Despite his 6ft-plus height, I’m struggling to keep my fellow rider and guide in my sights. And as the sun sets, anxiety about being left behind on a hillside that’s renowned lion territory starts to gnaw at me.

I’d been warned about riding with Tom Ritchey by various industry types, but my idea of an interview involves throwing a leg over a bike for an hour or two; how else can you get under the skin of a rider? Right now, as I gasp for breath along miles upon mile of flowing singletrack, I’d almost prefer it if he was just another overweight executive.

“Overweight” and “executive” are not words you would use to describe Tom, though. Even as CEO of Ritchey Design, the long-running component company he started in ’83, Tom needs little excuse to ride; perhaps the reason he so readily accepted my interview request.

Considering he clocks up some 10,000 miles in the saddle each year, it’s hard to believe he has any time for his CEO and company president duties. “I have a great executive team that covers for me a lot,” he says with only a hint of guilt, before adding, “My job has been reduced to product development.”

I’m about to suggest that overseeing product development at a company whose components are seen on spec sheets worldwide is hardly a reduced role when he sees that he’s perhaps played down things down too much and interjects with: “All product is my responsibility. That’s what I do: I’m Mr Product.”

Product, or rather product quality, is in Tom’s blood. Back in the early 1970s, when he was racing road bikes at national level, he was designing and milling his own components, trying to get an edge over his rivals. He’d bought a lathe and a milling machine at 16 and set about making his own hubs, bottom bracket shells and seat posts.

When asked whether this creativity was down to a deep-seated passion for engineering (his father was an engineer), he retorts, “Heck, no, I was self-centred to the core. I was a racer, I wanted to go faster than my competitors and I needed to make my bike lighter, stronger, tougher and better.”

It’s this “stronger, tougher, better” ethos that Tom strives for throughout the Ritchey line today: a range that includes seatposts, headsets, pedals, saddles, bars, wheelsets and more.

Of course, product testing for Tom means just that, and as we soar down the dusty trails near his rambling home in the hills south of San Francisco, I’m aware he’s responsible for a lot of the development that has produced today’s mountain bikes.

Those who discovered mountain biking in the early ’80s (like me) cut their teeth saving up for Ritchey Logic cantilever brakes and buttery smooth headsets to adorn cross-country rigs, idolising both the simplicity of their design and the fact that they worked so well.

“Classic, race-tough and trusted. It’s still the same,” he says of current components, “but Ritchey represents value too. To me, I’m the guy who’s out there buying stuff in the store and I don’t want to overspend just because it has the Tom Ritchey name on it!”

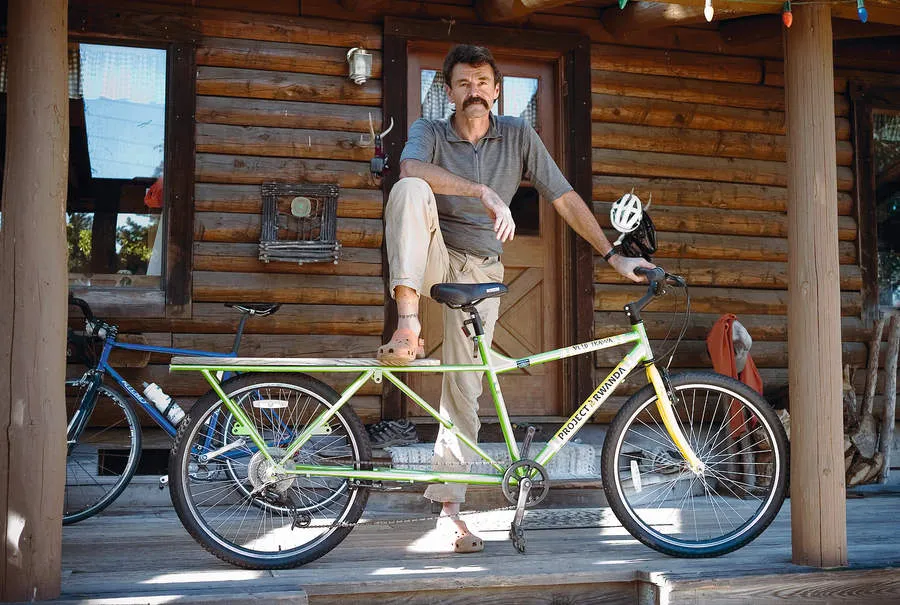

Indeed, everything about Tom’s daily existence seems to be very down to earth, and when I first rolled up at the wooden cabin that’s been his family home for decades, I found Tom busy in his workshop.

