Cycling in traffic can be fun, tricky, dangerous and rewarding. According to recent data, says Matthew Barbour, it could also be damaging our health.

Bad air days

Several times a week for the best part of a decade, I could have been unwittingly but systematically poisoning myself. While I thought my daily cycle to the gym through the centre of Bristol was an efficient and harmless way to clock up a sizeable chunk of my cardio quota on top of my longer rides outside the city’s walls, my lungs and heart could have a different take on it.

Here’s what I didn’t know: with every deep draught of oxygen, I also gulp down alarming quantities of ozone, carbon monoxide, microscopic particulate matter – PM10s – sulphur dioxide, nitrogen dioxide and a witch’s brew of other pollutants. By commuting through the congested streets of Bristol, I’m reducing my lung function, constricting my air passages, courting chest pain, increasing my chances of developing asthma, unleashing free radicals to catalyse carcinogens in my bloodstream, and activating cellular processes that might at some point lead to a heart attack.

“In the 1950s in London we endured thick pea-soupers which would give you chronic bronchitis,” says Dr John Moore-Gillon, president of the British Lung Foundation and a lung specialist working at St Bartholomew’s Hospital in the City of London. “Pollution in the 21st century is invisible but just as dangerous. When I see people cycling or running along the Embankment in the middle of the day, I want to tackle them and scream at them to stop.”

While emission controls have dramatically reduced the chances of us ever experiencing the same conditions as the ’50s, with more of us driving more cars and flying off for ‘mini-breaks’, the problem hasn’t disappeared. Latest data from the Commons Environment Audit Committee warns that up to 50,000 people each year are meeting a premature death in the UK thanks to air pollution, with an annual health care bill of up to £20.2 billion. The biggest culprit? Transport, responsible for 70 percent of pollution in towns and cities.

Exercise sucks

The reason why exercising helps bad air to hurt you is simple: when you’re exercising, you breathe in more of it. Up to 15 times more. “As well as sucking in a significantly greater volume, you’re also sucking it in much deeper, so it has a greater chance of getting absorbed,” says Mandy Dryer, a respiratory physiotherapist at the Manchester Royal Infirmary. “By just stepping out the door, you could be exposing yourself to five times more pollution, so if you’re outside and you’re exercising, you’re getting double doses.”

And that’s not all. According to Dryer, during my cycle I’m also bypassing my body’s remarkably effective air-filtering system: the nasal passages. (Mucus traps particulates, and then tiny, waving, hairlike structures called cilia push the old mucus up and out of the body.) The triple whammy of breathing fast, deeply, and through the mouth makes my daily commute an ozone/particulate/carbon monoxide orgy.

Eventually, our bodies defend themselves by breathing less. Air passages tighten and breathing becomes laboured. Our exercising bodies are ensnared in an intractable dilemma: while working furiously to process more air to feed oxygen-hungry muscles, they simultaneously strive to protect us from that air. Our pulmonary and cardiovascular systems strain like air conditioners in an extended heatwave and eventually, inevitably, can cope no longer and break down.

Early symptoms often include wheezing, coughing, scratchy throat, headache, chest pains and watery eyes. Other, longer-term effects are considerably worse. In Glasgow, researchers studied 30 healthy men on exercise bikes while exposed to diluted diesel fumes. After 60 minutes’ exposure, they developed constricted blood vessels and showed a reduction in tPA, an enzyme that breaks down blood clots in the heart. In another study, 17 competitive cyclists were exposed to varying levels of ozone while exercising; their endurance decreased by about 30 per cent, and their lung function by 22 percent.

Perhaps most disturbing is how airborne toxins can harm us without triggering symptoms. In the smog-bucket of Los Angeles, Berkeley University researchers examined 107 fatal cycling accident victims, ranging in age from 14 to 25. Before their deaths, none reported breathing problems. Yet autopsies revealed that 27 of the deceased had chronic lung disease.

