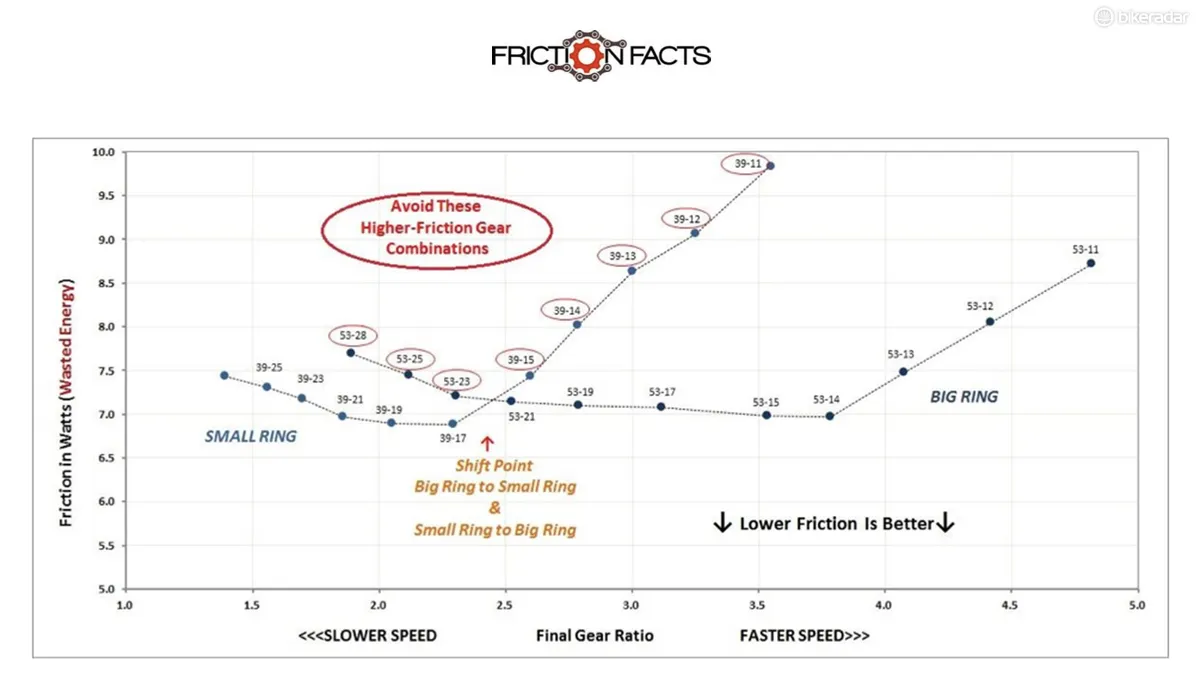

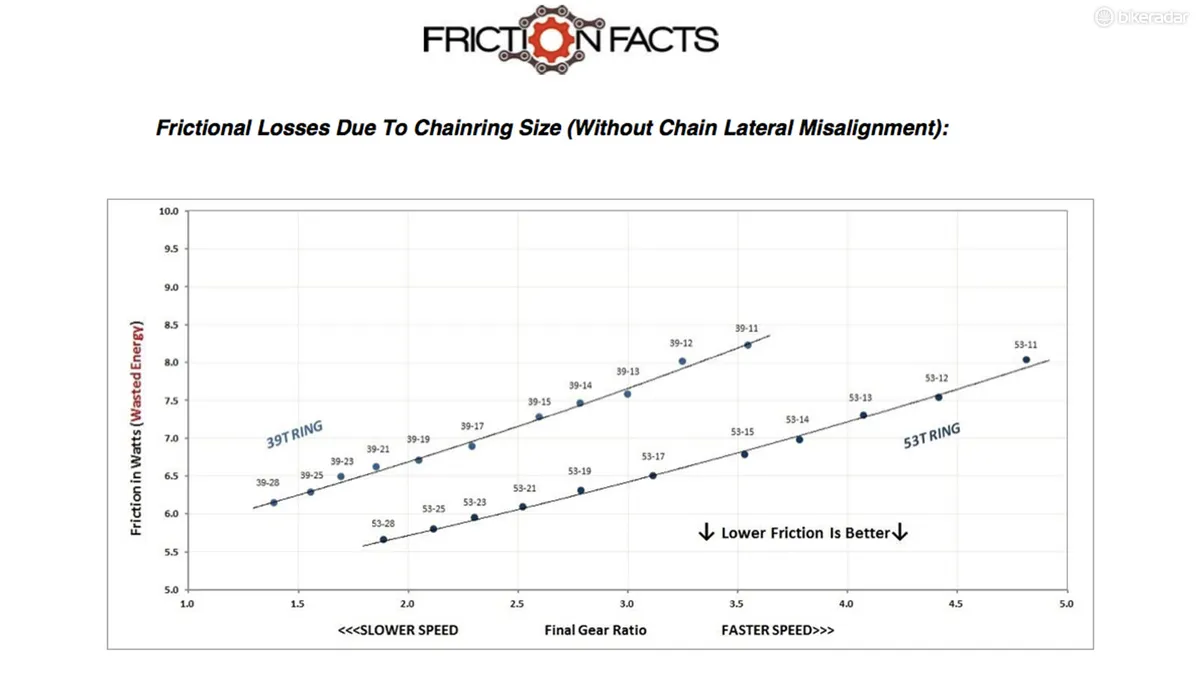

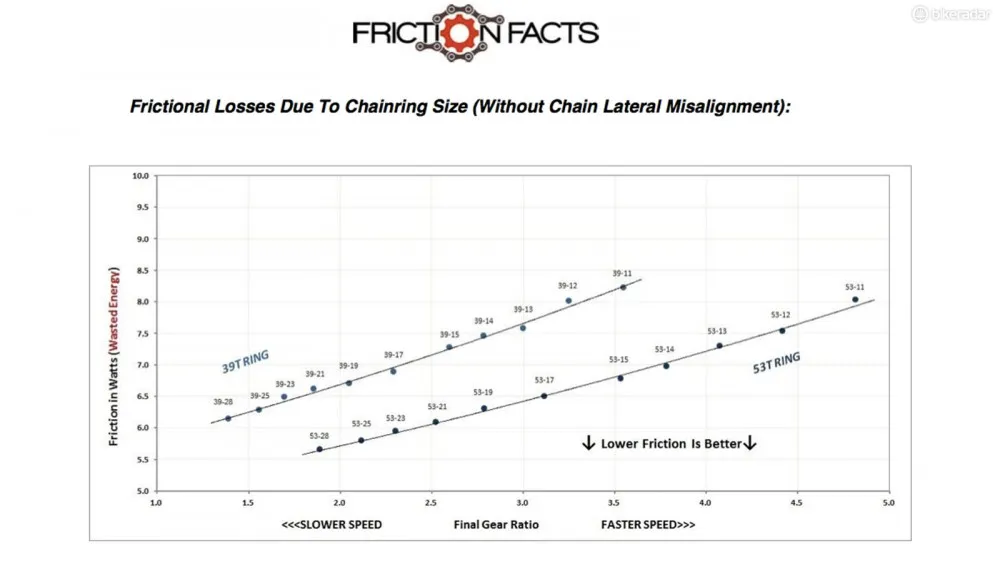

The folks at Friction Facts are at it again, this time investigating how gear selection affects drivetrain drag. Just as racers have been saying for ages, Friction Facts has now proven that it’s more efficient to stay in the big ring, saving nearly three watts of effort in certain combinations – but there is a tipping point where it’s still better to drop down up front.

Friction Facts’ earlier study on rear derailleur pulley size suggested that larger-diameter chainrings and cogs would produce less friction than smaller ones, and this latest exercise confirms that hypothesis. Despite the fact that bigger chainrings and cogs create higher chain speed (which slightly increases friction), Friction Facts says the lower chain tension and reduced individual chain link rotation more than offset lower frictional losses overall.

