Technology is infiltrating cycling at every level and nowhere else is this as true as in performance tracking. Barely a day goes by where we don’t receive details about some flashy new smart trainer, power meter or GPS in our inboxes.

Road cycling techies and academics the world over are developing increasingly advanced systems in the hope of being able to better predict and track the performance of athletes.

One such study is being carried out by Alice Bullas, a PHD student at Sheffield Hallam University, and the really exciting thing is that the tech she uses could soon be coming to your smartphone or tablet.

Alice is studying how body scanning can be used to predict athlete performance and invited our resident racing and video extraordinaires, Joe Norledge and Reuben Bakker-Dyos to check out the groundbreaking kit.

Can body scanning predict an athlete's performance? Joe and Reuben travel to Sheffield Hallam University to find out

Why is body scanning important?

Until now, quantifying improvements through training has been a relatively inexact science.

Though the use of power meters, the traditional method of measuring changes in the circumference of a cyclist’ thighs and simply timing efforts, gives us an insight into what’s going on in an athlete's body, they don’t give us the whole picture.

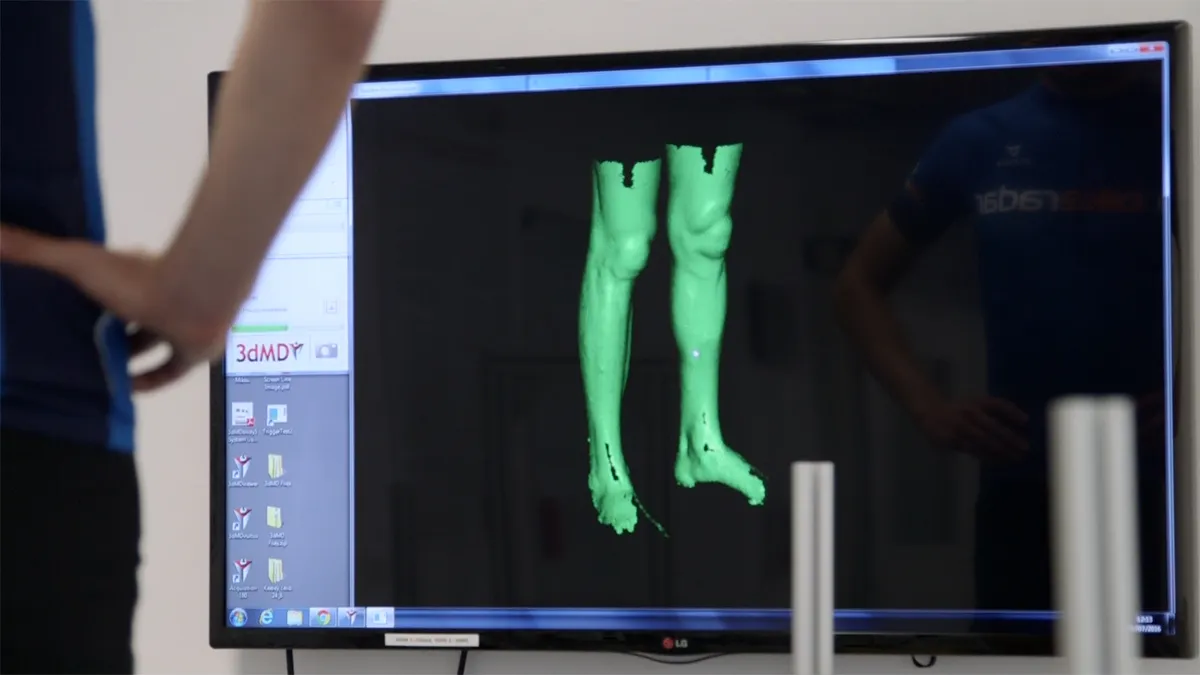

Compared to the aforementioned methods, body scanning uses a bank of cameras — £80,000 worth of kit in this case — to create a highly detailed 3D model of a rider's legs. Once this model has been created, the system essentially computes the volume of a rider's legs and tracks any changes to this over time in extremely high detail.

Unsurprisingly, compared to the old method this gives a much more accurate picture as to what changes may be occurring in an athlete's body.

The system also makes use of a full body composition analysis to gain a more complete picture of an athlete's build, measuring things such as body fat percentage, water content and any imbalances of leg muscles.

Quantifying change

So how can this data be used?

In one case study, a rider was tracked over eight months of training and when assessed using traditional methods, his legs showed a mere 0.5% of growth compared to the 2.5% that the body scanner showed.

Although most would be happy to discover they were a little stronger than they’d initially thought, this is a hugely valuable insight which means riders could shape their training more effectively.

In this scenario, the rider may have been able to determine that they’d reached their goals earlier than expected, meaning that they could cut back on their training regime, reducing the risk of overcooking themselves in the run up to a season.

Although this sort of data will undoubtedly be useful for athletes and coaches, it is also expected that the technology could be utilised in talent-scouting, where coaches could quickly determine what field of cycling a candidate is best suited.

The results

In our test, the body scanner was used to predict the performance of Joe and Reuben on a stationary bike equipped with a power meter.

Common wisdom dictates that their respective builds — Joe being alarmingly skinny and Reuben a muscular, watt producing powerhouse — would be reflected in their power output and the body scanners predictions correlated with the real world results, with Reuben producing 1,889 watts and Joe 1,527 watts.

While the performance data didn’t tell us anything we didn’t know already, the body scanner’s ability to predict performance is undoubtedly impressive.

Interestingly, Reuben’s muscular balance was very even with only a 2% discrepancy between his legs whereas as Joe wasn’t quite as balanced, with a 9% difference between his, likely down to deterioration caused by old injuries.

This data could be used to help produce effective recovery and training regimes for Joe or other athletes following an injury.

The future

We’re sure that most of you will be asking why this is important, particularly given that you’ll need a cool £80k and a specialist laboratory to get started with your very own body scanning kit.

Well fret not as the technology may be coming to an app store near you! As part of Alison’s work she’s developing methods which would allow the technology to scale down to the point where it could be adapted to work in a tablet or smartphone.

We have no doubt that the majority of people will continue to be content tracking their training on feel alone, but for a dedicated few amateur racers, coaches and professional riders, this looks set to be an invaluable bit of tech which will bring a little bit of science to the dark art that is human performance.