The message to cardio devotees: easy breathing can confer a false sense of security. “Healthy, active people tend to underestimate the harmful effects of polluted air, because they don’t wheeze or experience chest pain,” says Dryer. “Experiencing no symptoms of anything wrong, they continue to exercise, putting themselves at greater risk.”

Airs and traces

To understand the kind and quantity of pollutants I’ve been inhaling over years of unintentional abuse, I went to an air-monitoring station in the centre of Bristol, overseen by Steve Crawshaw, the city’s air quality co-ordinator. Crawshaw, who’s been rigorously analysing air quality data for over 10 years, takes me on a tour around the Smeaton Road station, a stone’s throw from my gym.

He shows me the array of flashing terminals receiving real-time data from 10 permanent road-side stations and 130 temporary diffusion tubes around the city, used to monitor the high nitrogen dioxide levels that have forced parts of Bristol to become an ‘Air Quality Management Area’. It’s an overcast day with a prevailing southwesterly wind coming in over the River Avon, resulting in favourable air-pollution readings. But, when there’s high pressure and a light wind from the east, pollutants settle in the bowl of the city centre – the epicentre of my cycle route. “It really does change day to day,” says Crawshaw.

Diesel emissions have attracted particular attention in recent years, with the number of diesel-engine cars in the UK increasing more than threefold since the mid-1990s. A team from Edinburgh’s Queen’s Medical Institute recently identified tiny soot particles from diesel exhausts as the chief culprits in 9000 fatal heart attacks in the UK each year. The study showed how the particles cross from the lungs into the bloodstream, where they cause arteries to harden and clots to form, effects normally seen in heavy smokers.

“They’re so small they pass quite easily through face masks that people often wear to protect themselves,” explains Professor Ken Donaldson, a toxicologist who helped lead the research team. “One of the dangers with diesel particulates is that they adsorb other pollutants and interact with them inside the body,” he says. “They might prove to be closely linked to a variety of cancers. We’re just beginning to understand the threat.”

Dr David Newby, the lead cardiologist on the project, explains that compared to other risk factors such as cholesterol, high blood pressure and smoking, the role these particles play is less important, but on top of these other things it can be significant. “The difference is that the whole population is exposed to them unlike these other factors that affect individuals,” he says. “Air pollution affects everybody.”

Scientists are also now recognising that most air pollutants can only be meaningfully measured on a localised basis. An area downwind from a motorway, for instance, might have dramatically dirtier air than someplace upwind. Yet if the downwind area is factored in with more favourably positioned areas, the overall measurements might indicate that the city has healthy air.

Keep on riding

Faced with all this data, should we all quit our two-wheel habit? Despite the darkening diesel cloud, spiking asthma rates and proliferation of heart-stopping studies, all the experts assure me that, on balance, cyclists are doing themselves more good than harm. “I, for one, am going to keep cycling my regular three-and-a-half miles each way into work every day,” says Crawshaw, “but I am aware of when and where I cycle.”

He suggests changing my daily gym trip to early in the morning, when diesel particulates, ozone and other air pollutants are at their lowest levels, or after nightfall, when traffic abates. Ozone forms when sunlight reacts with traffic and industrial emissions, so it accumulates to significant levels by about 11am and peaks at around 3pm. “Try to avoid main roads wherever possible, especially where there’s often backed-up traffic,” he advises.

In general, every 50 metres you move away from a busy road, the pollution levels halve, so find routes through parks or on quiet back-streets if possible. “The worst time is on cold, still, clear winter days when pollution doesn’t disperse. Knowing how your local area reacts to pollution according to weather conditions is key.”

The National Heart Forum backs up Crawshaw’s view, citing evidence from the Netherlands that regular cyclists enjoy a fitness level equal to that of someone 10 years younger, while the British Medical Association estimates that cycling at least 20 miles a week reduces the rider’s risk of heart disease to half that of a non-cyclist. And, of course, it’s a good way of losing weight – using up at least 300 calories an hour.