Generally speaking, bigger chainrings and cassette cogs produce less friction than smaller ones for an equivalent gear ratio

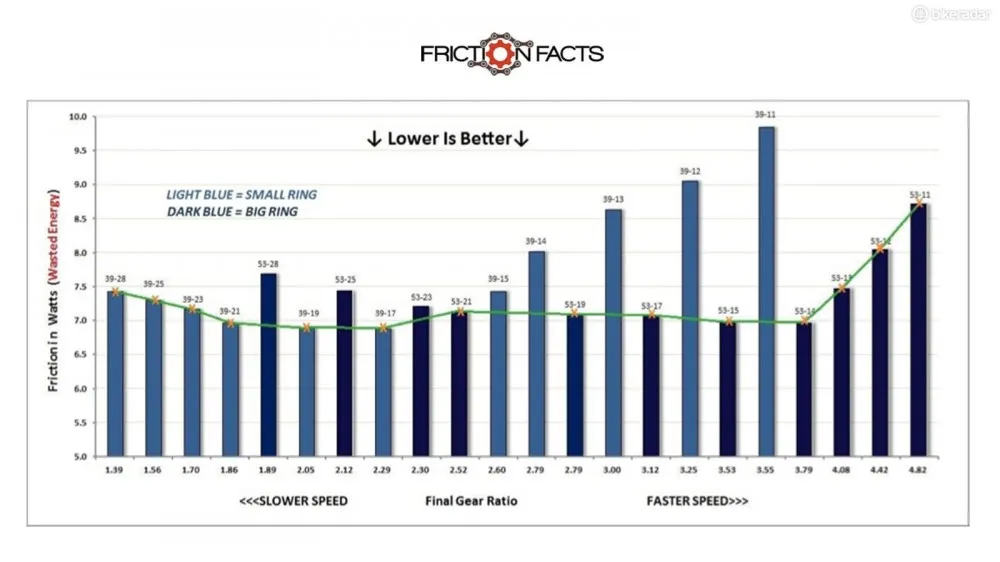

A 53-15t combination, for example, yields almost the exact same gear ratio as a 39-11t but the latter requires an extra 1.5w to maintain the same speed – and that’s in a lab setting where the chainline can be perfectly aligned.