A quick look around revealed half a dozen metalworking machines and a welding jig – the latter holding the barely finished skeleton of a tandem bike with welds so smooth that it could almost be mistaken for a monocoque construction.

It’s this frame-building prowess that created an initial splash for Ritchey in the world of mountain biking, when he turned his welder-wielding hands towards meeting demands for the then-revolutionary mountain bike in late 1978, teaming up with Gary Fisher and Charlie Kelly to provide the frames for their company, Mountain Bikes.

Having competed in (and won) the legendary Repack clunker race down Mount Tam, Tom’s awareness of the need for better componentry was brought to the fore when he hit a bump halfway down the course and had to pull up to rotate the bars on his own bike.

“That’s all it took. I knew I needed to make a one-piece [bar and stem] that would never slip. It’s those kind of experiences that have foreshadowed all my designs,” he reveals. What, not Marin?

Sitting on Tom’s deck, we look across to the San Francisco Bay area and the widely believed birthplace of mountain biking. “I don’t think Marin was ground zero,” Tom announces. “I’m not saying that California and that weren’t part of the history, but a bigger piece was Greg Lemond. Nobody ties Greg into any of it, but he was a catalyst. He suddenly put himself out there as an innovator: the time trial, the aero position, he re-wrote the book on rider salary and contracts.

“Back then, everything was Europe-based; there was no Japan. Peugeot, Gitane, Motobecane – they were the Trek, Specialized and Cannondale of Europe. They sponsored the big teams of Europe and it [mountain biking] went over their heads.

"They didn’t know until too late how the influence of Lemond and US-born inventiveness had happened. I feel his success was a catalyst and a lubrication that we took advantage of in legitimising what we were doing. It’s taken me a while to come to that place.”

However the mountain bike came about, Tom remained immersed in the scene when he split from Fisher and Kelly in ’83, starting Ritchey Design. “Basically, it was about understanding the bike more deeply than just the frame; it was a system of components and I was uniquely gifted when it came to design and building and machining,” he recalls.

As he speaks, I scan the line-up of bikes propped against the walls. Among the beautifully crafted frames is a brightly painted cargo bike emblazoned with the words “Coffee Bike”. While it’s not born of the Ritchey jig, it’s just as much a Ritchey creation as any other, and its existence represents a big change in Tom’s life.

It all began seven years ago, when his first wife left him. Tom found himself battling his demons: being self-centred and insecure. “To tell you the truth, people put me on a pedestal but, in a personal way, I didn’t feel good about myself, and didn’t understand it.

"I was hard on myself; when a wife leaves you they say you can go bitter or better, and I didn’t want to become a bitter person. I had good people in my life that believed in me more than I did in myself,” he says with watery eyes.

Then, in 2005, Tom was asked to accompany a friend on a bike trip to Africa. In Rwanda, a country that had experienced unfathomable bloodshed during the civil war of 1994, things were put into perspective. The seeds of Project Rwanda were sown. A year later, Tom returned to put on the Wooden Bike Classic event, lining up American riders alongside locals on homemade wooden bikes.

“Bikes are famously popular, of course, but only one in 100 people has one. Most people know how to ride a bike and, as a tourist on a bike, they just wanna race you. It doesn’t matter if they’re on a beaten, broken bike that has 100lbs of potatoes on the back of it…”

The Wooden Bike Classic, now an annual event, was just one of Tom’s ambitions. It set out to create community in, and awareness of, Rwanda. Soon a national cycling team was assembled, with Tom’s friend Jock Boyer at the helm.

“They [the Rwandan government] saw what we were doing under the umbrella of Rwanda’s national cycling team. They looked at the opportunities in cycling and saw that it is an opportunity to show a positive Rwanda to the world.”