Driving cars could offer the worst of all worlds: no cardio benefits and sucking in air through ventilation systems at ground level, where most pollutants settle, straight into your face. Dr John Moore-Gillon, who’s been looking at the damage caused to our lungs by pollution for the past 30 years, says: “There’s no doubt in my mind that if you exercise outdoors and take the relevant precautions you’re doing yourself far more good than harm – you just have to be aware of the risks to limit the damage.”

What are we inhaling?

Ozone (O3)

What it is: A toxic, unstable gas formed when a ‘freed’ oxygen atom combines with an oxygen molecule – known in pollution speak as ‘smog’. This reaction occurs when sunlight hits nitrogen oxide gases (NOx) and volatile organic compounds (VOCs) from vehicle and industrial emissions. High levels of ozone often form on clear, still, sunny days.

What it does: Toxic in very low concentrations, ozone can cause anything from shortness of breath to permanent lung damage. There’s also evidence that ozone increases the hazards associated with exposure to other environmental pollutants and allergens, making people more susceptible to infection and decreasing their ability to expel inhaled particles.

Nitrogen Oxides

What they are: Nitrogen compounds including nitrogen dioxide and nitric oxide that play an important role in the atmospheric reactions that create ground-level smog, or ozone. NOx forms when fuels are burned at high temperatures, the two major emissions sources being road vehicles and stationary combustion sources such as electric utility and industrial boilers.

What it does: At elevated levels, NOx can impair lung function, irritate the respiratory system and, at very high levels, make breathing difficult. When combined with other gases, it can pose even greater danger. As well as helping form smog, NOx also reacts with other compounds to form PM10s (tiny particles of smoke – see below for more), with the associated health risks.

Carbon monoxide (CO)

What it is: A colourless, odourless and tasteless gas that’s lighter than air. It’s created from the incomplete combustion of petrol and diesel – normally harmless carbon dioxide (CO2) is produced, but without the presence of adequate oxygen, carbon monoxide forms instead.

What it does: CO binds very easily to haemoglobin in red blood cells, responsible for carrying oxygen around the body. Because it binds to haemoglobin more easily than oxygen, it displaces the oxygen molecules, leading to suffocation of the cells. Symptoms range from headaches and nausea to severe confusion, but often people won’t know they’ve been affected until it’s too late.

PM10s

What they are: Tiny particles of smoke suspended in air, no bigger than 1/50 the size of the fullstop at the end of this sentence. Created by the combustion of petrol and diesel, they’re invisible to the naked eye, but you can certainly smell and taste them.

What they do: PM10s get lodged in respiratory passages and cannot be readily expelled from the lungs. While this has mainly a ‘nuisance effect’ in healthy people, for asthmatics, allergy sufferers and people with respiratory and cardiovascular diseases they’re potentially fatal. The latest Commons report by the environment audit committee estimates people with asthma could be dying up to nine years early because of PM10s.

Sulphur dioxide (SO2)

What it is: A colourless, non-flammable gas with a strong odour. The most common source of sulphur dioxide is fossil fuel combustion – coal burning is the single largest manmade source of S02, accounting for about 50 per cent of annual global emissions

What it does: As well as irritating the eyes and nasal passageways, it causes breathing difficulties, bronchitis, pneumonia and lung cancer. The Great Smog of London in 1952 led to around 4,000 premature deaths through heart disease and bronchitis. Tightness in the chest and coughing occur at high levels, and lung function of asthmatics may be impaired to the extent that medical help is required. S02 is considered more harmful when particulate and other pollution concentrations are also high.

