Jeff Steber, owner of Intense Cycles, not only created the first full-suspension downhill-specific bike, but also set the benchmark for excellence in gravity design every step of the way.

Before Jeff got interested in building bikes, World Cup downhilling was being done on hardtails. Who knows where we’d be right now if he hadn’t welded his first full sus bike on his patio in Lake Elsinore, California.

Jeff used the knowledge gained from designing, prototyping and testing hang gliders to build his first bike, the 3in-travel Spyder. He originally marketed it as a cross-country bike, but cross-country racers dismissed it, saying it had “too much travel”. Jeff took the bike to the Interbike tradeshow in 1993, where it caught the attention of the downhill crowd.

The show was a success and Jeff was able to focus full-time on his vision for a full-suspension, purpose-built downhill bike. A big part of that process was teaming up with BMX and motocross legend Mike Metzger and pro snowboarder Shaun Palmer. Metzger and Palmer were interested in the new sport of downhill mountain biking, but there was no bike on the market that they could use for the job.

An early prototype of the M1, circa 1999. The heavy moto styling has been handed down to current Intense race bikes

Jeff knew that if he was going to make a real downhill bike for gravity experts, he would have to use a coil shock for the rear suspension. No bike manufacturer was making anything close, so Jeff used an air shock from a custom truck suspension company.

Then something amazing happened. Shaun Palmer won the 1996 US Nationals on a linkage-driven, 6in-travel Intense M1. “All of a sudden, all the parts that I’d been dreaming of to make a better downhill bike with started flowing in,” Jeff reminisces. The rest, as they say is history.

Palmer went on to sign a major deal with Specialized, but the evolution of the M1 continued on without him. The technology that Jeff had developed was so far ahead of the ‘big’ companies, that many major bike brands bought M1s and rebranded them with their logos. In fact, Greg Minnaar won his only World Championship on a Haro-badged M1.

Shaun Palmer's iconic M1 was the bike that put Intense Cycles on the map

The ingenuity and hands-on approach that led to the great success of the M1 is still alive and well today. All of Intense’s full-sus frames are still hand-welded at the factory in Temecula, California. Jeff has his own private lab, where he can tinker with new ideas and bring them to life.

The creative freedom Jeff has is what sets Intense Cycles apart from other bike manufacturers. While most companies have to wait for their prototypes to be built overseas, Jeff can instantly turn his ideas into reality. This leads to the creation of some of the most cutting-edge bikes on the planet.

BikeRadar: Intense Cycles have a rich history of racing. What did the guys from your original Factory Team, such as Shaun Palmer, do for the sport?

Jeff Steber: It was perfect timing when Intense hooked up with Palmer. At that time, downhill racers wore Lycra skinsuits and rode hardtails. Palmer brought the moto influence to mountain biking with his cut-off moto pants and aggressive in-your-face attitude. His all-or-nothing style of riding changed the face of downhill. We put our notch in the history of mountain biking in the mid to late 90s and built the Intense image back then.

You were basically a one-man operation then. How did you manage to develop these groundbreaking designs while the big companies lagged behind?

I was the little guy out there in the trenches listening to what the racers told me. I was at all the races and had a strong relationship with my riders. They told me what they wanted and we made it. I’ve always been very hands-on with the design process.

How has this approach given you an advantage over companies who don’t do their own manufacturing?

We do all our own manufacturing in-house, I have a really quick turn around from having an idea to being able to ride a prototype. I can fabricate a bike in the morning, weld it, heat- treat it and build it up the next day.

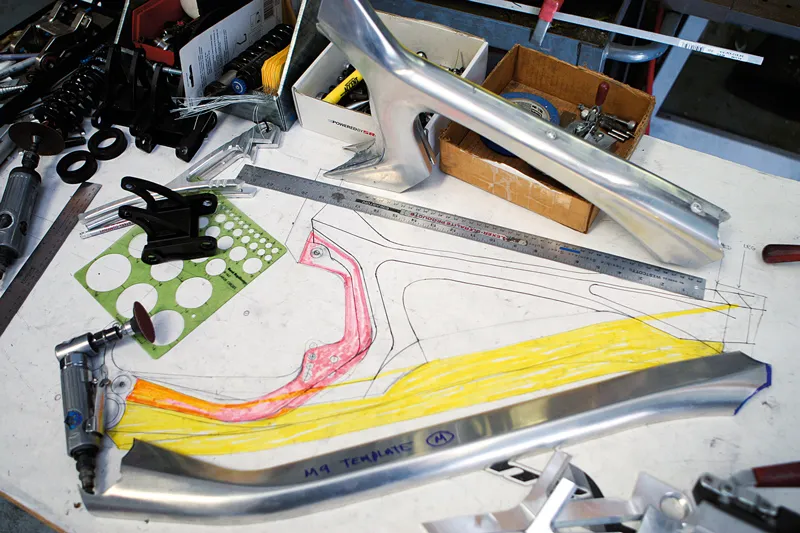

All new bikes are still designed in-house at Intense

Most US bike companies don’t do their own manufacturing anymore because it’s cheaper to have it done in Asia. How are you able to still make your bikes in America?