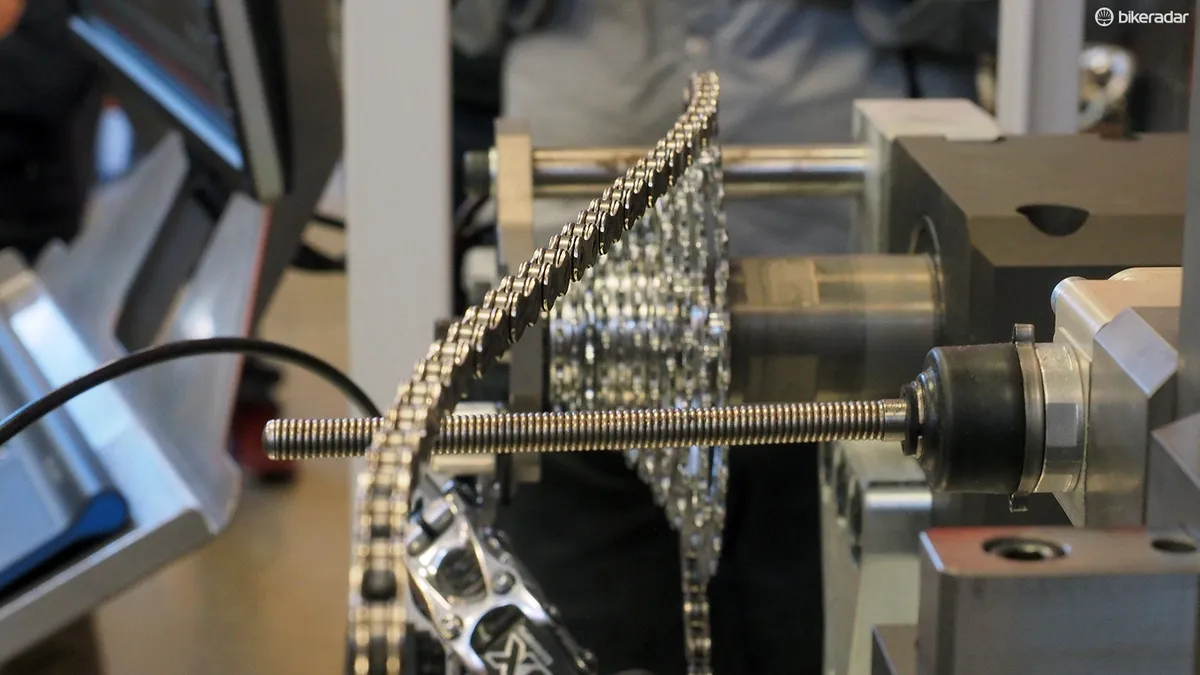

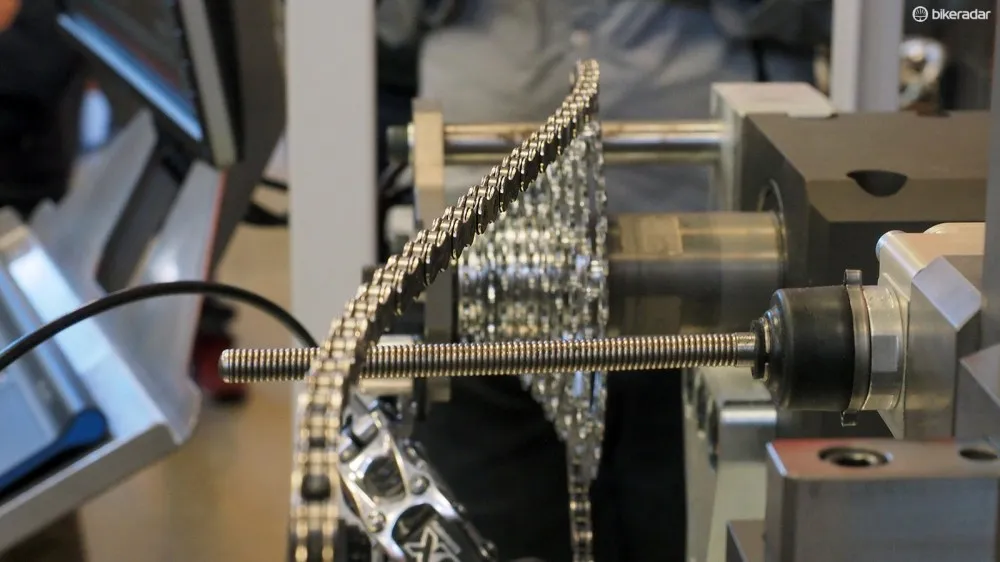

Things get even more interesting – and the potential energy savings double – when accounting for chain angle on a real-world drivetrain.