But before all this, surrounded by ageing, rickety, rod-braked bikes that provided limited benefit on Rwanda’s hills, Tom recognised that things could be different. A meeting with Dr Tim Schilling, who headed a program to improve coffee quality in Rwanda, provided the impetus for Tom to design a bike that could truly help a coffee grower’s lot.

It would cut the time it took the farmer to transport the beans to the washing plant – key for the taste, and thus the money the coffee attracts. In the Coffee Bike’s development, Tom draws parallels to the first mountain bike’s advent.

“All it took was someone to put it together, to take the cobbled-together bikes that were already in existence, and say: ’There is a more elegant way of doing this.’ I come along in those environments and find that I’m in the right place at the right time.”

While Tom’s role in the Coffee Bike is undisputable, there are no Ritchey components on it, and you’ll have to search hard to find his name on Project Rwanda’s website. “I didn’t want people to see me being a do-gooder and making a marketing statement out of it,” he says.

It’s clear that his involvement in Project Rwanda has had a big impact on Tom, but he’s not done yet: “The most rewarding thing for me would be to have created a project that’s self sustaining… To absolve me!” he states, underpinning his criticism of typical ’handout’ philosophies (the Coffee Bikes are bought on micro-finance loans by the farmers).

“My next goal is to have an organisation: Bike Designers Without Borders. It would be about your skill as a designer – whether you’re working on $10,000 carbon bikes or basic Walmart bikes, you know something and have something to give as a servant to the third world… There are 1,000 Tom Ritcheys in the bike industry who just need an organisation to channel through.”

“The Rwandans look at a bike that’s been there for 100 years and they don’t see a lot of hope. They look at the bike I designed and they’re excited about that,” he adds, becoming agitated again, before fixing me with a steely eyed look.

“The bike needs to be a tool of excitement and fantasy, to take them to another place in their minds about their opportunities. Who knows where that will lead?” And that’s an apt question with Tom riding alongside them.

About Project Rwanda

A charity formed in 2006, Project Rwanda seeks to further the economic development of this central African nation through initiatives based on the bike as a tool – and a symbol of hope. As well as supplying Coffee Bikes to farmers and similar cargo bikes to health workers, the project aids Rwandan development by garnering media attention through the annual Wooden Bike event, the advent and training of a national cycling team, and by promoting eco-tourism in the mountainous country. Visit www.projectrwanda.org for more information and to see how you can help the project out.

Tom Ritchey timeline

- 1956: Tom Ritchey is born in California.

- 1973: Tom is road racing at the national level, machining his own components, and has welded more than 1,000 road frames by the time he leaves high school. Road racing is banned in California for one year. Tom and friends turn to riding their road bikes on the buff singletrack around Saratoga Pass.

- Mid 1970s: Unusually, Tom decides to adopt lugless frame construction. In bucking a trend, he’s free to vary geometries that different tubesets and angles offer, and surges ahead in frame design as a result.

- 1978: Tom sees Joe Breeze’s first mountain bike. Gary Fisher asks Tom to make a mountain bike for him.

- 1979: Tom works with Gary Fisher, providing 160 hand-built frames for his company, Mountain Bikes. The complete bike sells for around $1,300.

- 1983: Mountain Bikes is dissolved and sold to Fisher. Tom sets up Ritchey Design, focusing on component design and build just as he’s been doing for the past 10 years. He continues to weld frames, though, including the iconic Ritchey Annapurna.

- Late 1990s: Apart from his role at Ritchey Design, Tom continues to produce more than 500 hand-built frames per year.

- Early 2000s: A tough time: Tom’s first wife leaves him.

- 2005: Tom visits Rwanda on a mountain bike trip in Africa. What he sees has a powerful impact.

- 2006: The first Wooden Bike Classic race is held in Rwanda; 3000 spectators turn out to watch it.

- 2007: The Coffee Bike arrives in Rwanda, being purchased by the farmers through three-year micro-loans that are paid back by the 30-40 percent increase in income the bike affords.

- 2009: Tom re-marries. He has already crafted a tandem frame for his second wife and himself.