By controlling our manufacturing, we can react to changes in the market and create trends where we see a need. We have a very lean manufacturing setup, similar to the Toyota style. The idea is to keep a tight inventory of parts, so that you don’t get stuck with a bunch of models that people don’t want. We can make niche models that people want right away. Bike companies who have their bikes made in Asia have to plan out their production much further in advance and can’t react as quickly as we can.

Will you always manufacture your bikes in the USA?

Definitely. Other US made bikes cost hundreds of dollars more than ours. Because our frames are made in house, we’re able to provide a great value to our customers. We cut out the middleman and are able to pass that saving along to the consumer. Even if someday we have some mid-level bikes produced in Asia, this factory will never go away. For my creative process to work I need to be able to hold the materials in my hands and create. It’s like if I were a clothing manufacturer and didn’t have a sewing machine or didn’t know how to sew.

Tell us about the process of creating a new bike. How do you come up with your ideas?

Just like in the early days, I listen to the riders. We look at what people want and try to be very responsive. I always start a new bike with a piece of an older model. The same DNA as the original M1 is in every bike we produce.

Jeff’s workbench has produced some of the greatest downhill bikes ever

The last few models you’ve made have one thing in common – they are all highly adjustable. Why is this?

People don’t have the money for three high-end bikes anymore, so we’ve incorporated features in the new Uzzi, Tracer and 951 that allow you to change the whole personality of the bike. By being able to quickly change the geometry and travel, the bike can evolve as your riding style changes. For example, if you’re going to Whistler, you can put on a different fork and wheelset and your bike takes on a whole new personality.

Intense have always set trends, but you have no carbon fibre bikes in your line-up. Will this change soon?

Over the next two years you’ll see three carbon fibre models from us. Great advances have been made in the manufacturing of carbon bikes over the last few years. We’ve held back and let the bigger companies lay the groundwork. The facilities that they’ve created can make some really good products now. At first we'll have to produce our carbon bikes in Asia, because they're more technically advanced in that area. We plan on having the front and rear triangles of the carbon models fabricated there, but the linkage, machine parts and assembly will still be done in the US.

We're in the process now of organising a carbon fibre prototyping facility here in California to allow us to do prototypes and small quantity runs. It would help us learn the proprietary process ourselves too. That could evolve into manufacturing carbon fibre bikes here. If Intense are going to make a carbon bike, we need to use a state-of-the-art process. I’m not going to pick a mould out of a catalogue in Taiwan and put an Intense badge on it. I have to have a hand in it from the start, or it’s just not an Intense.

Frames freshly back from painting get a moment to breathe before assembly and shipping

Intense's downhill racing timeline

- 1981: Jeff discovers mountain biking after being heavily into motocross and hang gliding.

- 1993: Jeff builds his first frame, the Spyder, a 3in-travel full-suspension bike, on his patio in Lake Elsinore, California.

- 1994: Jeff unveils the M1. The Horst link design and 5in of rear travel revolutionises the world of downhill racing.

- 1996: Intense's first factory team is formed. Shaun Palmer, Randy Lawrence and Mike Metzger go on to become the godfathers of modern downhilling.

- 1996-2000: The M1 is refined further and many other bike companies rebrand the frame for their race teams. Gee Atherton (Muddy Fox), Greg Minnaar (Haro), John Tomac (Giant), Brian Lopes and Eric Carter (Mongoose) all rode Steber's steeds to victory.

- 2002: Intense partner with Santa Cruz to license the Virtual Pivot Point suspension system patent. This system improved pedalling efficiency as well as giving a better small and large bump feel.

- 2004: The M3 replaces the M1 and uses the new VPP suspension system. The M3 was the first Intense bike to have 9.5in of rear travel.

- 2006: The M6 comes on the scene to replace the M3. The M6 uses a more refined version of the original VPP system.

- 2008: Intense introduce the lightweight Socom FRO for racing on courses that don't require as much travel as the M6. With 8.5in of rear travel, the Socom was the weapon of choice for courses like the Sea Otter Classic.

- 2009: Understanding that World Cup tracks vary greatly, Jeff created the highly adjustable 951. By changing the travel setting and dropout position, the 951 can be suited to any course.

- 2010: Prototype M9 bikes were ridden by the Chain Reaction Cycles team on the World Cup circuit.

Team riders Chris Kovarik and Claire Buchar with a prototype M9 frame