretty soon, I’ll have a bunch of beautiful wheels that will all be instantaneously obsolete.

I love technical innovation as much as anyone – and not surprisingly, I embrace it more than most. But that said, there have to at least be some considerations made when it comes to the people who are actually buying the stuff companies are developing.

Can’t we all just get along, maybe at least just a little bit?