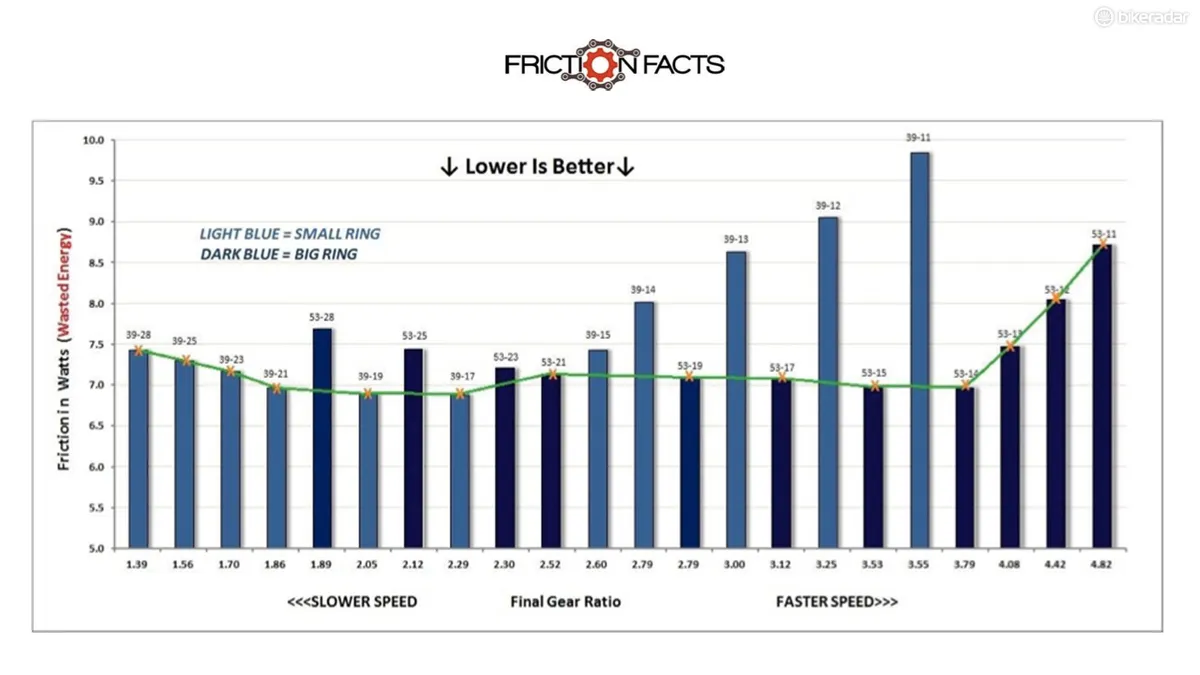

Racers invariably love the big-big gear combination but it turns out to not be very good in terms of frictional losses

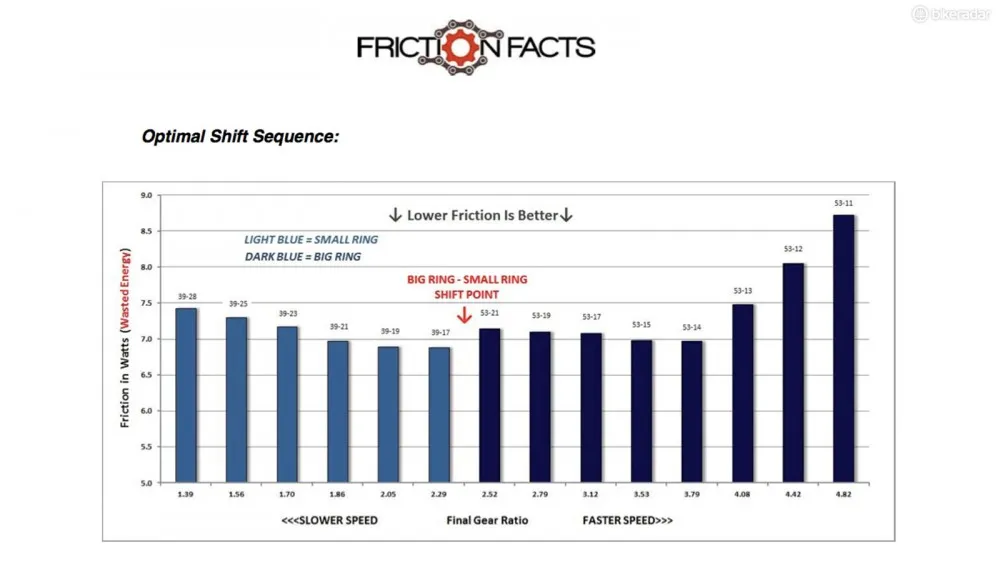

In general, Friction Facts says it’s better to stay in the big chainring for maximum drivetrain efficiency – but not all the way to the biggest (easiest to pedal) cassette cog out back. More extreme lateral chain angles will eventually tip the scales in favor of the inner chainring – and not just at the most extreme big chainring-big cassette cog combination that most people think of when considering ‘cross-chaining’.