Damage limitation

Here are some ways to limit your exposure to air pollution:

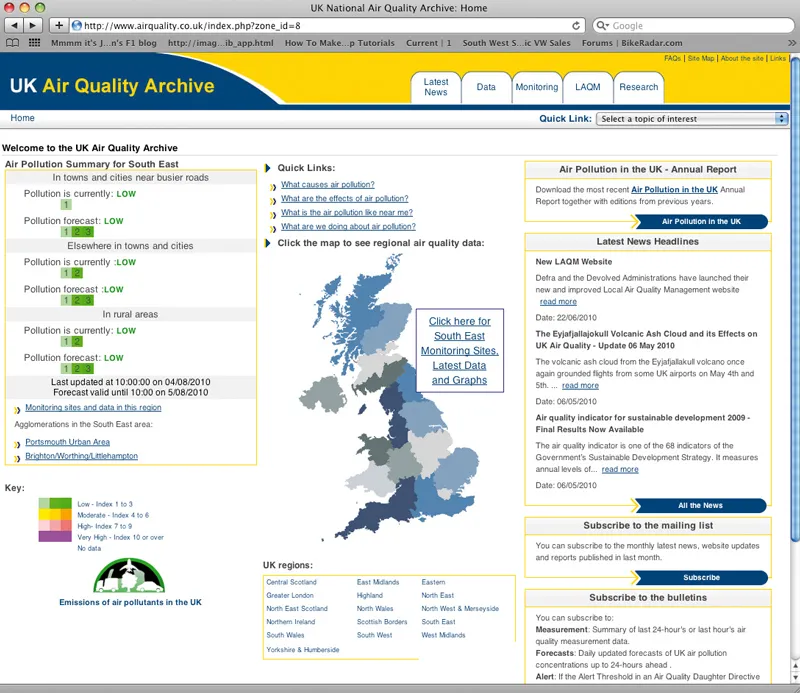

1 Log on: Almost every large city publishes detailed data on pollution levels on its website which, along with up-to-the-minute information from www.airquality.co.uk, means you can find out when and where it’s safest to venture out. “It’s often the same areas, in dips or close to busy and congested roads, that are worst, so by checking the data over a couple of weeks you can easily build up a good idea of where and when you should be travelling,” says Crawshaw. “Consider delaying your ride if the air pollution level is above 6 for any one pollutant.”

2 Lead the pack: Push your way to the front at traffic lights and busy intersections. “Most pollutants will come directly out of the exhaust and can even linger where jams regularly form,” Crawshaw explains. If that double-decker’s blocked your escape route, dismount and walk round to the front. And use the 10,000-mile network of traffic-free paths set up by Sustrans.

3 Get your vitamins: Fruit and vegetables high in vitamin C, such as peaches and red peppers, stimulate production of glutathione, a liver enzyme that helps prevent free-radical damage in the lungs. Just a few places down the antioxidant alphabet is vitamin E, found in nuts and dairy produce, which can also help repel radicals.

4 Take cover: Choose your weapon – aka mask – wisely. “They’re better than nothing, but they’re hard to breathe through during vigorous exercise,” says Dryer. “All too often the seal around your mouth and nose isn’t air-tight, so you end up sucking in unfiltered air through a gap and don’t push yourself as hard, so you don’t get the fitness benefits of cycling.”

Of the masks recently analysed in a joint Sustrans-BLF study, wraparound bandanas like Respro’s Bandit Mask (£18.99) produced the most effective seal, with a larger, machine-washable charcoal filter to strip out most PM10s and noxious gases. In fact, Respro are the only brand to have the official endorsement of the BLF. “Of course, holding your breath, or at least going into a thin, shallow style of breathing when in stationary traffic should help any mask to cope better with the demands you make on it,” adds Dryer.

5 Home grown repairs: You can’t control the air quality outside, but within the confines of your own bricks and mortar, an areca palm (around £9.99 from garden centres) is the best houseplant for removing air toxins, according to Dryer. “It’s easy to care for, thrives indoors and releases large amounts of water vapour into the air, which gives your lungs a better chance to recover from whatever you’ve taken in outside.”