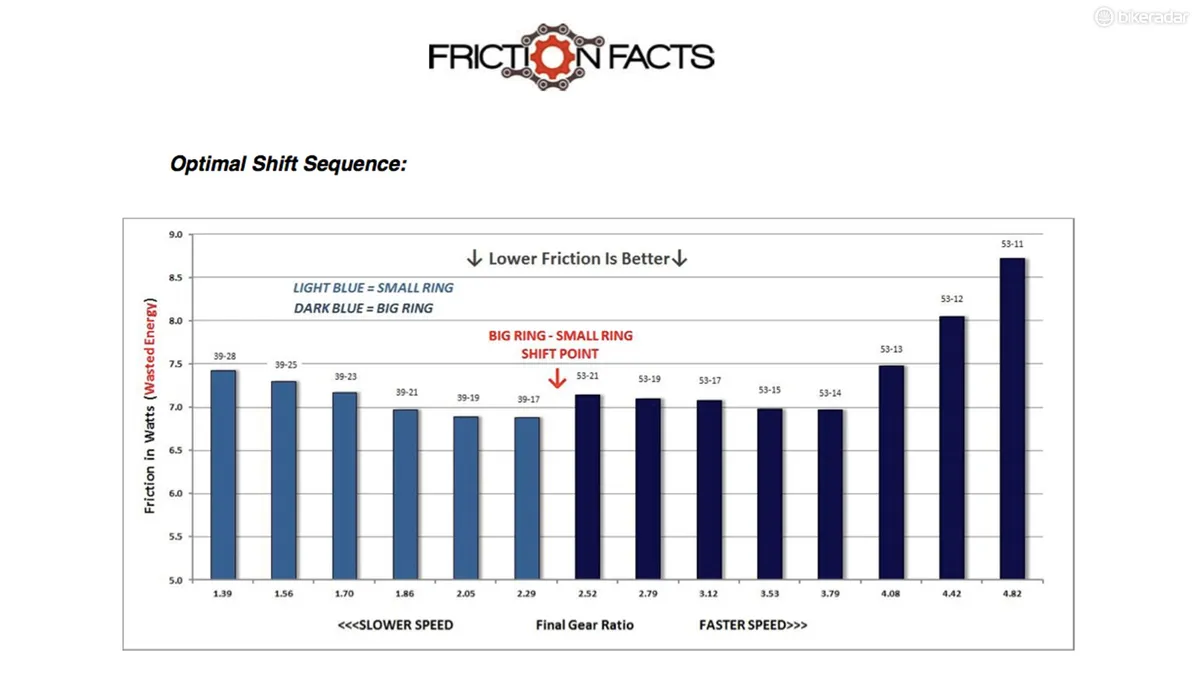

According to Friction Facts, the tipping point comes eight cogs in from the outermost cassette position – roughly two-thirds of the way across. On a modern drivetrain with 53/39t chainrings and an 11-28t 11-speed cassette, this means that if you’re in the 53-21t and need an easier gear, it’s better to drop down to the inner chainring and select the 39-17t combination instead of using the 53-23t one.

According to Friction Facts, there exists an optimal shift point for dual-chainring drivetrains in terms of minimizing drag

If you instead insist on staying in the big ring all the way up to the 28t cassette cog – thus putting the chain at an extreme angle – you might think that you’re going faster but you’re actually pushing about 0.75w more than necessary had you instead shifted to the 39-21t.

At the other end of the spectrum, it’s quite common to see cyclists using the opposite cross-chain combination, the 39-11t. Given that extreme lateral angle produced, the smaller cogs, and the faster chain speed, Friction Facts says this rider would be pushing nearly 3w harder than if they were using the nearly equivalent 53-15t pairing instead.

Shift smarter, go (a little bit) faster

Riders hypersensitive to these so-called ‘marginal gains’ will likely want to keep Friction Facts’ latest study in mind – every watt counts, after all. Carrying the topic even further, time trial racers and triathlons might even consider optimizing their chainring and cassette combinations so as to produce the lowest drag possible (barring subsequent increases in weight and/or aerodynamic drag, that is).

“The important takeaway,” says Friction Facts founder Jason Smith, “[is that] it's not good to ride the big ring-big cog combination, but it's much worse to ride the small ring-small cog combination.”

For more information (and the complete in-depth cross-chaining study), visit www.friction-facts.com.